Glawe: From across the aisle: Obamacare debate reflects GOP’s efforts from 1990s

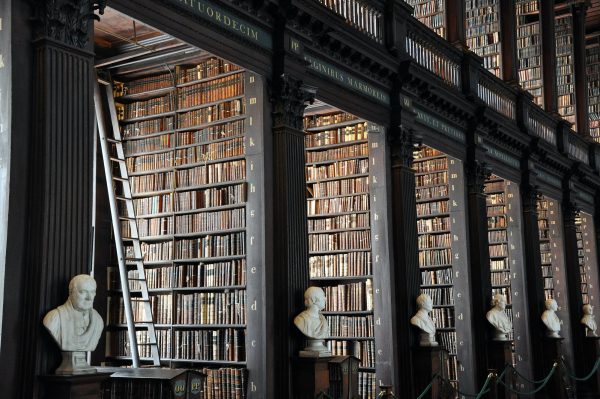

Leah Stasieluk/Iowa State Daily

Democrats and Republicans still cannot make a final decision on health care.

October 15, 2013

It was 1993, and the country was embroiled in a tumultuous health care reform debate concerning various proposals by both the Clinton administration and Republicans alike. Robert Dole, then-Senate minority leader and presidential hopeful, along with 23 other Republican senators, co-sponsored a bill introduced by Sen. John Chafee.

In an attempt to provide universal coverage while still creating a counter-balance to President Bill Clinton’s plan, the proposal, among other things, included a mandate that individuals purchase health care insurance. In addition, the bill required insurers to provide “standard benefits” packages and to eliminate discrimination based on pre-existing conditions.

“Hillarycare,” as the former was dubbed, failed miserably without firm backing from the Democratic Party, which was hampered by fractured alternative plans. The Republicans backed off their proposal after routing the opposition in the 1994 elections. However, there was, as there always is, a surreptitious reason for the failure of our efforts to reform health care.

In a strategy memo addressed to Republican politicians, William Kristol argued against any reform for fear that Republicans would never again claim the gavel of the House. As he put it: “On the grounds of national policy alone, the plan should not be amended; it should be erased completely.”

Kristol recognized the political threat posed by a compromise with Clinton’s plan, therefore “it would be a pity if the advancement of otherwise-worthy Republican proposals gave unintended support to the Democrats’ sky-is-falling rationale.”

The hope for health care reform was killed.

This strategy remarkably foreshadowed the coming zero-sum politics of the late 1990s and 2000s. It has become commonplace for constituents to gripe and groan about the failure of compromise in Congress in its present nature. Neglected are the background actors of the Grover Norquist-sort (similar to Kristol) whose ideologies, prejudices and craving for power too often stymie the political process.

The underlying character of our current affairs is, to evoke Theodore Draper, a Machiavellian “struggle for power.” Under this context, as Sheldon Wolin put it, “the wholly good man and wholly evil one are rendered superfluous.” Kristol’s role in eliminating the Chafee bill makes him partly the latter.

Ironically, it is the basic elements of the Chafee bill that have been the target of current Republican scrutiny. The resistance to the Affordable Care Act, which hinges on the mandates, represents yet another episode of the shifting political tides. The question is begged: Who now plays the role of Kristol? Not a single individual, but many.

The GOP of today is nearly engulfed by the “no compromise” strategy, at times betraying their traditional positions. The Democratic Party is not blameless either, as the partisan divide is widened everyday.

The rhetoric, too, has changed. Politicians to the extremes of either side no longer say they oppose just certain provisions of an opposition’s bill; they instead oppose the bill outright.

But this nonetheless reiterates the point — the condition of power requires a contrast of “them vs. us.”

It is not too difficult to notice the pandering, either. For instance, both presidents Ronald Reagan and George Bush used stimulus policies to revive the economy. Yet, when President Barack Obama issues a stimulus package, GOP leaders cry havoc and let slip the dogs of war. The same can be said, in a relative way, of the Affordable Care Act, of which Democrat’s would say inches uncomfortably close to Republican policies (a market-oriented approach).

Noting the hypocrisy is of course nothing new, but it nevertheless underscores the ongoing struggle to paint the other side as the villain. This is the rawness of politics — the dirty play that came to define Machiavelli’s work.

Under the guise of political rallies and pseudo-events at the World War II memorial, the House Republicans again stand poised as Machiavellian actors attempting to usurp power — or perhaps take advantage of it. Recklessly utilizing the dual threats of a debt default and the government shutdown, the GOP has adopted the “evil” means to the ends. They certainly recognize, as did Kristol, the political threat posed by the Affordable Care Act, and they intend to stamp it out.

Going back further, moderate Republicans embraced the tea party influx of 2010 as a means by which they could overthrow the Democratic majority. In an effort to retain power and win the voters, the party had to differentiate itself from Obama and abandon some of its own positions, even at the expense of the well being of Americans (embracing austerity, the 2011 debt ceiling crisis, the “Sequester”, etc.). As a result, the moderates no longer control their own party.

What we now face are politicians on both sides of the aisle willing to block and repeal anything they don’t like, and patiently wait until the next election cycle affords them the opportunity to again seize power.

Perhaps Dole’s reflection on the early 1990s provides an anecdote: “You give up some things and you get some things. If you get 70 percent, that’s OK. You don’t just put a big ‘No’ sign on your desk.”