Gross: Are video games ‘art’?

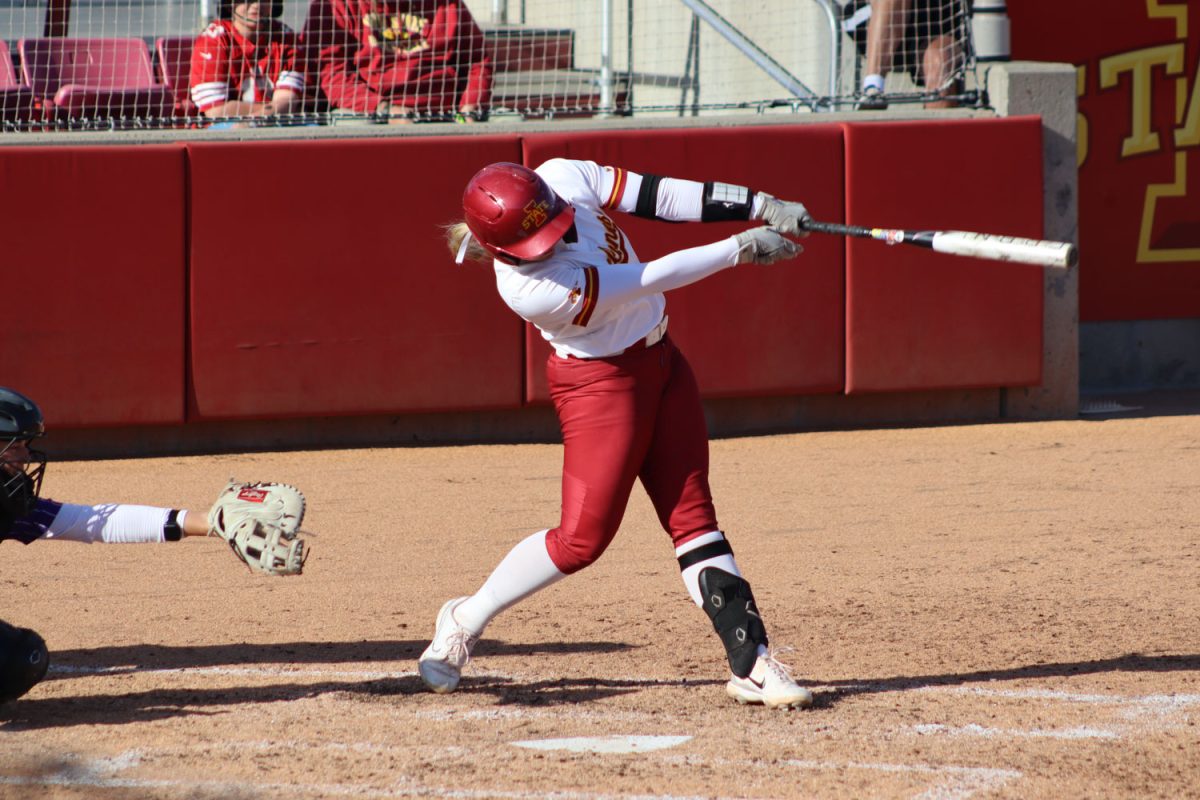

Kelby Wingert/Iowa State Daily

Can video games be considered an art form?

September 5, 2013

The Eiffel Tower. An 8-year-old’s finger painting. “Mona Lisa.” A hastily scribed poem. Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5. “Bioshock Infinite.” Which of these are art, and which are not?

Traditionally, art has encompassed paintings, music, sculpture and literature. In more modern times, film and animation have been added to the list. But another form of entertainment and expression has arisen and remains uncategorized: video games.

Video games are ridiculed by many as the stuff of children, a pastime that should die with a teenager’s fading acne. Despite that reputation, gaming is a form of entertainment that thrives across many age groups. But are they the cultured expressions of creativity that we general accept as “art?”

As in any medium of expression, the answer is, sometimes. Each painter and sculptor looks upon various works with a different eye. To some, a work might be a masterpiece; to others, trash. Movie critics praise works of particular beauty but denounce directors or actors who accept “paycheck roles” as opposed to more cultured work.

Similarly, it can be argued that some video games, created for the beauty of animation, storyline or soundtrack are artistic works while others are not.

Although we categorize many modern games as creative art, it has not always been so. Many would say modern role-playing games, played on a top-of-the-line gaming PC, fit the ticket of creative expression; few would say the same of 8-bit games of the 1980s.

In video games’ beginning, from the simplistic “Pong” to classic arcade games such as “Pac-Man,” technology wasn’t advanced enough to push games into the visual category of “art.” On top of being visually clunky, soundtracks and effects were chirpy and cartoonish. As exciting as these blocky, pixelated games were at the time, they didn’t compare to other art media: fine arts such as paintings, animated or live-action movies or highbrow literature. The technology just couldn’t keep up.

In the current decade, technology is at the point where the graphic quality of some games successfully mimics reality. Additionally, the music that accompanies gameplay is fluid and beautiful, more comparable to movie soundtracks than the screechy sounds of yesteryear. Each year, we see new game releases that inspire awe with the complexity of their graphics, storylines or soundtracks.

However, just because technology is at a point where it can come close to if not exceed the beauty of “real life,” that doesn’t mean that “art” is the intent of all games.

Online flash games and games made specifically for smartphones or tablets (think “Angry Birds”) hardly classify as art. Gameplay complexity is minimal; plot is usually nonexistent; graphical quality is only as high as it needs to be for the casual player to be entertained.

That isn’t to say that there is something inherently wrong with “Temple Run” or “Fruit Ninja.” Their main purpose is to entertain during short periods of time, and they do it well.

Other games, though larger in scale and with bigger budgets, could be argued are made solely for entertainment. Popular first-person shooters such as the “Battlefield” or “Call of Duty” lines both have much more enticing sound and visual effects than does “Angry Birds,” but they still fall far from what people would call “art.”

First-person shooter games have storylines and single-person gameplay that many enjoy, but with generally predictable plotlines and a gameplay focused on online player-versus-player competition, these games are more of an outlet for competitive spirit than they are a model of culture or emotional expression.

These “blockbuster” games are no less an example of the industry’s success than are more artistic creations, they simply entertain a different audience. Video games are similar to the movie industry: Some productions are made for the consumers of cultured, high-brow film where other, equally large-budget works are made for entertaining the masses.

Traditionally in the last decade, games that many would say fit the bill for being works of art are those within the genres of “sandbox” or role-playing games. These large-scale games are as much about the experience and atmosphere as they are about the end goal. For example, a gamer could spend 100 in-game hours on Bethesda’s “Skyrim” (2011) without even touching the main quest line. For games such as these, the world in which one plays is so vast that visual and auditory details are extremely important.

Though role-playing games maintain their status as works of creative expression, another genre is making headway in that arena: indie games. Games produced by individual developers are more often considered “art” because it is the designer’s personal dream or brain child that directs the form and function of the game.

Indie games such as “Dear Esther” are almost entirely atmosphere with very little action or gameplay; game completion feels more like having completed an emotional journey than having “beat the game.” “The Dream Machine,” a game made entirely by hand out of clay and cardboard, is an example of visual art merging with technology to create a stunning experience.

Whether made by a team of 10 or 100, a game is only as much as it is intended to be. If it is lovingly created with the intent to be played as a work of art, then it may be regarded as such. In past eras of gaming, creating games as a form of visual, storytelling or auditory art simply wasn’t possible. In today’s time, not only is it possible, it’s become a profitable arm of the gaming industry.