Barley genome gives insight into future pest and disease resistance

November 5, 2012

After decades of hard work, the barley genome, or genetic code, has been cracked.

The barley genome is twice the size of our own human genome and was successfully ordered and assembled by an international group of scientists ranging from many different scientific disciplines.

The International Barley Sequencing Consortium is the group of scientist who cracked the genetic code of the 5.3 billion lettered barley genome, and the research was published in the most recent edition of “Nature.”

This consortium was created in 2006 and is a collaboration of scientists from 22 different organizations in nine different countries.

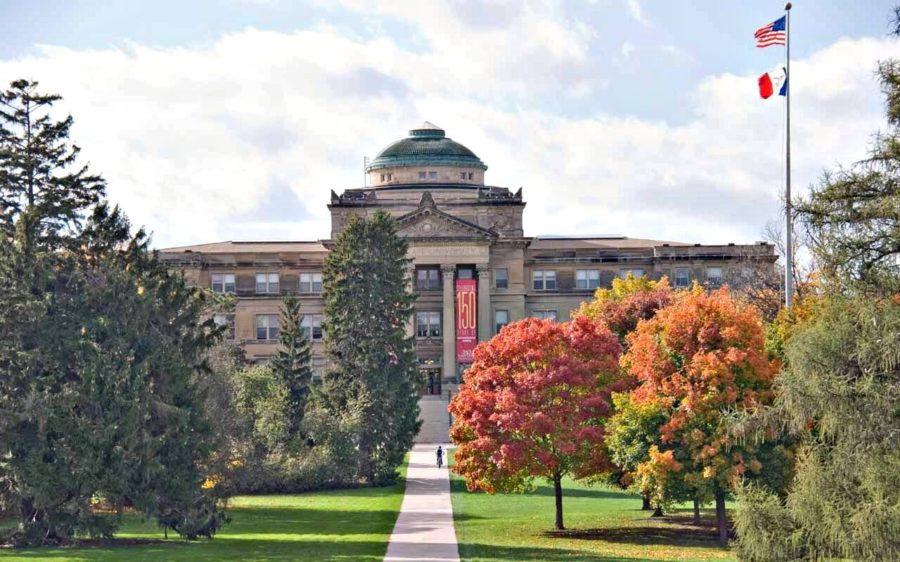

Roger Wise, research plant geneticist for United States Department of Agriculture-Agricultural Research Service and collaborator professor of plant pathology at Iowa State was one of these scientists.

“This project was absolutely huge, and this is reflected by the well over 60 authors on the paper,” Wise said.

Records indicate that barley has been around and developing for more than 10,000 years, originating in modern-day Middle East.

Today, barley ranks fourth among the cereals in worldwide production, behind wheat, rice and corn.

According to the National Barely Growers Association, 320 million bushels of barley were produced each year in the United States from 1994 till 2003, averaging $760 million dollars in the agricultural economy.

This research is the first of many steps to bring an increase in yields, improve pest and disease resistance, and enhance nutritional value to barley.

For Wise, his research will help his lab at Iowa State to investigate traits that in-teract, are present and/or play a role in disease resistance.

“The thing about plants is they can’t go anywhere from their diseases; they just sit there and take it,” Wise said. “In my lab we will try to figure out how the plants determine to become resistant to that disease.”

Wise’s lab is made up of technicians, post-doctoral, graduate and undergraduate students.

Five graduate students majoring in computer science, statistics, plant pathology and biophysics played huge role in this research. Two post-doctoral members and one undergraduate, studying genetics, also assisted Wise.

“Everyone in the consortium has their own teams back in their own countries, much like mine,” Wise said.

Wise said computer science and statistic students helped his lab to become more efficient with gathering information regarding the genome and working on different locations on the large Barley genome.

David Acker, associate dean of global agricultureprograms in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, said undergraduates students working in research laboratories is common at Iowa State, but not in many other universities across the nation.

“Mentor relationships much like this are vital for students to decide if this is the career path they want to pursue and gives them hands on experiences that maybe a lecture cannot provide,” Acker said.

By cracking the genome to barley researchers are able to gain insights in ways to develop barley so that they are more resistance to disease and pests.