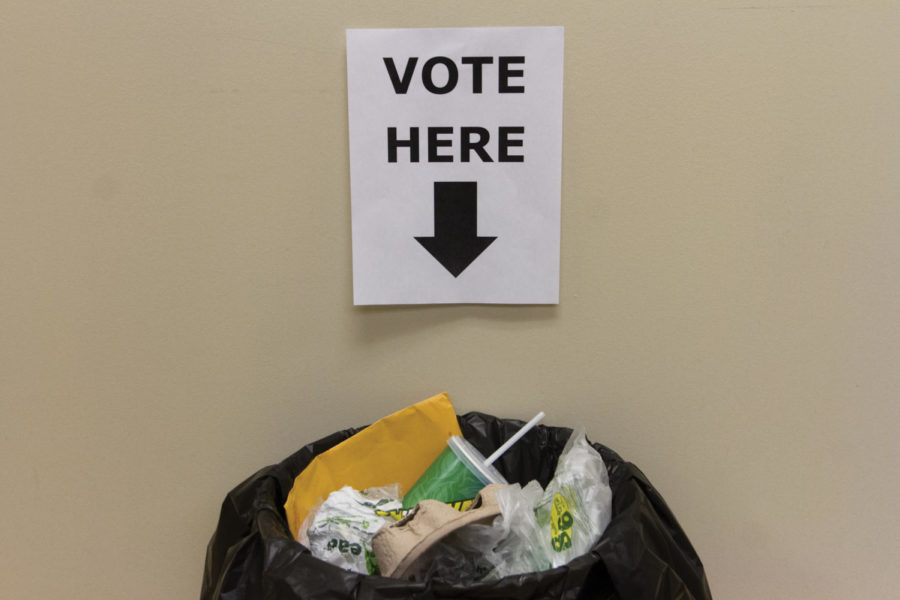

Belding: Disinterest in election shows sameness of parties

Photo: Megan Wolff/Iowa State Daily

Opinion: Belding 9/25

September 25, 2012

Regularly, I check for interesting reads at The New York Times website (among others), including their opinion section. Back in July, I found one piece that got me thinking: It was a dialogue entitled “Caring About Politics” by David Brooks and Gail Collins. The exchange focused on voter apathy.

Right off the bat, Brooks cited recent polls: “Not a lot of people are following politics closely this year. Four years ago, pollsters asked Americans if they found the presidential race interesting. A clear plurality said yes. This year, a clear plurality says no. Somehow they find a race between two androids less than scintillating.”

My curiosity piqued, I poked around on the Internet and found a few Gallup polls on voter enthusiasm and voter intentions.

Among Democrats and voters who lean Democratic, only 39 percent of voters are more enthusiastic than usual about this year’s election. That compares to 61 percent four years ago in 2008, and 68 percent in 2000.

Republicans aren’t much better: 51 percent of Republicans and Republican-leaning voters are more enthusiastic than usual to vote come November (compared to 35 percent in 2008 and 51 percent in 2000).

Especially dismal is the reckoning for Americans ages 18-29 years old. In 2008, 69 percent of them said they were definitely likely to vote. In 2004, that number was 61 percent. But this year in June, only 58 percent said they would definitely vote.

Estimates for the causes of such disinterest in the future political leadership of the United States range from distress about our societal minds turning to mush and being too absorbed in the fabricated cyberworld (a la “turn on, tune in, drop out”) to the toxic partisan litmus testing so popular among Republicans these days. With such strict dress code requirements, who would want to even knock on the door of that party?

I think it’s something different that’s pushing Americans away from anticipating the election with bated breath.

I think this year — our options being Barack Obama and Mitt Romney — the lack of enthusiasm for the election (to say nothing of the candidates themselves) in the wake of Tea Party liberalism finally shows how equally committed both parties are to private rather than public life.

Rather than using public policy to shape the way in which we interact and to keep private and public lives in their proper, separate places, American politics is obsessed with the material benefit of people in their individual lives. Little attention goes toward the Constitution’s commission of forming “a more perfect union.”

Nearly all the dialogue, at least on the level of the presidential candidates, is about bettering the private lives of Americans, such as putting them back to work and letting them keep more of their paychecks. We would all exist with or without the United States.

To be inspired about politics or public life we need to be interested in actions that make people want to say “I’m proud to be an American because my people have done X, Y and Z” rather than “I’m proud to be an American because my president isn’t a closet Muslim and my taxes are the lowest in the world.” Any government can enforce law and order and collect high or low taxes. What sets America apart? What gives us the exceptionalism that so many politicians, right and left, point to on Independence Day?

One of our founding fathers and most ardent and forceful of the Constitution’s defenders — its writer, James Madison — wrote that “If men were angels, no government would be necessary.” Here is a sorry truth: Men are not angels, and government is necessary. Madison preceded that comment with a rhetorical question: “But what is government itself but the greatest of all reflections on human nature?” Men are neither inherently good nor inherently rational as liberalism from Hobbes and Locke to the present day has claimed.

Living in complete isolation from one another, they might be capable of living without conflict but, where two or more people are gathered, government is necessary. Their conduct must have limits other than the sky. Rules of the game must be established.

And the game’s players must understand that the game and its rules are more important than themselves — for without the game and its rules, they would, at best, fail to leave any lasting impression on the world and would, at worst, devour one another.

“All the world’s a stage,” Shakespeare wrote. “And all the men and women merely” — think about that: merely — “players.” Sportsmanship is about upholding a standard of play — an ethic — not the aggrandizing of oneself.

Politics is a sport of its own. It is a game that should be played for its own sake, not for any of the players.