Belding: Constitutional agreement necessary before political action can begin

Photo courtesy of Flickr/Brett Whaley

Opinion: Belding 9/11

September 11, 2012

Britons and other citizens of monarchies proclaim the words: “The king is dead. Long live the king,” whenever a reigning monarch dies, in order to deny the possibility of an interregnum, a period of time in which no man was king, and immediately acknowledge a successor in office.

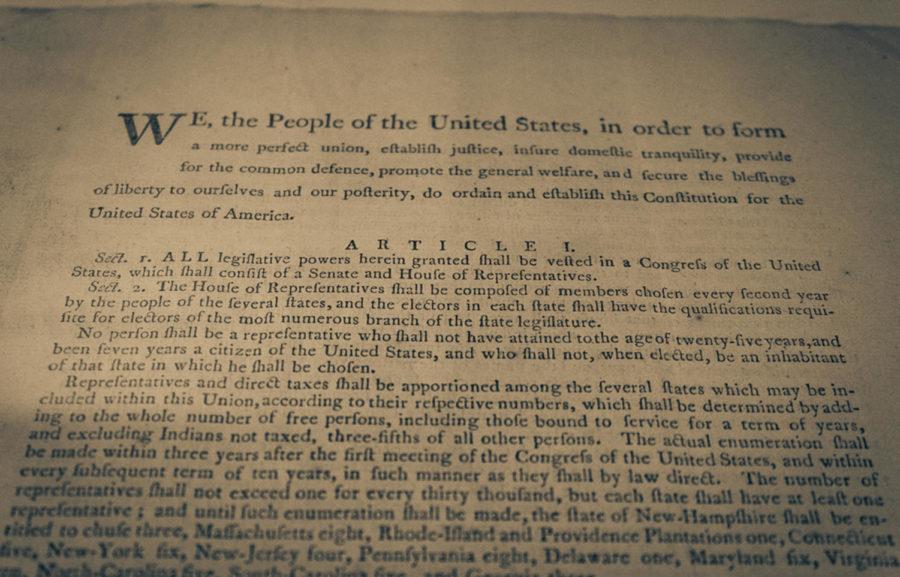

Every election cycle, we Americans could, with justification, say: “America is dead. Long live America.” In our system, the Constitution is King and the president, justices of the Supreme Court and senators and representatives we elect are his agents. Yet, despite being the essence of our political union, the Constitution’s meaning is elusive.

We — Democrats, Republicans, conservatives, liberals, moderates — cannot, for the life of us, agree on what the Constitution means. Americans are impossibly divided about how the Constitution should be interpreted. According to a Washington Post-Kaiser Family Foundation-Harvard University “Role of Government Survey” published in October 2010, 50 percent of Americans believe the Supreme Court should base its interpretations of the Constitution on what it meant as originally written. A nearly equal number, 46 percent, take the opposite view, that the Constitution should be interpreted according to what it means in current times.

That result is not new. According to the same poll, the numbers for 2005 were simply reversed: 46 percent of Americans were originalists and 50 percent believe in the Constitution’s adaptability.

A political typology survey done by the Pew Research Center the next year, 2011, found a similar divide over the Constitution’s interpretation. That June, 45 percent of Americans thought the Supreme Court should “base its rulings on what the Constitution meant as originally written,” and 50 percent thought it should “base its rulings on what the Constitution means in current times.”

Those data also show clearly the partisan nature of the disagreement: 70 percent of Republicans are on the side of what the Constitution meant in 1787, and 65 percent of Democrats favored interpretations based on the present.

That nearly-even split among Americans at large and the partisan split between Democrats and Republicans show the unlikelihood of developing a consensus on what should be an easily-comprehensible document. It is short; we all learn about it all through school; the legal, political, and historical disciplines are devoted to its study; it is invoked at every turn; and the marketplace of books is awash in anthologies of speeches, letters and pamphlets created by the delegates to the Constitutional Convention.

Alexander Hamilton explained in the 78th installment of “The Federalist”: “A constitution is … a fundamental law.” He continued his thought a few essays later, in No. 81: “The Constitution ought to be the standard of construction for the laws, and that wherever there is an evident opposition, the laws ought to give place to the Constitution.” In other words, the Constitution is an essential prerequisite, a sine qua non, to the laws we enact through our political process, without which the latter could not exist. But without agreement on the rules of the game, the players can neither take the field nor begin playing.

Nationwide unemployment was at 8.3 percent in July. To bring that number down, we should lower tax rates for the wealthy (job-creators) or the government needs to run a deficit in order to pay for programs that put people to work. In 2010, 15.1 percent of Americans lived in poverty. To decrease that rate, we must increase state support for charities, lower taxes on corporations and wealthy Americans so that better-paying jobs that were outsourced can return to the United States or be started from scratch, invest in education or reform welfare.

Also in 2010, 49.9 million Americans (16.3 percent) went without health insurance. To cover more of them, we either need to maintain government support for such programs and mandates or allow the free market to run its course. With some 11.5 million illegal immigrants (or “unauthorized immigrants”) in the United States in 2011, clearly we need some kind of border control, guest worker program or more fundamental change in immigration policy.

Demand for educated workers is supposed to reach new heights; by 2018, an estimated 29.5 million jobs will open up in the United States that will require at least some college education. That demand is anticipated to exceed the supply. To make up the difference, the government should invest in higher education (by such measures as low-interest student loans, direct funding to colleges and universities and grants to students with financial need) or allow new private for-profit institutions of higher education to fill in the gap.

Those are just a few of the issues that figure highly in public discourse. There are others. What each of them shares in common is that no action on any of them can occur until members of Congress and the whole U.S. population decide to agree — either by resigning and giving in, or by hashing out the debate in an intelligent way — on the basic premises of the Constitution.

Monday, Sept. 17, will be Constitution Day. The delegates to the Constitutional Convention signed their names to the Constitution nearly 225 years ago. Now is as good at time as any to rescue the political system they confidently established.