Belding: Politicians need willingness to debate, to enact whatever solutions are feasible

April 19, 2012

Politics, I think, are pretty fun. Too often, however, politics are confused with government, a completely separate concept. Politics happen whenever two or more people get together to have a discussion or do something together. Put simply, politics are out having a good time. They require interaction with other people and being out in the world. Politics require exposure to forces outside one’s own mind.

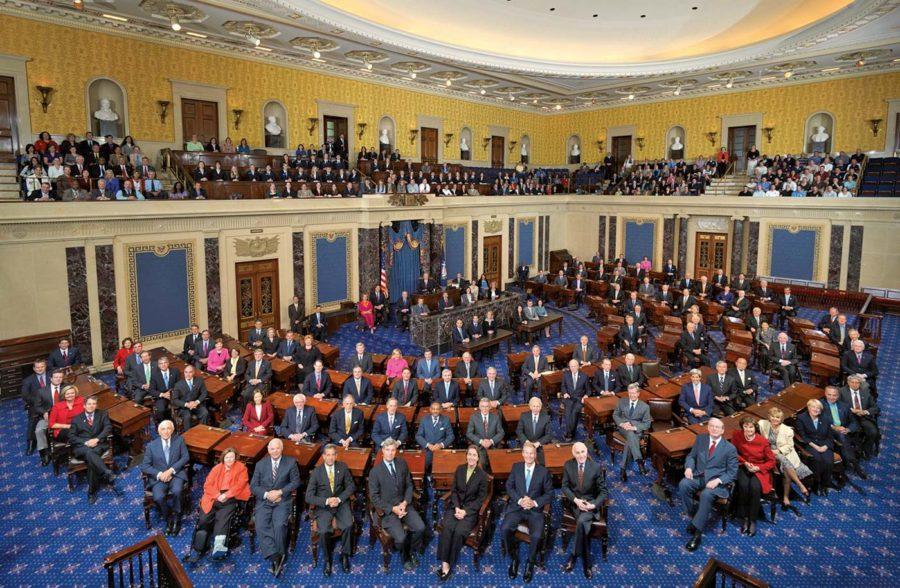

Modern American politicians, however, seem to disagree. They show no desire to debate one another, ask questions or give answers. Especially in the Senate, where members go for five years without having to campaign for another term in office, politicians should be waiting with bated breath for every chance to prove their political skill and show themselves to the world.

Instead, we see farces like we did on Monday, when a cloture motion failed in the Senate. That motion would have allowed debate to begin on a bill that, if passed and signed by President Barack Obama, would have enacted what is called the Buffett Rule — in the case of this particular version, a minimum 30 percent tax on people earning more than $1 million annually from any source of income.

And while debate preceded the vote to open debate on the Buffett Rule, that vote’s failure meant there was no opportunity to actually debate the Buffett Rule itself.

Of the 45 Republicans voting on the motion, 44 voted to keep the Buffett Rule from consideration. Another part of politics is acting as an individual, not as a group. Senators especially are insulated by the Constitution from having to play the reelection game and curry favor with average voters. Their six-year terms and, as the Constitution was originally written, election by state legislatures mean that senators are elected by state politicians who are also supposed to have political skill, with the result that senators will have genuine political skill even as they have plenty of time to further cultivate their political talents.

Refusing to debate a bill that, according to a CNN poll, 72 percent of Americans favor and 53 percent of Republicans favor, is political cowardice. Refusing to allow an open debate on the Buffett Rule represents an unwillingness to work within the political process. The statements Majority Leader Harry Reid, D-Nev., and Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., made about the cloture vote are revelatory. Both phrased their remarks with respect to larger issues of the American economy and Obama’s policy preferences rather than framing their comments with respect to the senators who would actually have had to vote on the bill.

Instead of doing real politics by working with their colleagues, it seems that both would rather use their offices to garner attention for their party’s ideology. The whole point of a senate is that its members will bring their state’s perspective to politics, not some nation-wide overarching philosophy dictated by a political party with its own ideological intentions. I doubt very much that all 45 opposing Republicans did so because their state perspective encouraged them the Buffett Rule is bad policy, especially since the only Republican to join the Democrats, Susan Collins of Maine, is widely known as a moderate centrist.

The comments around the failed cloture motion suggest the senators are more interested in show — or gamesmanship — than fixing problems. It is much more likely that they opposed debating the bill simply because their Republican ideology and opposition to the president dictated otherwise, than it is that they actually care about considering potential solutions to seemingly insurmountable budgetary hurdles.

McConnell may be right in saying the Buffett Rule may represent a very small part of a solution to our gargantuan fiscal problems (after all, if implemented, it would bring in only $47 billion over 10 years), but that reasoning fails to consider the quantity of good legislation that has been passed as packages of smaller bills.

Probably the best example of passing comprehensive bills in bits and pieces is the Compromise of 1850. That September, Sen. Stephen Douglas and Sen. Henry Clay, members of two different political parties, worked together to pass a set of measures that would keep the United States together in the years leading up to the Civil War. The problem of legislators’ opposition to bills because of one small portion of them is not new.

Recognizing this problem, Douglas divided the bill into five separate bills. Altogether, they fixed the Texas border; admitted California as a free state as it was; banned the slave trade in Washington, D.C.; passed the Fugitive Slave Act; and allowed popular sovereignty on the slavery issue in the territories of Utah and New Mexico.

Great solutions to great problems are often passed piecemeal. We need to stop believing that big problems can be resolved only by big solutions and that proposals inadequate by themselves should be shunned. If we need to put our fiscal house in order, then we need to go line by line through the budget, look for feasible cuts and revenue sources, and enact those cuts and revenue sources — such as the Buffett Rule — where it is possible to do so.

Politicians often compare the U.S. Treasury to a family bank account. When they are faced with money problems, households everywhere make budgets and closely examine their spending habits. Maybe, instead of invoking families as tools of rhetoric, senators should apply the real lessons they offer: When a helpful action is possible, it should be done, whether it solves the whole problem in one stroke or not.