Belding: Having a personal life provides solid foundation for social life

Columnist Belding says to separate your public from your private life to keep your ideas fresh and your opinions new.

February 27, 2012

Some of my fellow columnists lament the lack of anything exhilarating, such as the 1960s space program and the race to the moon, in modern politics. Often it seems as that we have no lofty unifying purpose. There needs to be something about which we can get excited.

I know a few things about the exhilarating. My mom got her pilot’s license when I was in seventh grade, so I have been exposed to the exhilarating thrill some people have with that kind of thing. Having flown myself, I can recall the floating sensation that happens when an airplane’s wheels leave the ground and you’re airborne.

But what I want to say, instead of “oh, we’re doing nothing inspiring, and how awful that is,” is this: “We need to take a break from the inspiring every now and then instead of cheapening something good by indulging in it all the time.”

For instance, Vanilla Coke is good stuff, and I drink it all the time. One recent Sunday, I ran out and didn’t stock up again until Thursday. Most of the time when I go without it for less than 96 hours, I’m cranky with a headache and ready to kill someone. Since I did not feel any of that this time around, though, I held off. When I finally did crack one open on Thursday, its deliciousness was unparalleled.

We debase the good things in our lives by doing them too often. To prevent from debasing things like politics, corrupting them with our own personal passions and our own petty interests, we need to take time away from the world at large and cultivate our own tastes, talents and perspectives.

There is a time and purpose to everything. It is easy to get lost in the world, to lose touch with one’s roots.

I went out to dinner last week with one of my columnist-friends, and we got to talking about what we wanted to do for careers. I want to teach and to earn a Ph.D. in history; while it would be great to do so at a famous university with world-renowned faculty, I would not mind returning to Iowa State to teach, either. In fact, it is my preferred choice. Central Iowa is my home. I would love to improve it. Iowa has a state song, you know. It begins like this: “You asked what land I love the best, Iowa, ’tis Iowa / The fairest State of all the west, Iowa, O! Iowa.” I am inclined to agree.

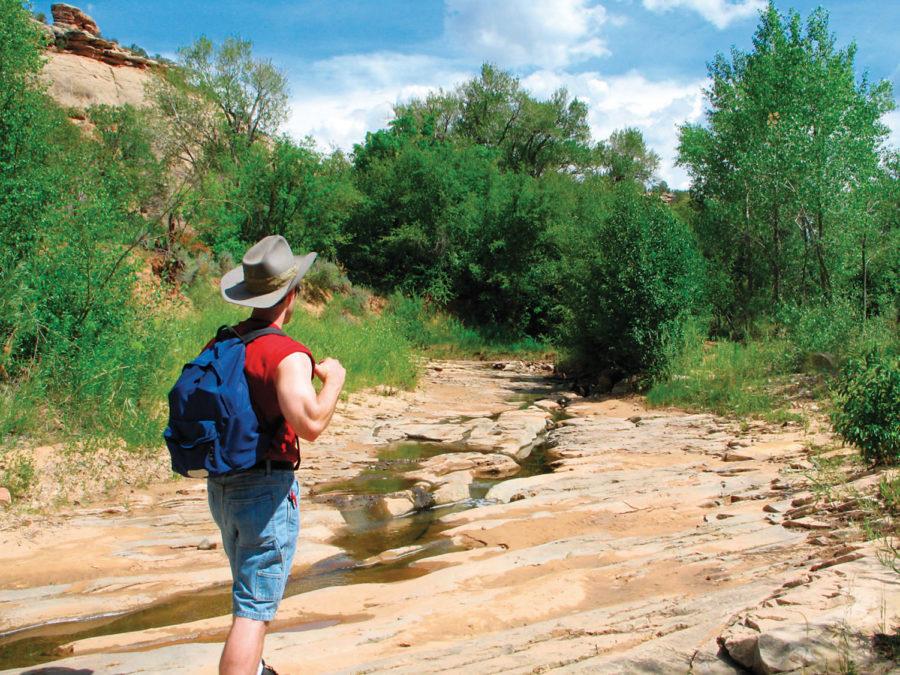

We need our own unique places in the world on which to fall back so we can collect ourselves, regroup and gear up for the fight ahead — and so we can keep whatever part of our sanity remains. An oasis or paradise in the desert that is the public and social world is essential.

One of the most common criticisms of politicians is their private lives are a mess. That should be enough to convince you that having a private world of one’s own — in which I do not include things like television, Facebook, Twitter and texting or instant messaging several people at the same time, what I understand to be the “room of one’s own” sense about which Virginia Woolf wrote — is a prerequisite to entry into public view. Some of the strongest criticism of Newt Gingrich, to name just one recipient of it, has been based on his much-married, tumultuous romantic past.

“The only man never to be redeemed is the man without passion,” the libertarian heroine Ayn Rand wrote. She was right. Even the greatest public figures must maintain their own private lives. As Winston Churchill put it, every public man has a little black dog of depression who follows him. Churchill’s remedy was to spend time painting and rebuilding the gardens at his home, Chartwell.

Thomas Jefferson’s solution was constantly to invent new devices, to read — “I cannot live without books,” he said — and collect more and more information about the world, pushing the limits of our knowledge. The Lewis and Clark expedition was as much about finding and cataloging new specimens of plant and animal as it was about mapping out the Louisiana Purchase.

Less is more, the saying goes, and the answer to our broken politics — or broken anything — might be less of it. If we all cultivated or own tastes and passions and brought those perspectives into our interactions, rather than relying on the stale repetitions of previous encounters, maybe the world would be a better place. At the very least, it would not be a broken record. Would that really be so bad? I ask myself that question just as much as I ask you.