Peterson: Education needs to continue beyond classroom

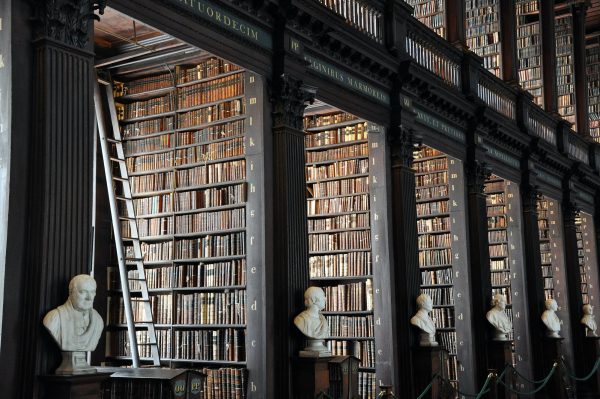

Illustration: Jordan Melcher/Iowa State Daily

University Universe

February 7, 2012

Volatility defined my first year at Iowa State. Not only had I transferred into school late, but I was coming from the Citadel Military Academy. I was insecure, but my old high school friends on campus helped integrate me into my new environment.

In the new college environment, my old hometown friends were recognizable. Most had declared engineering majors by the time I transferred, and although I wanted to declare political science, I was around engineers most of the time. As a result, I found myself continually hanging around engineers, studying with them and seeking their advice on homework and academic decisions.

I consider myself lucky to have engineering friends. Their influence is one of the best things that could have happened to me at Iowa State. Even though I was studying political science, my friends were — and still are — engineers. They taught me to see the world through a different lens, one I might otherwise have missed without their influence.

Even now we continue to debate over political, historical and philosophical issues. As engineers and social scientists, our interaction helps each of us see the world in a new light. For me, their empirical insights helped put political questions in more definite material dimensions.

The interaction between our disciplines required a mutual respect. My friends and I know each other and respect each other, but it could have been just as easy to immerse myself among friends of my own beliefs.

If I hadn’t intermingled with other majors, I would have lost the potential benefits they offered me. The respect for their study, the new information about their discipline and the challenges they have presented me have contributed more to my education than any class.

Over the years, I’ve come to see stereotypes accompanying each major. Political scientists are egotistical, historians live in musty collections, design students are ditzy and engineers are antisocial nerds.

As political scientists, we debate over which issue is most important: public policy, international relations, theory, American politics or law? Engineers divided themselves between aerospace, materials, electrical and many others. Philosophers divide between epidemiologists, logicians and metaphysics. Every study is divided into specific niches.

When I imagine my own discipline, I cannot help but deconstruct the others. I am forced to exclude the virtues of other methods, without even knowing what it is the other departments do. I negate them and define my position as different from them. I am fairly confident there is an injurious rivalry between majors. It’s unfortunate; by developing more cross-education among disciplines, we could advance our own studies.

The insight into the methods of engineering students helped make me more analytical, and I know the discipline of design could have made me more spatial and symbolic in my thinking. History has trained me to think in “rational” terms, pursing historical facts and links to create the most valid inferences on the past. Art would have trained me to see more dimensions to historical issues; perhaps I have missed important links between historic facts due to my lack of symbolic reasoning.

I know many students who entered the social sciences to avoid math and physics. However, natural science can benefit the social sciences. Engineering insights made it easier for me to read analytically, process precise laws and issues in legal courses and find important historical proof in piles of information.

I find myself using the methods of philosophy and math together in order to solve political questions of game theory, political poling and political speculation. I’ve concluded that our studies are not as narrowly tailored and separate from one another as we make them. In fact, I think they interlock. An engineer may not need political science, but interaction with his or her peers is unavoidable.

He or she will have to negotiate and debate in a world of literature majors and design students who think in their own respective ways. The ability to share insights into the methods of one another will not only help the engineer express his or her ideas but discover new potentials in engineering.

I think education requires a diversity of studies, and diversity can come from friends as well as classes. Political science is just an example. I depend on the events of history to explain the present, and I use statistics as an ever-increasing influence in political models. Even seemingly distant subjects such as physics and philosophy share a common link.

The classical philosophy of Thales, Aristotle and Plato was largely a matter of physical questions concerning the world, and even today it is hard to study the physical world without considering what we ought to do with the knowledge or what experiments are ethically sound.

Without my friends, I would have missed an entirely different world. As a student, I didn’t have time to take engineering courses or learn advanced math, but I didn’t need to. Education is not restricted to the classroom. The friends we associate with and the private activities we pursue often teach us more than what we learn in class.