Snell: Consider what it means to be a veteran

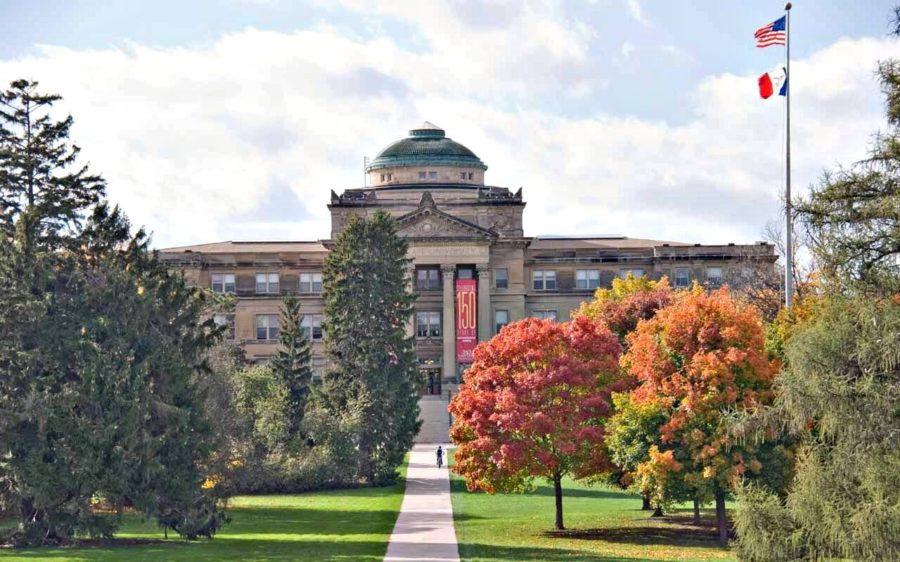

Photo: Kelsey Kremer/Iowa State Daily

Air Force ROTC honor guard member, Cody Beemer, sophomore in civil engineering, stands at attention next to a display for national POW/MIA recognition day Friday, Sept. 17 in the Gold Star Hall in the Memorial Union. The empty table is set to recognize prisoners of war and those missing in action.

November 11, 2011

Today is Veteran’s Day.

Much ado about the meaning of today will be made, and for good reason. But what we hear often, we begin to take for granted and eventually ignore. Such seems to be the case with Veteran’s Day, Memorial Day or any other holiday for that matter.

Politicians and famous people trot out all the old speeches, repeating the same inspirational quotes and the same words others have said a thousand times before until the whole thing becomes a cliche. I know just writing about the merit of Veteran’s Day is in itself cliche, but hopefully this will serve to inspire you to think about it in a new way by considering what exactly it means to be a veteran.

The word “veteran” itself means someone who has a great deal of experience with something or in a job. For purposes here, that means someone who has experience in the military and, quite often, in war. But that doesn’t tell the whole story either because being a veteran has a greater meaning than just being someone who joined the military.

A veteran is someone who had the intestinal fortitude to walk into a recruiter’s office and sign their life away to the service of their country. The politics behind America’s military actions are debatable and the reasons why a person joins the military are many, but the common thread is the sheer guts it takes to hand that blank check over to your government for the amount of, up to and including, the most valuable thing that person has: their very life.

What’s more, the amount of Americans willing to sign their lives over to their country increases dramatically during war time. When the risk is greatest, you’ll find your countrymen standing in a line to sign those papers and take their oaths.

Think about that. When the odds of getting killed or permanently crippled are the highest, your fellow citizens are more likely to join the military, regardless of that risk.

Many veterans will make light of the situation and joke that combat is the most exciting thing you can do with your clothes on. Others will rightly testify that it’s the most terrifying and horrifying thing you can do in any state of dress.

And while there is no possible way to explain what combat is like to someone who has never experienced it and never had their life directly threatened by another human being, those Americans who have been there can tell you that both the best and the worst of humanity is seen in war.

Watching the top of your friend’s head get removed by a piece of shrapnel from an exploding 88 round during The Bulge … holding your buddy in your arms while he slowly bleeds to death in the jungle outside Khe Sahn after he was shot half a dozen times by the Cong … or climbing up into your Humvee’s turret to man the 50 cal because your squadmate fell back inside, injured after an RPG exploded outside, only to reach up the grab the gun’s grips and instead grab his still attached hand.

Or it’s your head, your blood flowing into the grass or your hand blown off.

These are the stakes. Yet there are people willing to go do it and if asked, they’d go do it again in an instant. They experienced the most challenging situations beyond imagination and through it all cared for and loved each other in a way that literally makes them closer to each other than their own families.

They laid it all out for one another in their most vulnerable moments, living, loving, crying and dying together. It is a weird dichotomy, war. How can it be that such beauty exists — no, thrives — in the midst of such horror?

Millions of Americans that you don’t know and never will have agreed to risk going through this for you. Many of them came back home in a flag-covered box and some never came back at all. So what kind of person can love you so much that they would die for you without ever having met you?

Who can love their country so much that they would die for her and the principles she stands for? Who can take those risks and not expect any thanks in return, knowing that the thanks is, ironically, in having been one of the few to sign on the line and raise their right hand?

A veteran.

If the idea of that doesn’t stir your soul, nothing can. So if you see a veteran, shake their hand or maybe give them a hug. If you can’t think of anything to say, that’s OK. They’ll understand the message: Veterans, we love you.