International student learns job market’s unspoken code at Career Fair

Anniken Westad

Sarani Rangarajan, graduate in journalism, stands outside Hamilton Hall. She hopes to find an internship that will give her a chance to learn about workplace norms in the United States.

September 29, 2011

Sarani Rangarajan loves living in the United States. She’d love to work here, too. But before she can do that, she has to find someone to hire her.

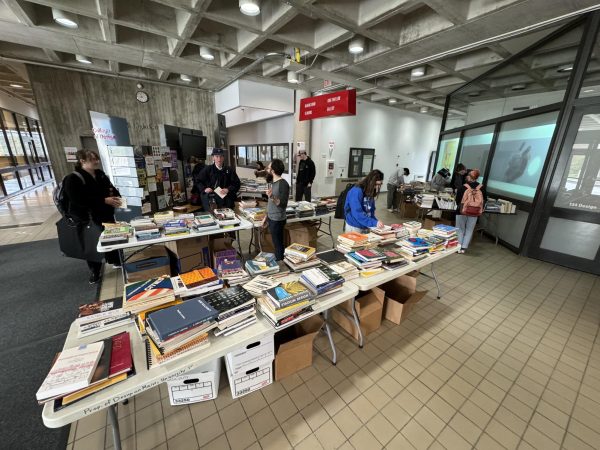

In hopes of finding that person, Rangarajan, graduate in journalism, set out for the ISU Career Fair, which was held in Hilton Coliseum on Wednesday.

As an Indian national who’s studied in America since 2008, she’s had time to observe the competitiveness of its job market. She’s also noticed the myriad workplace conventions Americans have to follow — conventions that, in some cases, have no Indian counterpart. Some of them still baffle her.

Approaching Hilton by bus, Rangarajan compared Indian and American styles of communication.

“We talk in a completely different way,” she said. “In India, if someone says ‘I think you should do x,‘ it means ‘Maybe you should do it.’ In the U.S., it just means ‘Do it.'”

Ascending the Hilton stairs, Rangarajan said she hadn’t mastered all the workplace behaviors successful Americans display and respond to. She hoped she would find an internship at the fair that would teach them to her.

“International students have to make an extra effort to understand social cues,” she said as she passed through the doors. “I couldn’t take a job without interning first.”

In the lobby, Rangarajan presented her student ID at a registration table. After being supplied with a name tag, she started toward the floor of the arena.

While walking, she said she wanted to cover science for a major U.S. newspaper, but understood how scarce jobs of that sort were. All too conscious of their scarcity, she’d decided not to hope for too much. At most, she expected to learn about public-relations jobs with a selection of her “must-hit” firms: Boston Scientific, CDS Global and Honeywell.

On the coliseum floor, she joined a current of formally dressed students flowing between rows of booths. She quickly escaped it and joined a line in front of the Mayo Clinic’s area.

She seemed surprised by how much one-on-one attention students were getting from the clinic’s representative.

“In India, you’d mob them,” she said with a smile. After a pause, she clarified that Indian students would probably be more self-conscious about taking up a professional’s time with individual questions, and would thus be more likely to speak to him or her in groups.

Watching the representative leaf through a brochure with a student, she seemed to grow nervous.

“I just think I’ll have much better luck online,” she said.

Minutes later, when she reached the Mayo booth, the woman at it said she wasn’t aware of internship openings for communications specialists, and directed her to the clinic’s website.

“I just don’t like hearing ‘no,'” she said as she left the booth behind.

Moving to the booth for Boston Scientific, Rangarajan introduced herself to the staff behind it and posed the same question she’d asked the Mayo rep moments ago.

She walked away a couple minutes later, smiling sardonically.

“I heard what I expected to hear,” she said. “Not a ‘no,’ but close.”

After a visit to CDS Global, a data-management company with corporate offices in Des Moines, Rangarajan tried to put herself in the place of American managers considering international employees.

“They’re concerned about extra work,” she said, mentioning that companies often had to engage high-priced lawyers to cut through immigration-law red tape. “And there’s this rush to buy American” she added, giving her impression of trends in the U.S. job market.

She interrupted her commentary mid-thought to question the appropriateness of the brown pantsuit she’d chosen to wear. Everyone else, she said, seemed to have chosen darker colors.

“It’s a bit odd being a brown suit in the midst of all these blacks,” she said.

En route to the Honeywell booth, she moved to other topics, marveling at the ambiguity of the signals she’d gotten.

“Some of these people say things and I don’t know if it’s positive or negative,” she said.

Honeywell’s was one of the last booths she’d planned to visit. But when she got close to it, two signs at its site discouraged her. Returning from the booth, she said there had been two notices posted that read “Citizens Only.” (According to an ISU Career Services web brief about Honeywell, applicants must have a U.S. citizen’s or permanent resident’s work authorization to be eligible for jobs.)

Rangarajan left the Career Fair with little more hope than she brought to it. Nonetheless, she was encouraged by her encounter with CDS staff. Not only did the company have an office close to Ames, it also seemed receptive to taking on students like her.

“CDS I will definitely apply to,” she said, paging through a PR booklet she’d taken. She noticed the word “globally” in a section on employee recruitment and gave a small laugh of relief.

“There are these little keywords they use,” she said. “If they mention them it’s good news for me.”

In an interview early Wednesday, Dilok Phanchantraurai, a program coordinator for the International Students and Scholar’s Office, said it was common for job-seeking international students to have doubts like the ones Rangarajan expressed.

“The main challenge that our students have is finding an employer who’s willing to keep the student, or sponsor the student to stay here longer on work visa,” Phanchantraurai said.

He added that he’d noticed fewer international students looking for jobs in the U.S. and greater numbers of them looking for jobs in their home country.

“In the past — let’s say about four or five years ago — almost every single one would say ‘I want to get some kind of work experience in the U.S.’ That is not the case anymore,” he said. “I think the trend is, because of the downturn in the job market in the U.S., fewer employers are willing to hire international students.”

Rangarajan hopes to defy the trend Phanchantraurai identifies. She knows that, eventually, her ability to do so will determine whether or not she has to leave the U.S.

“You can’t stay without a job,” she said.