DeVore: Remember origins of Labor Day, those who sacrificed

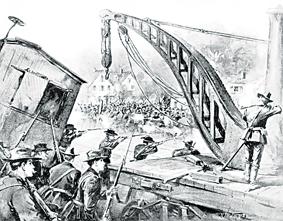

Photo courtesy Chicago Historica

Violence in Chicago escalated when federal troops came to break the 1894 Pullman factory strike, as illustrated in this drawing from Harper’s Weekly. More than 1,000 rail cars were destroyed, and 13 people were killed.

September 6, 2011

Each year Labor Day comes and goes without any consequence or intentional recognition. For many, Labor Day symbolizes the ceremonious exchange of white couture for a wardrobe laden with plaids and rustic fall colors. The holiday serves merely as a reminder, which prevents a most unfortunate fashion faux pas.

We as Americans have been acculturated in a climate of disconnect from the origins and roots of meaningful traditions like Labor Day. Admittedly, I have “observed” labor in ignorance my entire life, not realizing its deep-rooted history in American expansion. The evasive gap in time from the roots of Labor Day observance have ironically privileged the privileged of today’s society, not the intended “working man.”

The beginnings of Labor Day observances arose in the tail end of the 19th century with a man named Peter J. McGuire, who was a co-founder of The American Federation of Labor and also the secretary of the Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners. It was reported he was one of the first people who proposed a bill that honored, “who from rude nature have delved and carved all the grandeur we behold.” Tuesday, Sept. 5, 1882, was the first celebration of Labor Day. Held in New York City in accordance with the planning of the Central Labor Union, it marked the expansion of the public recognition of the working class as the “workingmen’s holiday” in America.

With the growth of labor organizations throughout America, it was celebrated in many industrial centers across the country by 1885. It was not until June 28, 1894, that Congress passed an act recognizing Labor Day as a national holiday on the first Monday of September each year. However this legislation was not as noble as one would think, it served as a political Band-Aid more than anything.

Arising for the drastic cuts in wages, the Pullman strike was a nationwide conflict between the labor unions and the railroad companies of America consisting of nearly 126,000 workers. After the rail companies began hiring replacement workers during lockouts, the labor unions grew angry and began rioting. Led by Eugene V. Debs, there were a reported 6,000 rail workers that participated in the uprising in Chicago. United States Marshals and some 12,000 United State Army troops were sent to break up the riots and killed 13 strikers and wounded 57.

The Pullman Strike of 1894 was the catalyzing force in passing the legislation. President Grover Cleveland wanted to appease the labor movement in fear of future civil unrest. After the riots, Debs was arrested and jailed. However, after his release in 1895, he became one of the leading socialist figures in America, running for president in 1900.

Now that we have a little more historical context through which we can reflect on the meaning of Labor Day, I can bet you are a little confused. America has tried so hard to leave us in the dark about the roots of Labor Day and its true meaning. Why are we not educated about the Pullman Strike and how labor unions played such a vital role?

It seems that political interests have played an active part of veiling the history. In my opinion, the people who currently benefit the most from Labor Day are the salaried employees who are integral parts of American bureaucracy — not the “workingmen” it was supposed to celebrate.

We as members of the educated and privileged elite have a paid holiday while hourly wageworkers are tied to their minimum wage jobs. A day’s wages for some is the difference of making ends meet or not. For them, Labor Day is an untouchable luxury that many will never enjoy. So what started as a positive practice for members of unions who worked hard labor has evolved into one that benefits some of the bureaucrats who rally against the “workingman’s” right to unionize. Ironic? Yes.

So in the future as you sit in your lawn chairs, grilling and drinking your beer, remember the holiday came with the price of blood. It was the blood of unionized workers that created a proletariat uprising, the blood of Marxists laborers who fought for their rights. That, my friends, is American. Viva la revalucíon.