A lesson in life: Entrepreneurial engineering professor puts students first

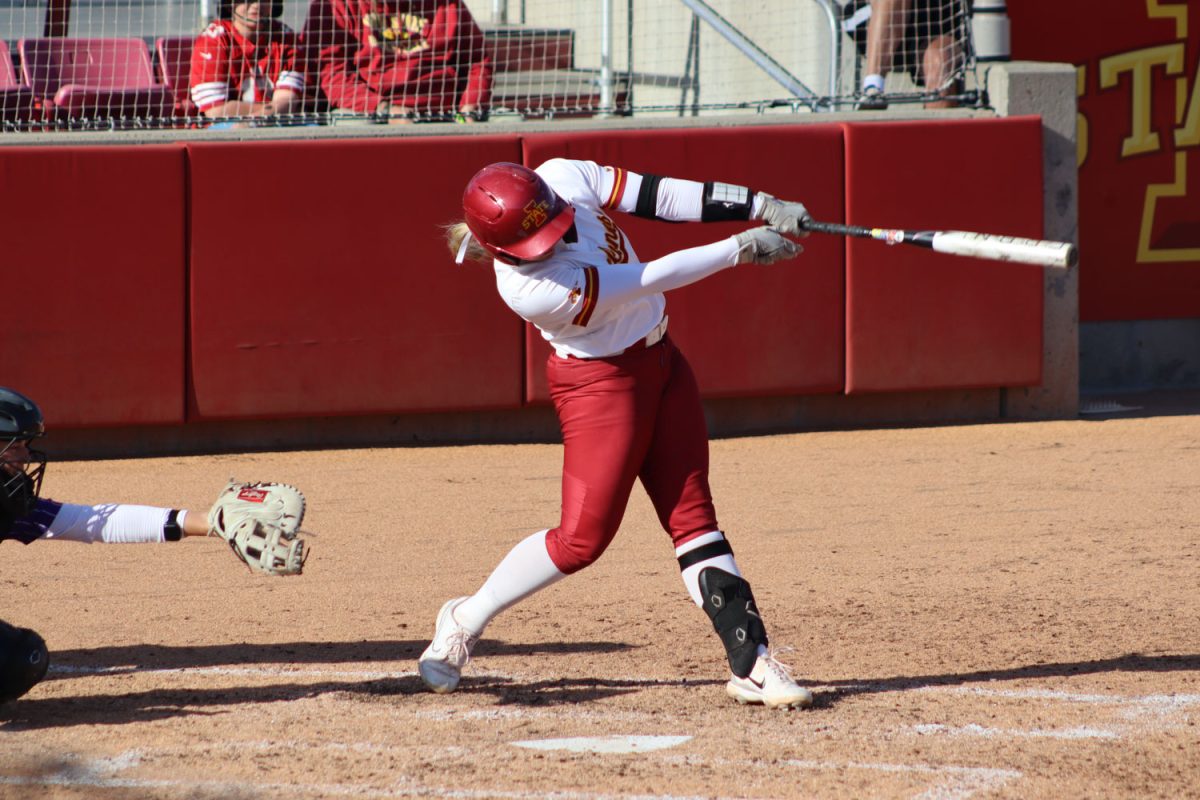

Gillian Holte/Iowa State Daily

Iowa State Instructor James Fay and the Industrial Engineering Department Chair Dr. Gül Kremer talk about the changing pad for babies Entrepreneurial Product Development Engineering Club invented. Fay graduated from Iowa State in chemical engineering in 1974 and is currently an instructor of Entrepreneurial Product Development Engineering.

April 29, 2019

Jim Fay walks meticulously around his classroom nestled in Howe Hall. He shifts his attention between the 14 students in the classroom, catching up after the nine-day spring break that Fay left just a little bit early for.

A red and orange classroom, the students sit scattered across the room in their blue, mobile chairs — none too far from the front. None too far from Fay.

He’s wearing a green and black argyle vest, with a light smile dressing his face.

On this particular day, Fay’s focus is on marketing. For students in his Entrepreneurial Product Development Engineering course, ENGR/IE 430, they can expect to stay on this topic for no more than a few class periods before moving on to character building.

It’s an accelerated course, but not because Fay is a fast talker or wants to cruise through the material. No, he’s a problem solver. And he needs to fit more than 40 years of experience in business within the parameters of a semester-long course.

But spend no longer than five minutes with Fay, and you’ll know he’s not one to shy away from a good challenge.

An Iowa State alum, Fay graduated in 1974 with a bachelor of science in chemical engineering. However, his education far extends his time spent in the classroom.

Equipped with the arsenal of a modern-day renaissance man, Fay’s wealth of knowledge extends from polymer chemistry and machine design to micro and macroeconomics, patent and contract law, strategy, statistics, market research, communication, marketing and more.

Yet his intelligence isn’t matched with intimidation. Rather, Fay has a peculiar way about him. He’s impassioned and humbled by his wit, the goal being to share in his experience instead of shielding it.

And that’s what brought him back to the higher education space, specifically Ames, Iowa, after 44 years away. This time standing at the front of the classroom — his attention solely focused on the students sitting before him.

But for Fay, his return to Iowa State is “easy and obvious.”

From a logistical standpoint, Fay sees the United States as one of the best in the world at inventing items and getting them to market.

But, there’s no class that teaches you how to do it, or at least no lesson plan sequestered within the four walls of a classroom that can quite match the education gained from the mistakes and successes built over a series of decades.

But that’s where Fay sees himself best fitting in — fostering the next generation of engineers that double as entrepreneurs, without having them experience the same level of hardships.

And, why Iowa State?

“Why not Iowa State? We have an incredible engineering college here,” Fay said. “I have my roots here. My objective is to make Iowa State the best in the world.”

Ask any of his students and they’ll tell you Fay is no ordinary professor. While many picked up his class on a whim the first time around, the impact Fay has been able to have on his students continues to amass.

Brian Fleming, senior in industrial engineering, learned quickly the influence Fay could have on his education. For Fleming, it was apparent on the first day of classes when Fay showed up in a full suit and tie — a lesson to always dress better than everyone else, especially when beginning a new job.

Fay is not a traditional professor, Fleming said, as he often does things in a way that feels random. Assignments change, but that’s OK. Fay didn’t just write the syllabus for the course, but the textbook too.

“He allows our creative brains to take over,” Fleming said, which has allowed him to think differently about how he views his other classes.

Coming from what Fleming describes as a very social and communicative industrial engineering department, he’s adjusted to frequent student-to-professor interactions.

So it only made sense that when Fleming and a fellow student wanted to know more about personal finance, Fay invited them over to his house. That particular day turned into a five-hour session.

Now, students can expect to be invited to Fay’s house on any given weekend dependent on the needs of the classroom, such as bread baking and butter making.

“He has time and he’s willing to share it with students,” Fleming said.

Nicholas Muehlbauer, senior in mechanical engineering, feels similarly.

In Fay’s 434 class, a secondary course aimed at implementing the skills learned in 430, Muehlbauer said he first heard of Fay’s class through a flyer advertising the course and its focus on product development — a topic Muehlbauer has taken special interest in.

Despite not taking the prerequisite 430 course, Muehlbauer was able to bypass the process because he joined the entrepreneur engineering club created in tandem with the class, which Fay advises.

Fay goes out of his way to make sure he’s available in any context or setting, Muehlbauer said. Whether through class or a club meeting, “you can tell how passionate he is about the material … our learning experience is very important to him.”

Riley Johanson, senior in industrial engineering, remembers his first day in Fay’s class and experienced Fay’s “tips.”

While oftentimes pieces of advice or applicable skills, the explanation of a “tip” could take as little as five minutes to an upward of half the class.

In his Tuesday class following spring break, Fay centered his tip on achievement: “Given the same objectives, boundary conditions, assumptions, facts and skills, bright people will reach the same conclusions.”

But on Johanson’s first day, Fay took a different approach: How to carry an individual twice your size out of a burning building using only a belt.

Someone volunteered to play unconscious while another individual offered up their belt, which later broke due to the activity.

“Jim is a person that you can learn a lot from,” Johanson said.

A mentor to many, Johanson recognizes the selflessness behind a man like Fay, who has found success time and time again, yet chooses to spend his time here — landlocked in Iowa surrounded by fields of corn and a lot of snow.

“He dedicates his time to being here,” Johanson said, describing Fay as altruistic. “I think that takes a very different person than who I am now.”

However, Fay’s attitude toward education hasn’t exactly aligned with the expectations of every student taking his class.

While some respect Fay instantly, whether due to his previous work experience or introspective personality, Fay’s teaching style didn’t quite click at first for Jacob Smidt, now graduated.

Smidt felt Fay treated his class more like a business than a learning opportunity — weeding out the students not dedicated enough to the work, like an employer might do in the hiring process or thereafter.

An example? A perfect class for Fay would be one not tethered to grades but rather takeaways and experiences.

Smidt felt this approach scared students, but he needed the class to graduate. He said he knew in the back of his mind that at minimum, he had to pass the course.

But Fay did what Fay does. He adapted.

“Over the course of 16 weeks,” Smidt said, “he changed the way he approached assignments, the way he approached grading and made a complete 180.”

While students are given projects to work on throughout the semester, the deadlines aren’t staggered. Rather, it is the student’s responsibility to manage their time effectively — similar to a professional project — to ensure the success of their grade.

Smidt also started taking advantage of the extracurricular opportunities offered by Fay, including “Sit and Sip,” in which students were invited to come out to Mother’s Pub with Fay and ask him anything.

One night, Smidt remembers, the group spent four hours talking about personal finance.

“If I would not have taken this class, I might not have invested in stocks and a 401k,” Smidt said.

And now that Smidt has joined the “real world,” he finds the confines of a “nine to five” no longer good enough.

The idea of making his own challenge has been intoxicating, Smidt said. But he never would have thought it was a possible “without that class to push me.”

So what’s motivated Fay to take on a course as alternative as this? For starters, his credentials are extensive.

Most notably, he founded the company that invented the Diaper Genie, which became the No. 1 non-disposable baby product in the United States. His work can also be attributed with Puffs facial tissue, Charmin toilet tissue and Bounty paper towels in addition to Huggies disposable diapers, Depends disposable undergarments, Pull-Ups disposable training pants and Starfire charcoal.

He founded ByteSize Systems, which enabled reading and annotating of majorly read books; and DEUS, which makes rescue equipment for professionals. As of most recently, Fay founded Spidescape, which makes shelter-in-place and self-rescue equipment.

Fay is also an avid outdoorsman, interested in biking, hiking and marathons. Over spring break, he even took a student on vacation to Colorado, the state he calls home, to stay in a hut on a mountain for a week with limited supplies and a heavy reliance on one’s ability to adapt to their surroundings.

“He’s very energetic in all that he does, he really genuinely cares that we get this information … he’s very personable,” said Kaitlyn Roling, teaching assistant for Fay’s 430 class.

While Roling took his course last semester and had a front row to see its evolution, Fay’s course objectives remain the same — teach the skills engineers need: competitive analysis, market research, concept development, product development, marketing, packaging, project management, prototyping, manufacturing, sales, customer service, finance, law and so much more.

Yes, all in just 16 weeks.

Roling sees the class as adding necessary skills to an engineer’s “toolbox.”

But it’s the little things, too, that make a big difference for Roling — like when Fay taught the entire class how to give a proper handshake. And what many students really enjoy about Fay is that he’s teaching them how to break out of the engineering mold.

Cameron Lynch, junior in industrial engineering, happened upon Fay’s class by accident. Due to taking time away from Iowa State for a co-op, Lynch randomly added Fay’s course as a tech elective.

However, he soon learned about the duality of engineering and life experience that Fay had to offer.

Lynch remembers when Fay challenged the class to come up with a way to obtain $10 million by the age of 65. While it doesn’t correlate directly to entrepreneurship, it better opened Lynch to the different ways that he could, and should, structure his life to meet the outcomes he’d prefer.

“This is a class that can change your mindset and how you see product development and the world,” Lynch said.

When Fay lectures, his students are in the moment — only a few times did a student take a quick glimpse at their phones, or perhaps draw their focus from Fay to jot down notes.

Fay often uses analogies when he speaks, which allows him to better explain a process or procedure in layman’s terms. In teaching his class how to “speak marketing,” he worked through the framework of different types of goods: search goods, experience goods and credence goods.

What differentiates them? Price. How do you define that price? Customer experience.

To explain this, Fay used the analogy of driving a car: “Sit in the seat and tell me how it feels.” It’s about loyalty, both behavioral and brand based.

Yet, as he lectures, time creeps up on Fay. The class is just an hour and a half but he has decades of knowledge he still has to relay.

“I’ve got one minute,” Fay says before speeding through his last slides.

The class runs three minutes past 2:10 p.m.

“I’m over, I apologize,” Fay said. He requests that students think of good questions to ask for an upcoming lecture. “Be alive.”