Catt Hall: Why we can’t “get over it”

March 25, 1997

The history of the United States is often described in terms of great men (and occasionally women) making great sacrifices and taking great actions to improve our condition and move us ever forward. Catt has been sold to us as one of these “great men,” in spite of her gender; often her defenders point out that we have honored many men who were undoubtedly at least as racist and elitist as Catt, if not more so. Without Catt, women might not have attained suffrage until the second World War, they claim, clinging to the belief that change is the product of action on the part of exemplary individuals.

I do not wish to argue with the importance of individual commitment; I would, however, point out that Catt did not single-handedly secure the vote for women. She was part of a mass movement — a leader, to be sure, and a woman of many accomplishments — but she did not act alone. Her political ideology was, in fact, quite mainstream (the historian Linda Schott refers to her as “middle-of-the-road” in her work “‘Middle-of-the-Road Activists: Carrie Chapman Catt and the National Committee on the Cause and Cure of War” [Peace and Change 21:1 (January 1996) 1-21]).

Therein lies the problem: the mainstream political ideology of the time was exclusionary, devoted (as power always is) to retaining power in the hands of the few who thought themselves qualified to wield it. In one sense, Catt’s defenders are absolutely right: she did nothing that was uncommon in her time. Her attitudes toward racial minorities, immigrants, and the working class were in keeping with her own social construction: a privileged, well-educated white woman.

The problem manifests itself when, as in the case of the university, “Catt in context” comes to mean only the context of her own white privilege. If she is to be held to the standards of the power elite, of course there is nothing problematic about her rhetoric; it reinforces everything the privileged hold dear.

But if, as the administration constantly tells us, we are committed to diversity here at I.S.U., then we must find a way to open the narrative of history — what some historians call the master narrative — so that the voices of others are heard. Those other voices, which are also Other because they represent the experience of excluded people, at the very least disrupt the efforts at canonizing Catt among our pantheon of cultural heroes.

White privilege allows us to read her words and say, “Well, she only said that for political expediency.” Or, “she didn’t mean it the way it sounded.”

Through eyes not blinded by white privilege, we can see political expediency for the ruse it is, since it always profits politically at the expense of the Other, and is, in fact, far more morally offensive because it means that a public figure knew better and chose the low road anyway. As Osha Gray Davidson, noted author, remarked in his recent (February 4, 1997) speech at I.S.U., “There is a special circle of hell reserved for politically expedient racists.”

As morally repugnant as racism is — and if we can’t agree on that, we are in a world of hurt — political racism is even more so. It indicates a human so devoted to success at any price that she would be willing to knowingly do what she believed to be wrong in order to achieve her goals.

This “end justifies the means” argument is analogous to an argument which says Mussolini’s fascism may have been unpleasant, but it was what was necessary to bring order to Italy and keep the trains running on time. A culture which embraces (or claims to embrace) the moral high ground when mouthing support for diversity and multiculturalism loses all credibility when it then turns to arguments in which expediency justifies oppression.

The second argument, that Catt wrote something other than what she really meant, is equally useless. Either she did so unintentionally, in which case she is hardly the exemplary rhetorician we have been offered as a heroine, or she deliberately covered over her meaning in such a way that racists would be happy with her arguments.

A desire to “tickle the ears” of one’s audience may lead to a successful political campaign, but it hardly qualifies such a person for the sort of accolades and adoration our administration would have us shower on Catt. Such an argument — intentional duplicity in the interest of a so-called political advantage — leads us to the same question of morality addressed above, and, ultimately, to the same answer: it just won’t wash.

That we are holding Catt to a higher standard of conduct than many men for whom I.S.U. has named buildings is in fact the case, but only because we weren’t around when those buildings were named. To name a building after a person is to endorse what they stood for; it is to accept the person and his or her life as a symbol of what we believe in now.

If a building had been named for Catt in the mid-seventies, when it was first suggested, it would have undoubtedly passed without comment. The reason is not a pretty one: the voices of the Other were still so far on the margins as to be unheard in the discourse of this institution. But rest assured, our offense at Catt is not related to her gender. If the administration suggested that we name a building for Andrew Jackson next week, many of us would be waving copies of the Indian Removal Act in a heartbeat. Someone suggests naming a building for Franklin D. Roosevelt?

Here, let me show you Executive Order 9066. We would, and will, say exactly the same things about any attempt to install a symbol that is offensive to marginalized people, that shows a lack of respect for multiculturalism and contradicts the university’s so-called commitment to diversity.

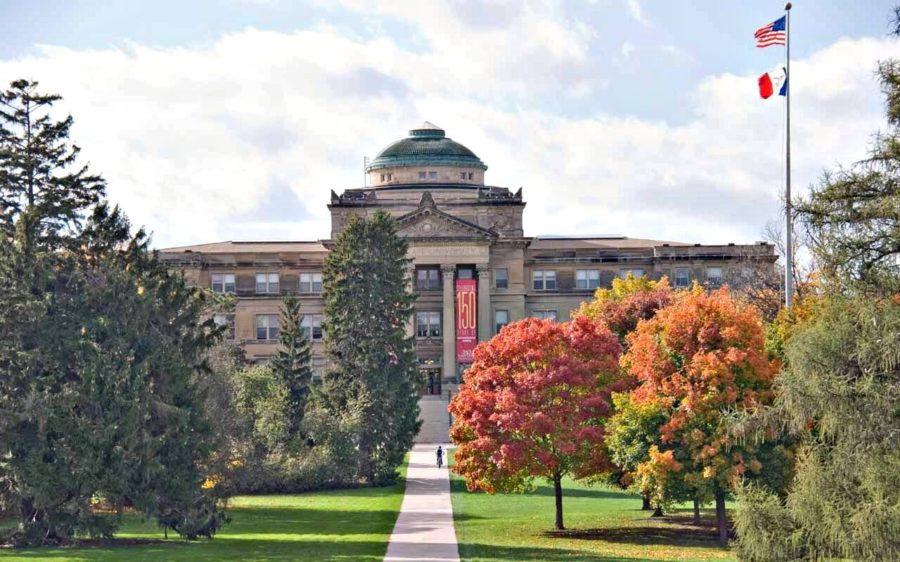

We have said repeatedly that Catt Hall is a symbol. By that we mean that it is an object that stands in the place of or represents something other than itself. Catt Hall stands for the university, and if, as one of the members of The September 29th Movement is fond of saying, the administration won’t even discuss a symbol in a mediated environment where the institution cannot flex its considerable muscles, then how in the name of all that is holy can we expect the university to engage in dialogue with us on issues that are other than symbolic?

A symbolic victory can often be the best kind of victory, for it indicates a willingness to exchange one way of thinking, one way of seeing the world, for another. We want a symbolic victory: a new way of perceiving power and diversity on this campus.

Where Catt Hall is concerned, we can’t “get over it.”

Kel Munger is a graduate student in English and a member of The September 29th Movement’s central committee. This is the second part of a two-part letter.