Ziemann: The great grad school debate

July 22, 2020

Editor’s Note: This is the first of two columns concerning graduate school conducted by Megan Ziemann.

I chose the absolute worst time to second-guess my major. It was Winter Break before my second semester of junior year, I had just received feedback from professors on my final projects from the previous semester and one of those bits of feedback kept sticking.

It was a message from my gender and consumer culture professor. He told me I would be a great candidate for a sociology or gender studies graduate program.

I had been toying with the idea of a Master of Business Administration (MBA) for the past couple of years, but it was that gender and consumer culture class that made me realize I was not cut out for an MBA.

In fact, it was that gender and consumer culture class that made me realize I should have double majored in marketing and sociology.

Or just majored in sociology.

That message was the straw that broke the camel’s back. I was sick of the pro-capitalist textbooks. I was sick of the speakers that would come into my classes and objectify their customers. I was sick of the “buy, buy, buy” culture I was being taught to value.

But I was going into my last few semesters at Iowa State. I had sunk too much into this marketing degree, and I couldn’t stop now. It would have been a huge waste of time and money.

And deep down, I like what I do. I like managing social media. I like connecting people with products, services or ideas that will make their lives better.

So, I spent that Winter Break researching. Maybe there was some sort of program that could marry my two passions — something that could harness my marketing skills but had a social justice focus.

As I was pouring over sales pitches from schools I could never afford, I realized my need for a grad program was stemming from something deeper.

You see, I was a “gifted kid.” I’ve always been told I have potential, I was a joy to have in class, I required more work in order to be challenged. In elementary and middle school, I made being in the gifted and talented program a part of my personality (cringe). In high school, I took every Advanced Placement (AP) and dual-enrollment class I could.

This is gifted kid syndrome. Adults formerly labeled as “gifted” have been told they must amount to something. They’re told they have something special, and if they don’t use that gift to go above and beyond in every aspect of their lives, they’re depriving the world of that gift.

Gifted kid syndrome obviously presents itself in children as well as adults. Gifted children are prone to emotional issues like hypersensitivity and perfectionism, and if left untreated or enhanced by a gifted and talented program in the child’s school, that hypersensitivity and perfectionism manifests in the child’s adult life as well.

Let’s talk about these gifted programs for a minute. Honestly, I loved mine in elementary and middle school. I loved meeting kids who solved problems the same way I did. We worked together well, completed cool projects (hello Math Olympiads, Reading Relays and Destination Imagination instant challenges) and had a really nice community during a time when kids really needed friends.

But I’m white. And almost all of the other kids in my program were white. And my school district wasn’t the only one with this problem.

It’s systemic. A lot of gifted programs require some sort of entrance exam coupled with parental permission. These exams can be biased toward white children, and due to job discrimination the parents of Black, Indigenous and people of color children may not be able to be as involved as parents of white children. The programs themselves are expensive for schools to access, so the more affluent (read: the whiter) a school district, the better gifted program they will have.

Formerly gifted kids may also experience symptoms of mental illnesses like depression, anxiety and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). If you’ve read some of my previous work with the Daily, you’ll know that applies to me.

And if you know me outside of the Daily, you’ll know that I suffer from pretty severe perfectionism.

I believe I do not have the privilege of messing up. I have to do everything right the first time, and if that isn’t the case, I am a failure and do not deserve the positions I hold.

In my mind, I do not have the option to mess up college. I was gifted then, so I must be gifted now. And what do ex-gifted kids do?

They go to grad school.

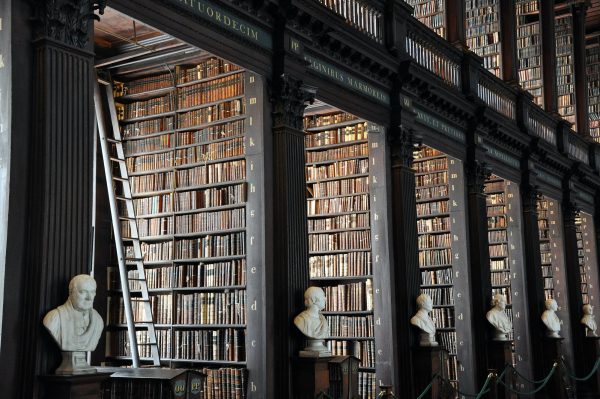

My grad school dreams also come from a deeper insecurity. I get school. I’m good at school. I understand it, and I can excel in it.

But I don’t know what industry is like. All of my jobs in college have been affiliated with the university in some way, and I did that on purpose. My comfort zone feels good. School feels good. Why leave it?

Formerly gifted kids are stuck in a box. We’ve been told we’re good at one thing our whole lives, and when that thing ends, it’s scary. It’s time we separate school from our giftedness, because being gifted doesn’t have to mean being booksmart. You can be gifted in extroversion, gifted in music and art, gifted in so many other things that are not reading from a textbook and regurgitating information.

For those of us who are still thinking about grad school, I’m with you. It’s not my fault I genuinely enjoy reading academic jargon. I’m still keeping that grad program in mind — in fact, I will have a master’s by the time I reach 30.

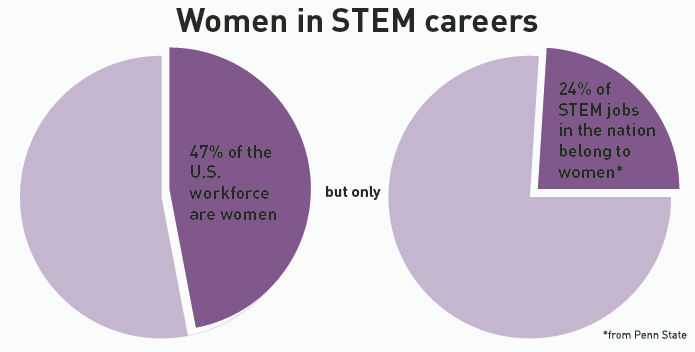

But we have to apply the same scrutiny we have for gifted programs to graduate schools and their application processes. Never forget racism, classism and sexism are systemic.

Having a couple of letters before or after your name does not make you the next Einstein.

Your degree doesn’t define you.

What you do with it does.