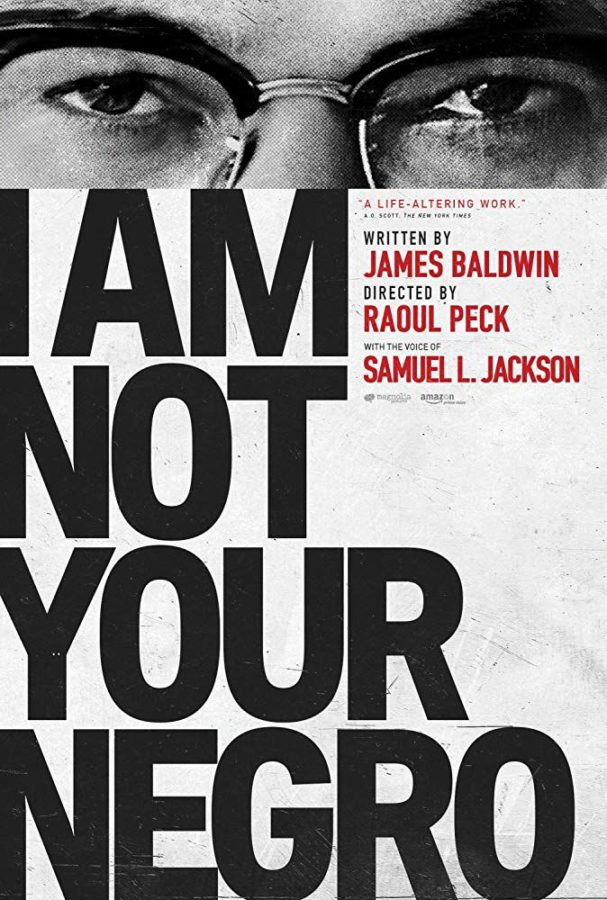

Parks Library screens the film “I am Not Your Negro” in honor of Black History Month

The 2016 film “I Am Not Your Negro” is based upon the unfinished novel “Remember This House” by author James Baldwin. The film is about the lives and assassinations of Medgar Evers, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. and explores the continued peril America faces from institutionalized racism.

February 13, 2020

As a part of Black History Month, Parks Library presented the film “I Am Not Your Negro” on Thursday to a room of 13 people.

The film highlights the assassinations of Medgar Evers, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr., three close and very different friends of the author James Baldwin. It brings to life a radical perspective on the recent racial narrative and relations in America based on Baldwin’s incomplete novel “Remember This House”.

“The question is really a kind of apathy and ignorance, which is the price we pay for segregation,” James Baldwin said. “That’s what segregation means. You don’t know what’s happening on the other side of the wall, because you don’t want to know.”

The film used Baldwin’s own words and writings from a short manuscript about his exterior role as a self-described witness in the civil rights movement and was narrated by celebrity Samuel L. Jackson.

The film addresses hate crime, human rights, slavery in the U.S. and lynching. “I Am Not Your Negro” is a journey into black history that connects the past of the civil rights movement to the present of #BlackLivesMatter.

The civil rights movement began in the late 1940s and ended in the late 1960s. The movement was mostly nonviolent and resulted in laws to protect every American’s constitutional rights, regardless of color, race, sex or national origin.

“I remember, for example, when the ex-Attorney General, Mr. Robert Kennedy, said that it was conceivable that in forty years in America we might have a Negro president,” Baldwin said. “And that sounded like a very emancipated statement, I suppose, to white people. They were not in Harlem when this statement was first heard. They did not hear the laughter and the bitterness and the scorn with which this statement was greeted. From the point of view of the man in the Harlem barbershop, Bobby Kennedy only got here yesterday and now he’s already on his way to the presidency. We’ve been here for four hundred years and now he tells us that maybe in forty years, if you’re good, we may let you become president.”

To put that in perspective it was in 1968 when Robert Kennedy made this statement and it was not until 2008 that President Barack Obama made history as the first black elected president 40 years later.

Some of the most historically memorable moments and people surrounding the movement included and featured in the film are: 15-year-old Dorothy Counts, the first black integrated student of Charlotte, North Carolina; Black Panthers; Lorraine Hansberry; Martin Luther King Jr. and the March on Washington; the assassination of Malcolm X; the sit-in involving four African American college students in North Carolina; the “Little Rock Nine” blocked from integrating into Little Rock Central High School in Arkansas; the Freedom Rides; “Bloody Sunday” and the Selma to Montgomery march.

The film first follows the stories of affluent leaders of the civil rights movement including Malcom X, also known as El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz, an American Muslim minister and human rights activist. It tells the story of the activities leading up to his famous assassination on February 21, 1965, as a man rushed up and shot him once in the chest with a sawed-off shotgun and two other men charged the stage firing semi-automatic handguns in total, numbering 21 gunshots.

Following news of Malcolm X’s death, author James Baldwin was torn up and famously declared to reporters interviewing him, “You did it! It is because of you—the men that created this white supremacy—that this man is dead. You are not guilty, but you did it […] Your mills, your cities, your rape of a continent started all this,” according to the novel “On the Side of My People: A Religious Life of Malcolm X,” by Louis A. DeCaro.

The film also briefly tells the story of Medgar Evers; an American civil rights activist in Mississippi, the state’s field secretary for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and a World War II veteran who had served in the United States Army. It also portrays Evers’ assassination as he was struck in the back with a bullet and died shortly after being admitted as the first black patient at an all white hospital facility. A funeral procession of nearly 5,000 led by civil rights leaders Allen Johnson, Reverend Martin Luther King and others followed suit.

The film additionally highlights the life of Martin Luther King Jr., an American Christian minister and activist who became the most visible spokesperson and leader in the civil rights movement leading up to his death when he was fatally shot by James Earl Ray at 6:01 p.m., April 4, 1968, from the Lorraine motel’s second-floor balcony in Memphis. The assassination led to a nationwide wave of race riots in Washington, D.C., Chicago, Baltimore, Louisville, Kansas City and dozens of other cities and the establishment of an annual holiday to honor King known as Martin Luther King Jr. Day.

“The root of the black man’s hatred is rage, and he does not so much hate the white man as simply as want the out of his way, and, more than that, out of his children’s way,” Baldwin said. “The root of the white man’s hatred is terror, a bottomless and nameless terror, which focuses on this dread figure, an entity which lives only in his mind.”

The movie featured classic musical works recognizing black artists of several eras in the soundtrack including: “The Ballad of Birmingham,” “Damn Right I’ve Got The Blues,” “The Jailhouse Blues,” “Just A Dream (On My Mind),” “Big Road Blues,” “Baby,” “Please Don’t Go,” “Route 66,” “Black Brown and White,” “Stormy Weather,” “People Get Up And Drive Your Funky Soul,” “Take My Hand Precious Lord” and “The Blacker The Berry.”

It also paid tribute to more recent victims of police brutality including Tamir Rice, Darius Simmons, Trayvon Martin, Aiyana Stanley-Jones, Christopher McCray, Cameron Tillman and Amir Brooks.

It examined typical Hollywood stereotypes of the black menace and subservience through the visual representation in clips of scenes from other films and movies including “Dance, Fools, Dance’” “Imitation of Life,” “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner,” “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” and more.

“History is not the past,” Baldwin said. “It is the present. We carry our history with us. We are our history. If we pretend otherwise, we are literally criminals. I attest to this: the world is not white; it never was white, cannot be white. White is a metaphor for power, and that is simply a way of describing Chase Manhattan Bank.”

The film is available for Iowa State students or those with a Kanopy streaming account for free viewing, through Amazon Prime video for 99 cents, YouTube, Vudu or Google Play Movies & TV for $2.99, iTunes for $4.99 and additional streaming services. A limited number of physical copies are also available for checkout at Parks Library.