Your donation will support the student journalists of the Iowa State Daily. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment, send our student journalists to conferences and off-set their cost of living so they can continue to do best-in-the-nation work at the Iowa State Daily.

‘Yore was gonna be a leader’: The life of Yore Jieng

May 25, 2023

This series examines the life, death and impact of Yore Jieng. The reporting for this article was original and conducted by a team of reporters from Iowa State University from March until May. Submit tips regarding Yore Jieng at Crime Stoppers of Central Iowa.

Iowa State’s Hilton Coliseum buzzes from the sounds and sights of excited basketball fans. Kids beg their parents for a cardinal and gold ice cream cone while the families of the players anxiously wait for the game to start. The student section grows more and more packed the closer it gets to tip-off.

The announcer starts to list off the opposing team’s players. Soon, the lights dim, and the familiar sound of the Cyclone Weather Alert siren begins to fill Hilton as Jock Jams MegaMix blares. With booms from the loudspeaker and deafening cheers from the fans, the Cyclones’ first player steps onto the floor.

“A junior from Des Moines, Iowa, Yore Jieng,” the announcer yells as Hilton erupts with applause. Yore runs onto the court and takes a look around, soaking in the Hilton Magic. Cyclone fans from near and far cheer him on, excitedly waiting for him to lead the team to another home victory.

But this never happened.

Yore never played basketball for Iowa State. In fact, he never attended Iowa State or even graduated from high school.

Yore was killed by a gunshot to the head in 2016 when he was 14 years old. No one has been arrested for his death.

This series examines the life, death and impact of Yore Jieng. The reporting for this article was original and was conducted by a team of reporters from Iowa State University from March until May.

‘Yore didn’t fold’

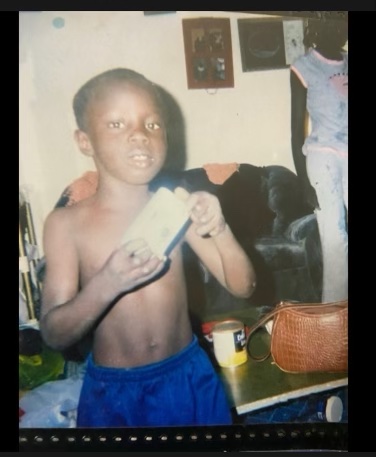

According to Nyekuoth Jieng, Yore’s older sister, he was always playing basketball.

“I loved watching him play basketball because he was just so good at it,” Nyekuoth said. “It was almost like it came easily to him.”

Nyekuoth said Yore, who would have turned 21 on May 26, had webbed skin between his fingers that made his hand look like it was making a “rockstar” symbol, but that never stopped him from playing with the rest of his friends and teammates.

Peter Ngo, a friend of Yore’s, remembered him as outgoing and confident. He said Yore would not tolerate disrespect from anyone.

“When we get on the court, you know, [there are] dudes trying to bully and push, and Yore didn’t fold,” Ngo said.

Ngo looked up to Yore for his courage and confidence, even though Yore was younger.

The time Ngo and Yore spent together was more than just playing basketball. Ngo said Yore and their friends would often stay outside until midnight or 2 a.m., talking and looking at the stars.

“We just sit there. You see the stars, the moon,” Ngo said. “You know, Yore would crack a couple of jokes then and there, and we would just burst out laughing. It was just a great time.”

Nyeduel Jieng, Yore’s older sister, said Yore was always joking around. She described him as “the annoying little brother everybody has.”

John Lamb, Yore’s basketball coach and mentor, remembered his time coaching Yore and his friends.

“They’re lovable kids,” Lamb said. “It was all long and gangly and just happy, and that’s how I remember Yore. We just had a crew, man.”

Lamb said Yore stood out from others.

“You could tell Yore was gonna be a leader,” Lamb said.

Lamb met Yore through helping Sudanese mothers by watching their kids while they were working. He would pick up kids from Des Moines to go work out and play basketball, sometimes driving over 100 miles in a day.

Lamb said Yore had a fearless spirit, and he would often approach Lamb’s car before anyone else.

“He would run up to the car, 10 o’clock at night,” Lamb said.

No one ran up to Lamb’s car like Yore did. Despite all of Yore’s friends knowing whose car it was, Yore was the most enthusiastic.

Ngo said Yore’s uplifting and positive spirit was the connection of the group. Yore would not let negativity drive a wedge between him and his teammates.

“For example, we hate this group of guys, or we hate this,” Ngo said. “But I say one thing Yore does; I say he brings us together, no matter who you hate.”

Caught between two worlds

The Rev. Minna Bothwell of Capitol Hill Lutheran Church, which Yore and his family attended, agreed that Yore was different from other kids his age. Bothwell said Yore, who also regularly attended Zion Lutheran Church’s youth programs, always remained true to himself and did not care about others’ opinions of him.

Both Bothwell and Lamb said Yore always had a smile on his face and was a happy person who was willing to step up when no one else would. One of Bothwell’s favorite memories of Yore was when the role of King Herod in the Christmas program opened up on Christmas morning, and Yore stepped up without hesitation.

Bothwell said Yore’s family still regularly attends church.

Yore was a first-generation American, as his parents were born in Sudan. They immigrated to the United States and landed in Des Moines, Iowa, where Yore was born and raised. At the time of Yore’s passing, he and his family lived in Oakridge Neighborhood, a housing complex in Des Moines.

According to Bothwell, it can be difficult to grow up with parents who were not born in the United States. She said the children are often caught between the South Sudanese and American cultures.

“They’re caught between these two worlds,” Bothwell said. “There’s a whole lot of baggage that they carry in regards to where they belong [and] their identity.”

Bringing everyone together

Bothwell said this cultural difference can be a source of friction and violence. However, for Yore and his friends, the cultural differences brought them closer together.

Ngo said the differences between South Sudanese and American cultures were a commonality between himself and Yore. Ngo said the children of South Sudanese immigrants bond over the fact.

“Whenever people get together, the Sudanese community, they really get things done,” Ngo said.

According to Ngo, when an event happens in the Sudanese community, whether it is positive or negative, everyone comes together as part of Sudanese tradition.

Bothwell said this was the case after Yore’s death. Even people who didn’t know Yore personally showed support for him and his family.

A funeral and vigil were held after Yore passed away, drawing a crowd of over 600 people. Bothwell, who spoke at Yore’s graveside service, said it was one of the largest crowds she has seen in her career.

Ngo said that Yore’s death “really hurt the community.”

The community continues to grieve Yore’s death and what his life could have been.

Yore was only a freshman at Roosevelt High School when he was killed.

“He was 14 at the time, so he had a long ways to know who he was going to be [and] where he was going to end up,” Nyeduel said. “He didn’t get to where he wanted to be in life because his life was cut short.”

Read part two regarding the investigation of Yore’s death.