Dan David Prize recipient to lecture in R.A.T.E. program

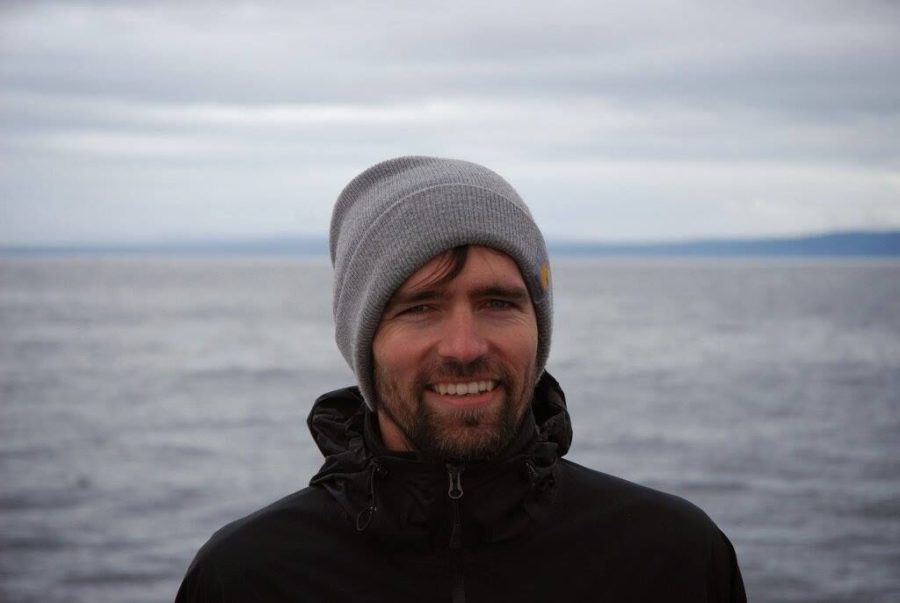

Image courtesy of Bartow Elmore

Bartow Elmore is an Associate Professor at Ohio State University and author of the books “Seed Money: Monsanto’s Past and Our Food Future” and “Citizen Coke: The Making of Coca-Cola Capitalism” and a 2022 recipient of the David Dan Prize.

March 2, 2022

A recent recipient of the Dan David Prize, Bartow Elmore, will lecture on his most recent book to students of the Rural Agricultural Technological Environmental Ph.D. program (R.A.T.E.)

In addition to looking into the behaviors of various large corporations, Elmore is an associate professor at Ohio State University. He will be speaking at Iowa State as a part of the R.A.T.E. Ph.D. program in the history dept. The lecture will take place at 6:00 p.m. in room 2432 of the Food Science Building.

The Dan David Prize was first started in 2001 by Dan David. Since Dan David’s death in 2011, Ariel David, Dan’s son, has taken over the foundation and reimagined the prize. The updated prize focuses on mid-career researchers with a focus on history, awarding nine recipients a year with a $300,000 grant.

Elmore won the Dan David prize for his research and recent book, “Seed Money: Monsanto’s Past and Our Food Future.” In the book, Elmore explored the rise of Monsanto during the 20th century and the nearly universal usage of their various herbicidal chemicals.

“I think one of the biggest takeaways was that kind of the future of food was so tethered to a chemical past,” Elmore said. “And in so many ways, we’re being promised this kind of innovative new future with these genetically engineered seeds that when I looked at, it looked again, like old chemistry in so many ways.”

Elmore described the current predicament that the agricultural field finds itself in as weeds develop resistance to chemicals like Roundup. To cope with these changes, Monsanto opts to sell older versions of similar products like Dicamba and 2,4-d and accompanying herbicide-resistant seeds.

“You’re seeing this kind of system, this kinda almost blunt force model of dealing with weeds, that no matter what it is, you have created a new kind of weed killer like this,” Elmore said. “It’s gonna have this fatal flaw that is, it’s going to promote this selective pressure that’s going to result and adaptation that will ultimately need a new fix.”

Elmore continued to say that while this business model is not beneficial for farmers, consumers and the world, it is very profitable for Monsanto. Such a chemical-heavy model relies on the creation of new and effective herbicides, which as Elmore points out, hasn’t really happened since the 70s.

Elmore’s research looking into the patterns of behavior within large corporations like Monsanto, CocaCola and FedEx helps to expose trends of dishonest and misleading behavior. One example of such behavior mentioned by Elmore is the efficiency distraction, in which companies phrase their greenhouse gas emissions in terms of efficiency, comparing their emissions to the revenue they generate.

Despite companies boasting decreases in their “emission intensity”, their total emissions often end up increasing as the company grows.

“Looking at history, when talking about questions of corporate sustainability most people would say ‘I don’t get any of that,’ right,” Elmore said. “It’s always about kind of new metrics or new technologies or new ideas. And that’s one of the things I think our history department at Ohio State is trying to model for the country is the importance of including history in discussions of corporate sustainability in business schools and business curricula for students.”