- App Content

- App Content / News

- News

- News / Politics And Administration

- News / Politics And Administration / City

Net neutrality repealed: what that could mean for Ames

Graphic: Logan Gaedke/Iowa State Daily

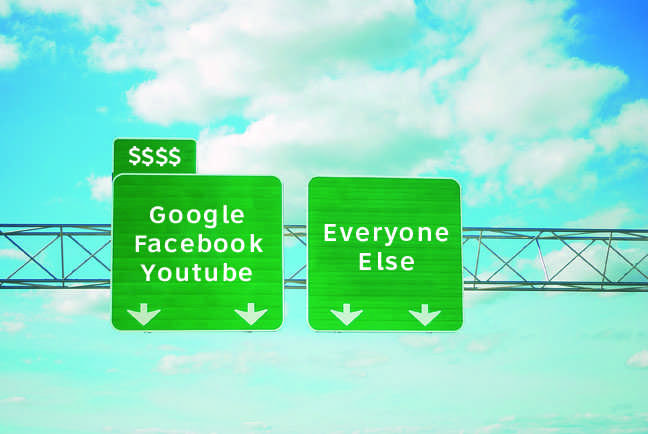

Columnist Rick Hanton believes we should give the FCC the power to maintain net neutrality, so as not to push out smaller, less profitable website sources from the public’s view.

June 21, 2018

With net neutrality gone, most internet companies won’t change their policies in the short term, but over time, they could start charging more for less, says a former computer science professor with 35 years of experience.

“It has only been one week without net neutrality, so we haven’t felt the impacts yet, but that could change over the next few years,” said David Martin, who is now a computer software consultant and Ames City Council member. “Right now, the internet is dominated by a few big names: You have Amazon, Netflix, Facebook, Twitter and they want to keep it that way.

“To them bigger is better, and what will the shareholders want? They will take steps to prevent competition and control the market. If I were a shareholder in one of those companies, I would be asking them why they aren’t taking those steps.”

Net neutrality was a policy, implemented during President Barack Obama’s time in office, restricting internet service providers from slowing down or speeding up access to different websites. It ended on June 11 after the Federal Communications Commission voted to get rid of it on a 2-1 vote.

“Every time someone browses the internet, that data first goes through an internet service provider or ISP,” Martin said. “These ISPs can handle that data and choose to limit or speed up access to different websites.”

The practice of speeding up or slowing access, also known as throttling, was prevented by net neutrality. As these companies are allowed to throttle, Martin said, they stifle competition on the internet and allow larger companies to stay on top in perpetuity.

“Large companies like Netflix could pay a little extra to limit access to other streaming services or make their services faster,” Martin said. “This would essentially choke out other companies.

“Right now the largest streaming service is Netflix, but years from now it could be some unknown company who hasn’t emerged yet,” he said. “With net neutrality gone, those companies might not emerge.”

FCC Chairman Ajit Pai, who oversaw the removal of net neutrality, says the policy will actually increase competition.

“[Net neutrality] will protect consumers and promote better, faster internet access and more competition,” Pai told CBS News on June 11. “But at the FCC, we have a transparency rule where every company in the U.S. has to disclose their business practices, and the Federal Trade Commission is empowered to take action against any company who engages in any anti-competitive conducts.”

Calling net neutrality a “solution in search of a problem,” Pai said ISP’s will not throttle despite the regulations being removed. When asked about Comcast’s practice of throttling BitTorrent, a peer-to-peer file sharing service, in 2010, Pai released a proposal in which he said it is unlikely to happen again.

“We do not believe hypothetical harms, unsupported by empirical data, economic theory, or even recent anecdotes, provide a basis for public utility regulation of ISPs,” Pai said in the proposal.

Pai has also argued the removal of net neutrality would improve competition by allowing ISPs to split up access to the internet like cable packages.

Instead of an all-inclusive internet plan, an ISP could restrict access to social media websites, streaming services, online games or email services unless customers buy those respective packages.

“Plans like that aren’t theoretical; they have actually happened,” Martin said. “Places around the world without net neutrality, like Portugal, have split plans into packages at the cost of the consumer.”

Martin said this problem could be worse in areas where customers don’t have alternatives.

“In Ames, if you want high-speed internet, then Mediacom is really your only option,” he said. “Mediacom will listen to its shareholders over its customers when their customers have no alternative. So ISPs will have a profit motive as well as pressure from shareholders to take advantage of these changes.”

Martin said the lack of competition and service has spurred his own interest in pursuing a city-driven internet provider in Ames.

“As a city utility, Ames would be able to make its own rules and regulations that guarantee the protection of local net neutrality,” Martin said. “We would be answerable to the voters of the city, rather than shareholders.”

Local actions aren’t the only solution some have thought of to reimplement net neutrality. A recent lawsuit could revert some changes for a short time.

“The FCC did a complete 180 when they decided to repeal net neutrality,” Martin said. “The lawsuit is on the basis that this quick change sort of undermined the typical rules-making processes of federal agencies.”

If this lawsuit were lost, Martin said, there would likely be an injunction as the FCC revisits its decision-making process to repeal the rules. In other words, net neutrality could come back as a federal regulation for a short period of time.

Editor’s note: This article has been updated due to an error. David Martin was not a former professor at Iowa State, but he was a professor for nine years at the University of Denver and University of Massachusetts Lowell. The Daily regrets this error