Ames reverend, immigrant bible scholar respond to U.S. Attorney General’s bible reference

June 24, 2018

Endeavors in the Trump Administration’s immigration policy saw thousands of children separated from their parents in a matter of weeks, and Attorney General Jeff Sessions offered some unexpected spiritual consolation to concerned Christians earlier this June.

In a move that some Ames religious leaders, scholars and immigrants found confusing, Sessions justified the immigration policy by quoting the New Testament.

Sessions cited Romans 13, saying people should “obey the laws of the government because God has ordained the government for his purposes,” before an audience of law enforcement officers in Fort Wayne, Indiana on June 14.

Sessions is a United Methodist, which means he shares a denomination with Reverend Jill Sanders of the Ames Collegiate United Methodist Church, but the differences in their scriptural interpretations is stark.

“I have two problems with his use of the scripture,” Sanders said. “First, he’s assuming the text is authoritative in the government. And second, he’s cherry picking. What about how we’re supposed to treat strangers and immigrants? I didn’t hear him mention that when he was quoting the Bible.”

Sanders also has a problem with the principle of Sessions relying on scripture to rationalize administrative policy.

“I have no problem with a leader being informed by their faith, but you need to be sensitive to other faiths,” Sanders said. “To apply scripture to a law in a secular country and expect everyone to view that as binding is confusing.”

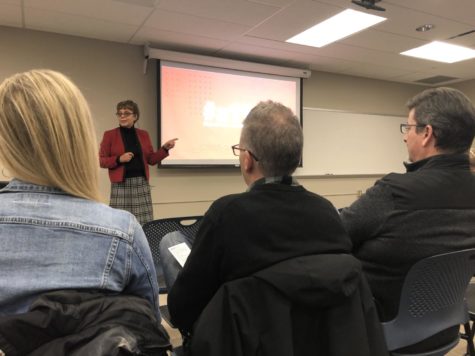

These issues Sanders brought up seem to be a popular observation in the Ames community. Hector Avalos, Biblical scholar and professor of religious studies at Iowa State, recently wrote an article which challenged the very idea of using sacred texts to dictate moral behavior.

“A biblical view on immigration is irrelevant,” writes Avalos. “Because it is immoral to use a sacred text to authorize any moral behavior or social policy.”

Avalos immigrated to the United States from Mexico when he was a child, and witnessed the deportation of family members growing up in Glendale, Arizona in the late 1960s. Since he was the only one in his family that knew any English, the young Avalos would serve as an interpreter between immigration officers and his detained family.

In particular, Avalos remembers speaking on behalf of his cousin after she was apprehended by Immigration and Naturalization Services (INS).

“It is one thing to be an immigrant from an English-speaking country or an immigrant with English-speaking abilities,” Avalos said. “It is another thing to confront official authority figures, especially as a female, when you understand little or nothing of what is being said to you.”

In his article, Avalos describes several other incidents where he was accosted by the INS, which is now called ICE (Immigration and Customs Enforcement). However, he mainly focuses on the title and thesis of the article, that “the Bible is not a friend of immigrants.”

“The Bible is too morally contradictory to be a friend to immigrants,” Avalos wrote. “For every immigrant-friendly prooftext, someone else can find one that says the opposite.”

For example, scripture such as James 1:27, which calls for Christians to “to care for orphans and widows in their distress,” or the parable of the Good Samaritan seem like valid evidence Christians ought to be accepting of immigrants.

Likewise, Jesus is often quoted from Matthew 25 saying, “Truly, I say to you, as you did it to one of the least of these my brethren, you did it to me…for I was hungry and you gave me no food, I was thirsty and you gave me no drink, I was a stranger and you did not welcome me, naked and you did not clothe me, sick and in prison and you did not visit me.”

However, there is conflicting opinion about whether or not Jesus means everybody when he says “brethren,” or if he is only referring to fellow Christians.

Avalos is also quick to point out passages in the Bible that aren’t so friendly towards foreigners, such as Numbers 31:16-17 which instructs believers to “kill every male among the little ones, and kill every woman who has known man by lying with him,” and to only spare the lives of virgin women and girls.

This passage is speaking particularly about a time when the Israelites were at war, but Avalos doesn’t find that to be a valid justification of the doctrine.

“This practice would be held as immoral today,” Avalos wrote. “Whether in war or in peace.”

Jesus may have lauded the Good Samaritan for aiding a stranger without inquiry, but he also hesitates in helping the sick child of a foreign woman in Matthew 21, and even refers to the estranged woman as a “dog.”

Sanders view of the Bible and immigration differs from Avalos. She interprets the will of Jesus Christ as one that is more friendly to immigrants than anything else.

“My faith teaches that we’re supposed to go to the margins and help the orphans, the widows, the stranger at the gates,” Sanders said. “I believe if Jesus were among us today, he’d be at these camps in Texas right now, and not at church meetings.”

Sanders isn’t the only United Methodist leader who took issue to Sessions actions. More than 600 reverends and laypersons signed a formal complaint against the Attorney General. The complaint was addressed to church officials in Mobile, Alabama and Arlington, Virginia; two churches Sessions attends.

Part of the complaint reads:

“As members of the United Methodist Church, we deeply hope fora reconciling process that will help this long-time member of our connection step back from his harmful actionsand work to repair the damage he is currently causing to immigrants, particularly children and families.”

The document goes on to charge Sessions with violating the official United Methodist Code of Discipline, accusing his actions of promoting “child abuse, immorality, racial discrimination and the dissemination of doctrines.”

Sanders explained that officials and members within the United Methodist Church are allowed to cast formal complaints against actions taken by other church members.

“The goal is not to punish,” Sanders said. “The goal is to start a conversation, to pull people back and see if we can change their mind.”