From 1938 to 2018: The numbers keep dropping in college men’s gymnastics

April 17, 2018

Editor’s Note: This is part two of a four-part series on the disappearance of men’s gymnastics in the United States. The first part of the series was published on April 17, 2018, and can be found here.

Twenty one.

That’s the number of colleges that currently have a men’s gymnastics program in their college athletics department, according to the NCAA website. Compared to 130 Division I football schools and 351 Division I men’s basketball schools, that’s a small number that men’s gymnastics is facing in today’s world.

Oklahoma has been the face of men’s gymnastics for a number of years with three straight championships heading into this weekend’s championship in Chicago, Illinois. The Sooners have also been runners-up for the four years before those three years.

Oklahoma has been a dominant program that’s sent quite a few gymnasts to the U.S. National Team to compete in the Olympics.

Former Cedar Rapids Washington High School boy’s gymnastics coach Russ Telecky said he saw the number of men’s gymnastics programs in 1983 was 111 Division I programs and, now in 2018, only 21 colleges overall remain. In 1994, Iowa State dropped its men’s gymnastics program after winning three NCAA titles and two runner-up titles between the years of 1970 to 1974.

The drop of these men’s gymnastics programs in college are based around Title IX and budgeting in the athletics department. Penn State head coach Randy Jepson, Iowa head coach JD Reive and Nebraska head coach Chuck Chmelka all agreed that Title IX was one of the main factors that cut many college programs across the country.

On the other hand, these men’s gymnastics programs could be added again if athletics departments had the money in its budgets to add more sports to keep the percentages within requirements.

The only problem is that athletic departments don’t have the money yet.

“[Title IX] is an easy out. It’s a ‘we have to do this because the law says we have to do this,’” said Calli Sanders, Title IX coordinator with Iowa State athletics department. “It may have kept people from having to be the bad guy. It’s not that I’m making this financial decision to drop gymnastics, it’s because the law says we have to. So I think that’s sort of become the narrative.”

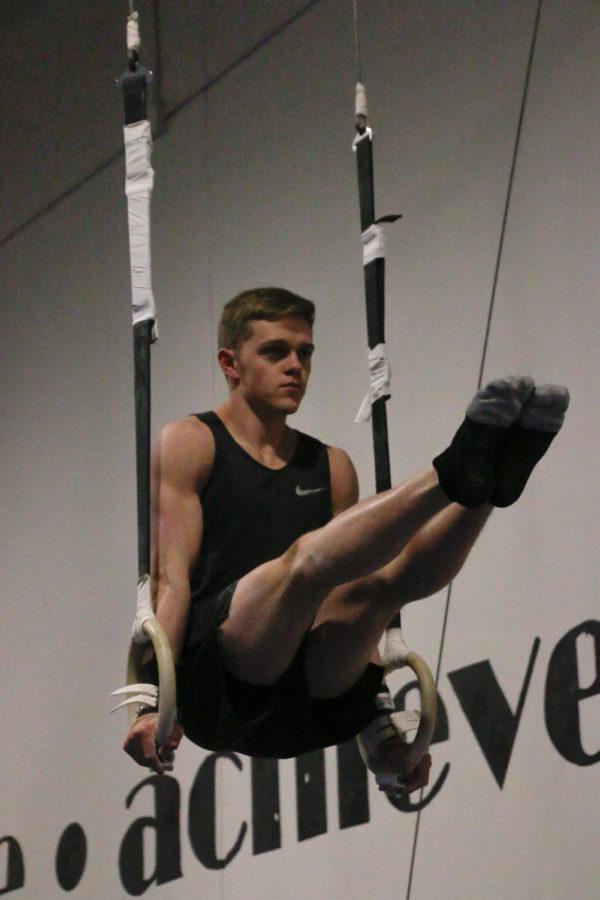

Even though men’s gymnastics and women’s gymnastics are similar sports regarding their titles, the equipment they use is very different. The only thing that’s similar between the two is the floor routines and the vault. The men use rings, a single high bar, pommel horse and parallel bars. The women have uneven bars and balance beam.

The equipment needed for men’s gymnastics is expensive because there are more events and each piece is specific. For example, a pommel horse costs around $3,500 and rings will run a team another $3,500. It all adds up in the end and it’s an expensive sport to operate, especially with only a select few men being a part of the team.

Due to Title IX, the majority of schools that still have a men’s team have very few scholarships and it’s rare to have a male gymnast joining a team on a full ride because the coaches need to split it up evenly.

Jepson said it’s hard to see one of his gymnasts that does all-around working hard to improve his skills and knowing he’s only receiving a small part of one scholarship. While on the other end, a gymnast on the women’s team is receiving a full-ride scholarship and competing in one or two events every competition. For him, it’s just hard to take in fully.

During Sanders’ time at Iowa State (she just celebrated 15 years on April 1), she’s never had to cut or add a program to Iowa State athletics. She said she always receives letters or emails from people regarding adding sports like men’s gymnastics, baseball and hockey, but none have become serious talks during her tenure.

The ability to add a sport, like men’s gymnastics, takes many steps besides coinciding with Title IX rules. If the sport were in serious discussions, Sanders said the athletic department would need to see if there’s any interest from the public about the sport.

She would also need to check the surrounding states to make sure recruiting can be easy around the Iowa area. Finally, she needs to check to make sure the athletics department budget says it can add a sport and not be in the negatives at the end of the fiscal year.

There have been many disputes in the sport of men’s gymnastics to keep certain programs in, with the latest being Temple. It wasn’t looking good for Temple to keep a Division I team because of budget reasons and overall interest in numbers. Luckily, the other 20 schools found fundraisers and ways to gain enough attraction and money to allow Temple to stay in the sports for this current school year.

Temple has a men’s gymnastics, but aren’t under the athletics department. Temple men’s gymnastics is self-sufficient and raises all their money on their own.

“We are always trying to gain more teams and more college gymnasts,” said Iowa gymnast Jake Brodarzon. “If we continue to encourage more schools to add a men’s gymnastics program, then the competition will increase.”

The benefit of having only 21 colleges is that the community within men’s gymnastics is closer. Many of these gymnasts have competed with each other or against each other in their private clubs prior to college.

Leading into each meet, the gymnasts are excited to see old teammates and friends that they’ve known for over five or 10 years.

“It’s fun to see everyone during meets and especially at the NCAA National Championship because you’re able to look back on memories,” said Iowa gymnast Mark Springett. “It’s hard not to know everyone because the sport of men’s gymnastics is so small in teams.”

That small community also makes it a challenge for coaches in these college programs because recruiting can be difficult. The recruiting process for men’s gymnastics is nothing like football or basketball or any other type of sport.

In most sports, recruits begin to be scouted in the early part of their high school years, but men’s gymnastics know recruits during their middle school and, sometimes, their elementary school years.

Reive said coaches hope a gymnast comes into their own private clubs with the potential of competing in college because the coach has a higher chance of having the gymnast on their team when they graduate high school.

If the gymnast isn’t in their private club, then they need to fight and show reasons why their program is stronger or competitive and has the opportunity to win a national championship.

The other big part to their recruiting process is summer camps hosted by the university. Each college men’s gymnastics program typically hosts a summer camp for a week or two to help build potential college gymnasts into an actual college gymnast.

The summer camp was a big part of Ames native Ben Eyles’ recruiting process. Eyles has been to many summer camps across the country and has seen his fair share of coaches before deciding on the University of Minnesota, but it’s always the same gymnasts at each of the camps.

Eyles said summer camps are a great opportunity to have coaches critique your routines and stay in contact for future meets. It was an integral part of Eyles’ recruiting, but summer camps aren’t the only way for coaches to recruit.

“You need to be the best gymnast you can be at these summer camps,” Eyles said. “It’s an opportunity to learn and grow as a gymnast, but you also need to showcase your talents before the end of it.”

Ultimately, the dream for most male gymnasts is to make it onto a college team. That’s their equivalent of making it to the NFL or MLB because there’s really no future after college for gymnastics.

The only thing past college for men’s gymnastics is the U.S. National Team and that consists of 12 men, so the odds of making the team are slim, but not impossible.

Chmelka and Telecky agree that it starts with high schools and private clubs to gain more numbers in men’s gymnastics, so the number of gymnasts can increase as well.

It’s not just private club instructors and high school coaches’ jobs to find more male gymnasts, it’s everyone’s job. The ability for college coaches to interact with middle school and high school gymnasts is a benefit in their recruiting process later on.

Overall, it’ll take the help of coaches, instructors and the actual gymnasts to bring this number up and keep the honor of representing the United States in the Olympics as the highest honor it can be.

“Ultimately, the dream is to make it on the national team for the United States and represent your country at the Olympic Games or World Championships,” said Nebraska gymnast Chris Stephenson. “It’s a hard spot to earn, but it’s what makes the sport such a fun sport to participate in.”