Story County SART team: Always there, always ready

SART locations

January 31, 2017

Trigger warning: This content uses language that may trigger sexual assault survivors.

Sexual assault is a complex and horrible issue. It is personal, it is heartbreaking and it is different in every case. But if we ever want to put an end to sexual assault, we have to stop letting its complexity get in our way.

This is the third story in a semester-long series where the Daily will publish a multitude of stories related to sexual assault, including discussions about various resources survivors can obtain if they are comfortable doing so.

— Emily Barske, editor in chief

As distant as it appeared on television, Mia Mayland never considered it possible to be a victim of sexual assault.

A consistent crime in shows like “Law and Order” — a favorite with the senior in child and family services — Mayland’s reality soon became just like the characters seen on the silver screen.

“We had been dating for a bit but broke up, and I didn’t like the way we had ended things,” Mayland, senior in child, adult and family services, said. “We were in Helser Hall together hanging out and drinking a bit. […] I eventually went to my room and he came with, and that’s where he sexually assaulted me.”

Mayland described the feeling after the assault as “freezing,” in that she felt numb to the world and those around her. Sitting with her best friend, Mayland sat for hours contemplating her options as well as trying to make sense of the occurrence.

It was with the support of her friends at Iowa State that Mayland eventually went to see the Assault Care Center Extending Shelter and Support, ACCESS, and finding helpful resources within nearly a dozen individual agencies that make up the Story County Sexual Assault Response Team (SART).

Not a single entity but rather a conglomerate of different teams and members, SART works in many ways to provide the tools needed to educate students and provide services to those who have been affected by sexual assaults.

Consisting of three health centers, one county attorney’s office and the ACCESS center, help for students often starts with contact to one of the six police departments within the county, or when the victim is most comfortable accessing services.

Anthony Greiter, officer for the ISU Police Department and community outreach member, stressed that every student who comes to the station is treated as an individual. Though a checklist walks victims through their many recovery and legal options, it is up to the person to decide how much help is needed.

“Everyone’s experiences are a little different, with different situations and different stages of recovery,” Greiter said. “Because we are so victim-centered, it’s my goal to give them all of the control.”

Control is a key aspect to much of SART, as victim confidentiality is enforced at nearly every turn of an assault report. A reporter can give as little information as their name and a location or go as far as seeking medical attention immediately.

By staying victim-centered, those who have been assaulted can progress through coping as fast or as slow as they feel fit. But because of police involvement, names of perpetrators must be reported to the to the university from ISU Police, but do not have to be publicly disclosed if the victim does not want to press charges.

This aspect also plays into the circumstances that surround an assault case. Because of the large amount of enforcement on college campuses involving drugs and alcohol, students may feel that a report will land them in jail if these substances were available at the time of the assault. However, there is is an amnesty clause in ISU’s sexual misconduct policy, which is the philosophy of not charging someone for making a report of sexual assault for additional minor crimes.

But Greiter hopes that this large barrier to reporting will not sway students from telling their stories if ready.

“Because we deal with alcohol consumption enforcement on campus, a victim might think, ‘Well, I was drinking so it’s my fault’ or ‘I shouldn’t have been doing that,’” Greiter said. “Not only do they have no bearing on what someone chose to do to you, but they provide more evidence against the perpetrator.”

RELATED CONTENT:

‘I am there with you’: A first-person experience of dealing with sexual assault

Separating gray: Different types of abuses

Initially uncomfortable with the idea of speaking to police, Mayland eventually found that their company provided valuable comfort.

“I was very uncomfortable during the talk with police, but I knew it was information they had to ask and would help,” Mayland said. “I ended up just driving around in an officer’s car talking, and that was surprisingly relaxing.”

Stating that students who are affected by sexual assaults often have difficulties remembering the attack, Greiter pointed to the many services offered by SART that are specifically designed to not only help perpetrator prosecution if requested but also provide a shoulder to lean on.

Steffani Simbric, SART coordinator for Story County, praised the extensive training received by all SART partners, including trained specialists who help gain information from the victim.

“We work to prove cases and not to disprove cases, and that’s where a lot of police departments who are trained go wrong,” Simbric said.

Tying into the ISU Police Department’s “Start by Believing” campaign, which encourages believing accusations instead of falsifying them, officers can work to help victims remember what they wish during a time of trauma.

This, along with free counseling, emboldens those who choose to speak out and offers them a chance to have a personal connection with a member of the community who can help during the coping process.

Given that evidence of a sexual assault can remain usable up to 120 hours after the attack, victims can take part in free medical exams and medication provided by the Iowa Sexual Assault Examination Payment Program.

Provided by the Thielen, Story County and Mary Greeley health centers, STD examinations and evidence kits are provided without charging a victim’s insurance company. Female patients can also be tested for pregnancy and be prescribed plan B medication if requested.

“We can create a record of the patient, which can be used in a court if a victim chooses to go down that road,” said Mary Raman, women’s health nurse practitioner at the Thielen Health Center. “Often we can get critical evidence for a case if a patient chooses to be examined and that’s often a big part of what we do.”

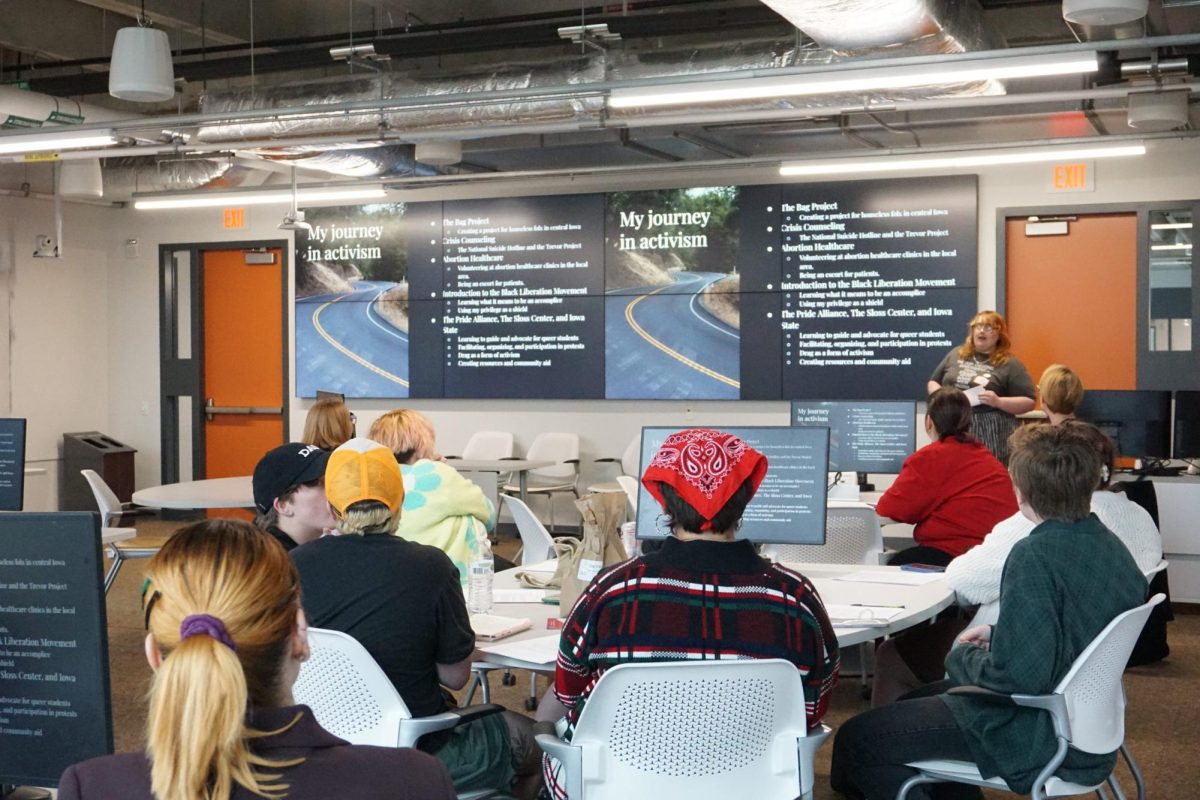

With several cases of campus sexual assault becoming more widely televised and talked about via mainstream media, ACCESS Campus Prevention and Outreach advocate Lori Allen sees hope for the current generation of young people to increase assault awareness.

“You’re seeing this generation begin to stray from typical gender binary rules, such as the dad being the breadwinner, and when you tear down those biases, you can begin to have conversations about sexuality more openly,” Allen said.

Allen cites the education of young people, particularly as college students, as the most important time to teach what acceptable sexual behavior looks like.

“Even if it is a first encounter, there should be enough communication to realize if both parties are in equal enjoyment,” Allen said. “If that isn’t the case, it shouldn’t be taken as an insult but should indicate that things shouldn’t escalate.”

As Mayland reflected on her own experience, she wanted to ensure that her perpetrator could still live out his life despite what he took from her.

“I didn’t want to ruin his life,” Mayland said. “He had a family that still loved him, he made a horrible decision, but I didn’t want it to be over for him.”

Sitting with her best friend the night of the encounter, unable to make a coherent decision on what she should do further, Mayland saw the impact of a strong support team.

“I’m happy right now in where both of our lives are at the moment,” Mayland said. “For me, it was a faster process because I’m resilient and I had that group of friends, family and my church. But for someone who doesn’t have those resources, the outcome may be different and take much longer.”

She hopes that students and the university will focus on education first, as the more open the public is to discussion, the further awareness can be taken.

“It all starts with education. If teens are having sex as early as 13, it can’t be too early,” Mayland said.