ISU researchers study galaxy collisions

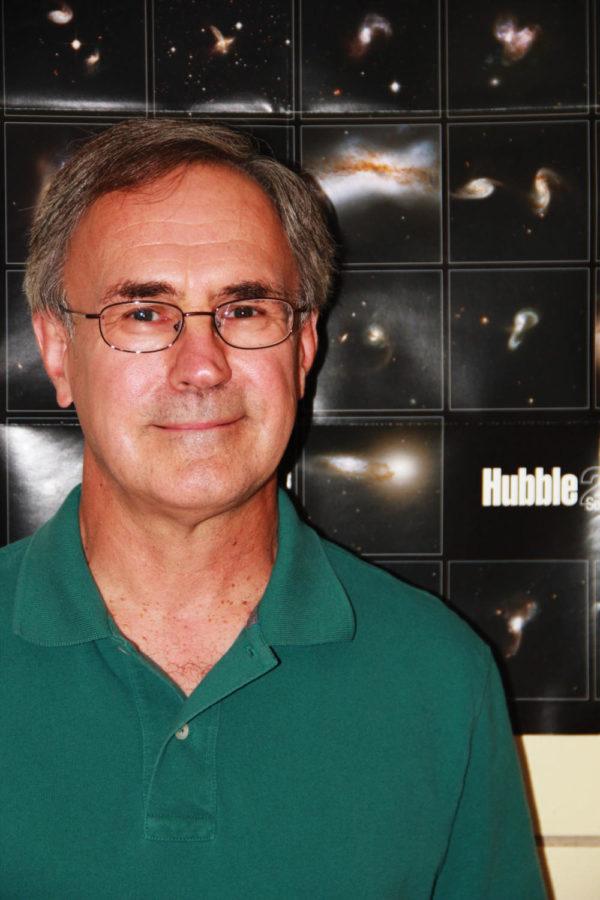

Photo: Emily Harmon/Iowa State Daily

Curtis Struck, professor in physics and astronomy, has been at Iowa State for 28 years. Struck teaches as well as researches, using information gathered from the Hubble Space Telescope.

April 5, 2016

When people think about galaxy collisions, the first thing that pops in their head may be super nova explosions or world-shattering catastrophes. It sounds like a scary subject, but researchers at Iowa State clear things up for us with their work understanding these large-scale events.

“My research is mostly modeling, mathematically and with the use of computers, collisions between galaxies,” said Curtis Struck, professor of physics and astronomy.

Struck has worked with models and simulations to get a better grasp on galaxy collisions. His research allows people to learn about what these collisions do on a universal scale.

Galaxies colliding does not create an explosive event like one may think. So much space exists between stars in two galaxies, which causes them to usually go through each other like ghosts.

“If our sun was the size of a basketball here in the U.S., the next nearest star would be in Beijing, China,” said Travis Yeager, graduate assistant in physics and astronomy.

With a lack of star collisions, it may be difficult to see why galaxy collisions are so special. The fact is they play a big role in galaxy and star formation.

“Galaxy collisions are one of the most important processes in the evolution of galaxies,” Struck said.

When two galaxies collide, they are moving at extremely high speeds. While their stars do not hit each other, they are still affected by each other’s gravity and their interstellar gasses mix. The result is a huge loss in energy, slower velocities and condensed interstellar gas.

Galaxies are giant formations, and when they slow while colliding, it is highly unlikely that they will ever get fast enough to escape each other. Unable to separate, the galaxies merge, forming a massive galaxy with pockets of condensed gas — hotspots for star formation.

“Some galaxies we observe have resulted from many galaxy collisions,” Yeager said. “There are galaxies we see that could only form from the result of several mergers, such as M-87, a huge elliptical galaxy.”

Understanding galaxy collisions is a step closer to uncovering the origins of all of the different formations in our universe, including our very own galaxy. With research geared toward uncovering the secrets of the massive universe we call home, one day some of the most difficult questions may have an answer.

“The impact of my research is on the way we view the universe,” Struck said. “What is our place in it and where did we come from? How did galaxies and planets build over time?”