Brase and Ward: Religion in fashion isn’t offensive

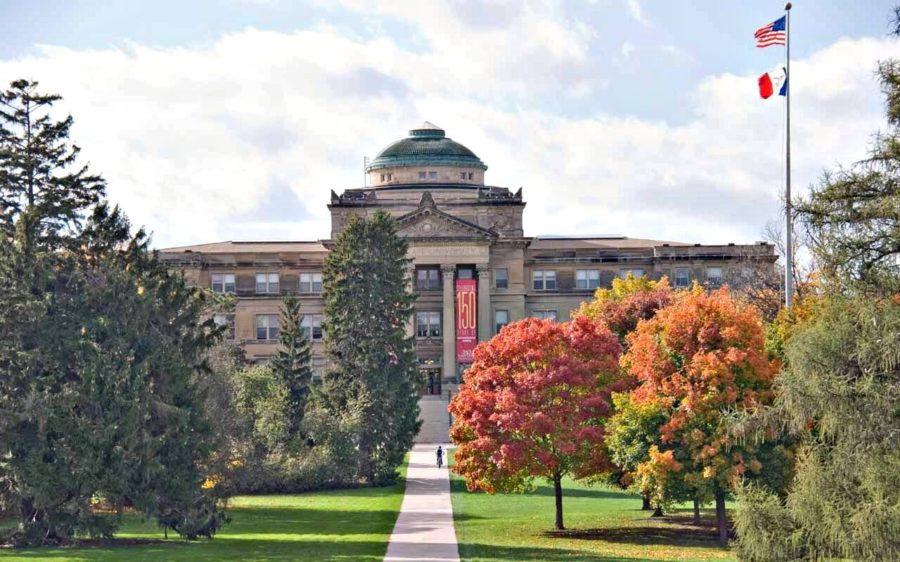

Emily Blobaum/Iowa State Daily

Religion in Fashion

February 10, 2016

Religious symbols, such as crosses, bindis, hennas and other styles, that are derived from other cultures or religions are being used for the purpose of fashion by people who do not always follow that religious or cultural belief.

Some may argue that this is an offensive act toward those who practice that religion or members of that culture. But the reality is using these symbols in fashion represents an artistic sense rather than a derogatory one.

When a designer takes a symbol that holds great meaning to various religions and cultures and uses it as a part of his or her designs, the meaning is no longer in its rawest form, but instead universal.

Crosses are part of the Christianity religion and stand for the death of Christ on the cross so to forgive everyone’s sins and allow them to go to heaven someday.

A Bindi is a jewel placed between the eyebrows on the forehead and is a symbol that belongs to the Hindu culture. Bindis can represent a married woman, the third eye, meaning they ward off bad luck, or culture.

Hennas belong to the Arab culture and represent good luck, health and sensuality. Women often get hennas to decorate their bodies for celebrations of luck, joy and beauty.

Some may say this tradition belongs within the culture and is only for those who believe in what the tradition stands for, but this is where culture and fashion meet.

I am guilty of getting a henna. To me, henna tattoos are beautiful and interesting and present an opportunity to learn about a culture unique to mine.

Most people who would choose to take on any of the styles listed above are not purposefully trying to insult those who follow that religion, but are looking at the style as the art the original designer transforms it into.

Religion is heavily reliant on symbols, which means those who follow any religion are protective of those symbols and care about the meaning behind them and how they are portrayed. But when these symbols are integrated into fashion, they become meaningful to everyone who can see the beauty in them.

I understand why people who follow a certain faith may feel disrespected when seeing others wearing a cross, bindi or henna for fun because the symbols have a deeper, more serious meaning than a fashion statement. But a line needs to be drawn between the religion itself and when it’s watered down for the purpose of fashion.

Sanaa Hamid, a Pakistani immigrant who lives in the United Kingdom, was interviewed on this topic in the Daily News. Hamid said if a Western person wears a Keffiyeh, a head scarf, then she is fashionable, but when Middle Eastern individuals wear one, they are labeled as terrorists. The issue with this is that judging anyone on the outside of a religion or culture for wearing a traditional symbol as fashion is no better than judging anyone who wears a symbol for the sake of their beliefs.

Religions have their own groups, but fashion is such a broad concept that belongs to everyone.

I think it’s fair for people to wear any kind of religious or cultural item, as long as they are not intentionally making fun of the religion or culture.

I understand that there is more to the religious aspect than looks, but if people want to put a jewel on their forehead, or wear a scarf around their head, let them. The people who wear items of religious connotations choose to do so because they think they look good and because a top designer took the symbol and made it into art, which then trickled down through the fashion trend system. Everyone has their own beliefs they follow, but fashion is a broader concept. Different sectors of religion come with different symbols, but when those symbols are integrated into fashion, they are then shared by the world.