A Harrison Tradition: Medicine

January 9, 2015

Tinsley Harrison’s family history was compiled of cotton farmers, but unlike other cotton farmers in Talladega, Alabama, the Harrison’s true profession was medicine.

The 351-paged bibliography not only tells the life of Doctor Tinsley, but also how his family left an impression on him—to follow his dreams.

As the seventh generation doctor in the family, Tinsley Harrison’s life was explained in detail throughout “Tinsley Harrison, M.D.: Teacher of Medicine,” a book written by his friend and mentee, James A. Pittman Jr., M.D.

At the age of 15, Tinsley was applying for college and had one in mind—Harvard. He was accepted, but his father could not afford it.

The aspiring lawyer went to Marion Institute, a military academy, in Marion, Alabama. Starting strong in college, he completed two years of school in only one year at the age of 16 in 1916.

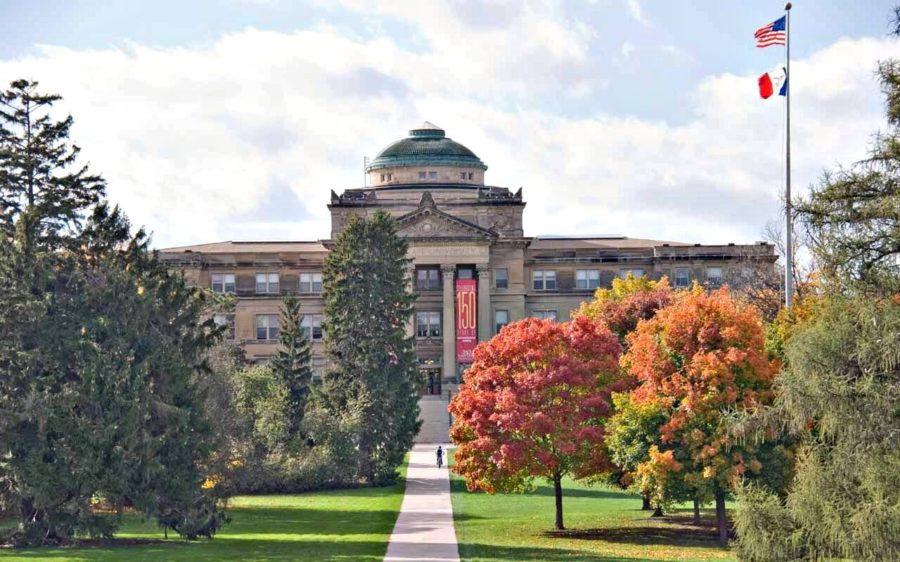

After graduating from Marion, a two-year college, Tinsley enrolled at the University of Michigan. Changing his mind from law, Tinsley majored in biology. In his third year at Michigan, he also began his first year in medical school while taking around 1,025 hours of extensive labs and lectures.

Attending the military academy helped him later in life when he decided to join the Navy at age 18, but still attended medical school at Michigan with the help of his father, a well-known doctor who pulled a few strings.

After only spending 83 days in the Navy, Tinsley did not qualify for the veteran’s benefits under the federal law of the United States because he was seven days short of the requirement of serving for 90 days. Unselfishly, Tinsley did not care because he did not think he deserved the benefits, since that was not his main focus. His focus was on medical studies.

In 1919, Tinsley received his Applied Baccalaureate degree from Michigan and wanted to continue his medical education. He earned his Doctor of Medicine degree at Johns Hopkins University on June 13, 1922 at the age of 22.

After graduation, Tinsley received an internship at Harvard Medical School, where he was an intern and an assistant resident. He started his residency in medicine at the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital in Boston and ended his senior residency at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Md. in 1924.

In 1925, he escalated into his career by becoming chief executive at Vanderbilt Hospital in Nashville, Tenn. and was hired to be on the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine faculty the next year.

During his time at Vanderbilt, he married and had four children to continue the Harrison family name in medicine.

By 1933, Tinsley published 54 papers. The majority of his works were written for American Journal of Physiology, the Archives of Internal Medicine and the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

He became the Chair of Internal Medicine at Bowman Gray Medical School in North Carolina in 1940 and moved to Winston-Salem, N.C. for a short time. Four years later, he and his family moved to Dallas, Texas, where Tinsley was the chairman and dean at Southwestern Medical College.

Tinsley published Principles of Internal Medicine in 1950 and became the chairman of the department of medicine, as well as dean and director of the division of cardiology at the University of Alabama. He moved back to his homeland in Birmingham.

Seven years later, he retired from being the chairman of the department of medicine because he believed he would not help the progress of the department if he overstayed his welcome as its leader. Instead, he became the chief of the division of cardiology at 57 years old.

Tinsley was honored as the Distinguished Professor by the University of Alabama Board of Trustees in 1964, but retired from being the cardiology director one year later. He was also named Veterans Administration Distinguished Physician in 1968.

Once Tinsley became a doctor, he did not selfishly keep his knowledge to himself, but wanted others to experience the gracious spark of patients’ eyes when helping them like his grandfathers did. His students would learn why he focused on close student-teacher bonds because that is how they would learn to treat their patients.

Diagnosed with a myocardial infarction, Tinsley quickly declined. Morphine was put into his IV and Doctor Tinsley passed away on Aug. 4, 1978.

Picturing the life of Tinsley’s family was not hard to comprehend because Mr. Pittman explained the difference between the generations of medicine.

While Tinsley’s forefathers were given farm animals as payment because their patients were penniless, Tinsley had more than a nickel to his name because of his success put forward by his obviously hard-working family.

This bibliography was well researched and detailed for not only Tinsley’s life, but his family. Although the book had plenty of detail, it was a bit dry. Trying to catch a reader’s eye with more excitement than specific facts would be ideal, but as I read, I could feel the emotions that Tinsley must have felt.

3/5