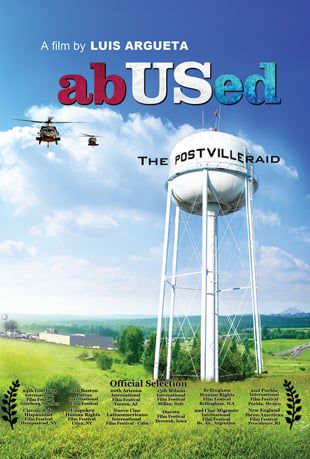

Parks Library Latinx film series highlights Postville raid

Parks Library showed the film “abUSed: The Postville Raid” by Luis Argueta on Thursday. The film focused on the story of the 2008 Postville raid and the workers it affected.

September 19, 2019

As part of Latinx Heritage Month, Parks Library is presenting four films pertaining to the Latinx experience in the United States. The first film, “abUSed: The Postville Raid” was shown on Thursday to a room of 11 people.

The film highlighted the Postville, Iowa, raid of 2008 and the injustices forced upon the undocumented workers detained due to the raid.

Two hours from Ames is the small town of Postville, called the “Hometown of the World” due to its meatpacking industry that drew in immigrants from all around the world.

The meatpacking plant was called Agriprocessors in 2008 and, unbeknownst to many outside of the community, it hired hundreds of undocumented workers.

On May 12, 2008, the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) division of the Department of Homeland Security executed the largest single raid of a workplace in U.S. history. They deployed 900 agents and even used helicopters.

“It was a sea of black, bulletproof vests and black hoods,” said one woman in the film as she described the raid.

According to the film, ICE arrested 389 workers, often verbally abusing the workers, calling them whores and bitches while pulling their hair and threatening to shoot and beat the workers if they ran.

Of those arrested included 290 Guatemalans, 93 Mexicans, two Israelis and four Ukrainians; 18 were juveniles.

One-fifth of Postville’s population disappeared in one day and another fifth went into hiding, fearing ICE. Houses sat empty and stores in the community shut their doors for good.

“It decimated the city, it decimated families,” said one woman in the film.

The workers were chained at the wrist and ankles and then loaded onto buses to be taken to the National Cattle Congress in Waterloo, a location where cattle were auctioned off. A makeshift court trial took place to arraign all 389 workers, who would later be sentenced.

Eighteen defense attorneys were assigned to the workers’ defense, with each attorney assigned 10 workers. These attorneys were initially refused entry to see the workers by ICE, who said there were no immigration cases happening — only criminal cases — so the attorneys were not needed.

Eventually the attorneys were let in, but very late at night, and they had almost no privacy with the workers. They had to work in makeshift cubicles made of plywood surrounded by fencing and were forced to talk with the workers, oftentimes with ICE guards in the cubicles.

The workers were held in a large warehouse-style building with cots, which was never certified as a detention center by the United States Department of Justice due to the deplorable conditions the workers stayed in. ICE televised lies about their conditions, showing images of many cots, board games and even access to computers. It was later found out the ICE guards were the only ones with access to the computers and games.

Back in Postville, children and family members not detained during the raid flocked to a church for sanctuary where they were welcomed and immediately tried to find out who was taken and if they could contact them. There was an ICE information number the families called, but they were met with resistance and were told either nothing or very little about their loved ones.

Many children were left without family members to take care of them, as both parents had been detained.

Even though the trials were technically public, ICE tried to refuse admittance to the trials by heavily grilling each person as to why they wanted in and if they had any relation to the workers being convicted.

Not one of the 389 workers were charged with illegal immigration or anything related to immigration, but instead were charged with identity theft for owning fake social security cards. Many were coerced into signing a plea agreement. At least two mothers lied and said they did not have children, hoping to protect them.

The immigrant workers, most of them without prior criminal records, were offered a plea agreement in exchange for a guilty plea to lesser charges. 297 accepted the agreement and pleaded guilty to document fraud.

In an expedited procedure known as “fast track,” hearings were scheduled over the course of the following three days. The judges took guilty pleas from the defendants in groups of ten and sentenced them immediately, five at a time. The workers were bound by handcuffs at the wrists as well as chains from their upper torso to their ankles.

“These were immigration cases disguised as criminal cases,” said a man in the film.

Over 300 of the workers were convicted on the document fraud charges within four days as part of a plea bargain. Two-hundred-and-ninety-seven of them served a five-month prison sentence before being deported, including the two women who lied about having children — they have not seen them since 2008.

Some of the workers were released with GPS tracking bracelets on their ankles and sent back to Postville to care for their children. Due to the tracking bracelets, they could not get jobs or even go to the doctor, which greatly decreased the care they could give to the children they were released to take care of.

Forty-one of the arrested workers, many of whom were the workers with GPS trackers, were allowed to remain in the U.S., granted with a special U-visa. These workers suffered violent abuse at the hands of Agriprocessors.

While processing the workers, some troubling information was found out about Agriprocessors.

It was revealed the meatpacking plant had been employing minors as young as 14 in dangerous conditions. The undocumented workers of all ages received no medical benefits and little to no safety training, which caused serious injuries. Also, the workers would sometimes work 60 hours worth of overtime but not get paid for barely any of it.

Agriprocessors was fined $9.9 million and the owner, Aaron Rubashkin, and his sons Sholom Rubashkin and Heshy Rubashkin were convicted of immigration and labor law violations. Both Aaron Rubashkin and Sholom Rubashkin were initially charged with 9,311 counts of child labor law violation, for which they could have faced over 700 years in prison if found guilty.

All charges against Aaron were dropped right before the trial was scheduled to begin. After a five-week trial, Sholom was acquitted on all charges of violating child labor laws. His case was later completely expunged from Iowa state records.

Financial irregularities brought to light by the raid and subsequent investigations led to a conviction of the plant’s chief executive Sholom on bank fraud and related charges. He was sentenced to 27 years in prison, but on December 20, 2017, President Trump commuted his sentence to time served and his trial on immigration charges was canceled.

After the film, there was a discussion among attendees facilitated by Megan Myers, assistant professor for world languages and cultures.

One attendee connected the film and the conditions the workers were held in to the current immigrant holding facilities in the southern United States.

The next film screening in the series will take place at 6 p.m. Thursday in Parks Library, room 198.