First black graduate changes agriculture

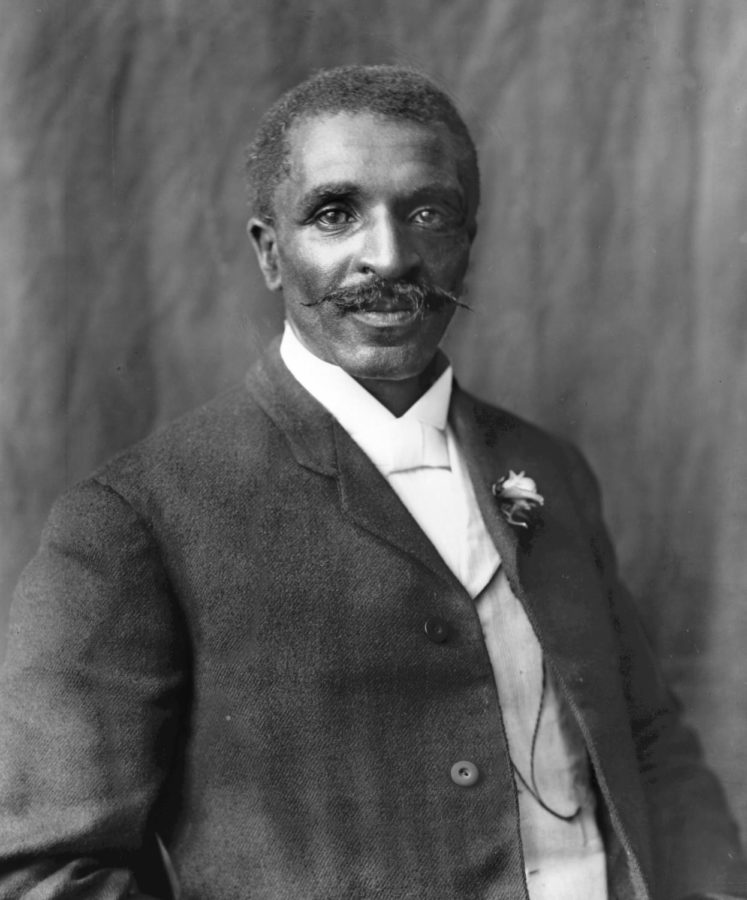

George Washington Carver, the son of slaves, is one of the most famous Iowa State alumni. Most known for his work with peanuts, Carver also helped run the school’s greenhouse.

June 24, 2014

Editor’s note: In celebration of the 150th anniversary of our city, the Daily will highlight prominent figures, places and events in Ames’ history each week.

Born a slave in Missouri, George Washington Carver was raised by his former masters, Moses and Susan Carver, as a son after his parents died. The exact date of Carver’s birth is unknown, but it is estimated to be in 1864 or 1865.

The Carvers encouraged him to pursue his intellectual interests. When Carver arrived in Iowa in 1890, it wasn’t crops — for which he is known — that brought him. It was music.

After being rejected by Highland College in Highland, Kan., in 1886 for being black, Carver homesteaded a claim in Ness County, Kan. He worked odd jobs while cultivating his love for plants, keeping a small garden with trees, shrubbery and crops.

After obtaining a $300 loan for education, his first stop in the state of Iowa was Simpson College in Indianola in 1890. The school was endowed by Matthew Simpson, an equal rights activist who had been friends with Abraham Lincoln. Carver was accepted freely. There he briefly turned to the arts and the piano, but new ways to approach agriculture would prove to be his calling.

When his teacher, Etta Budd, noticed that Carver excelled at painting nature, she encouraged him to study botany instead. His next stop was the Iowa Agricultural College and Model Farm — now known as Iowa State University — where Budd’s father was an agricultural professor. He arrived in 1891.

He eventually earned a master’s degree from Iowa Agricultural College, performing experiments with mycology — the study of fungi — and plant pathology. He knew well the struggles of poor farmers, especially poor black farmers, and at Iowa Agricultural College he discovered a fertile ground for his attempts to help them better their lives, according to a paper written by Carver.

Peanuts would be a focus for Carver. He believed that, if used correctly, the protein-rich food could not only become a more reliable commercial crop but could also provide a food source for poor farming families.

In 1916, he used the knowledge he’d accrued through his studies at Iowa Agricultural College and the Tuskegee Institute to publish a bulletin offering 105 uses for the crop. During his studies, he also worked with soybeans and sweet potatoes, all as substitutes for cotton. The over-reliance on cotton was seriously damaging southern farmers’ economy by the time Carver arrived in Iowa.

Despite a large study load, he also found time to become a captain of the student battalion in the National Guard. He was a member of the debate team, the German club and the art club as well as an athletic trainer for the football team.

Carver’s impact on Iowa State didn’t begin and end with agricultural advances. Spurred by the advice of a childhood mentor who told him to “give your learning back to the people,” Carver, who became the school’s first black graduate, also became its first black teacher. He directed the school’s botanical greenhouse and traveled throughout the state, delivering botany lectures.

However, he wasn’t free from discrimination at Iowa State. While a student, he was forced to sleep in an old office rather than the dormitories and eat in the basement with the employees. He left the college in 1896 for the Tuskegee Institute, and, despite discrimination, he said, “I have no words to adequately express my impressions of dear old [Iowa Agricultural College]. All I am, and all I hope to be, I owe in a very large measure to this blessed institution.”

Carver died in 1943. His legacy of both developing new agricultural practices and freely giving his knowledge to others has earned him a place in history. Carver himself may have summed up his accomplishments perfectly when he said, “No individual has any right to come into the world and go out of it without leaving behind him distinct and legitimate reasons for having passed through it.”