Professor helps discover new kind of misaligned solar system

Steven Kawaler, professor of physics and astronomy has recently contributed to the discovery of a new kind of misaligned solar system named Kepler-56, a red giant star that is orbited by two smaller inner planets and one large outer planet.

October 27, 2013

An ISU professor has recently contributed to the discovery of a new kind of misaligned solar system.

Steven Kawaler, professor of physics and astronomy, partnered with Daniel Huber, who is doing post-doctoral research at the NASA Ames Research Center in California.

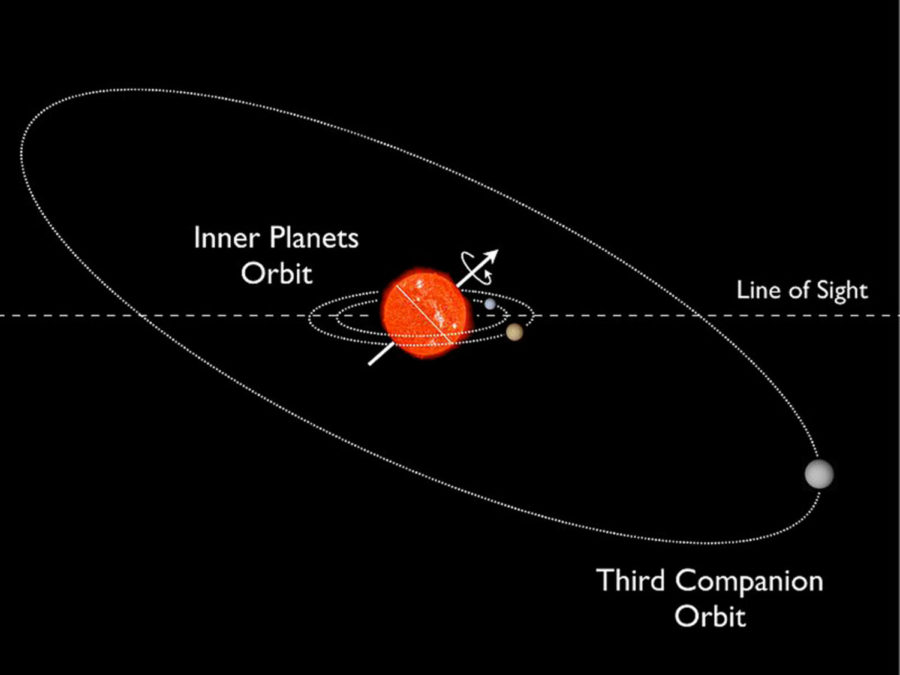

The system that they discovered, Kepler-56, is a red giant star orbited by three planets – two small inner planets and one massive outer planet. Because solar systems start out as a flat, whirling disc of gas and dust, most planets have flat orbits perpendicular to the axis of the star’s rotation.

“The final configuration of a planetary system remembers that it was born in a disc,” said Massimo Marengo, associate professor of physics and astronomy. “So the planets tend to remain in the same plane, like the planets of the solar system.”

However, this system does not follow that rule. None of its planets have a flat orbit. The two small planets orbit in one plane, and the massive planet orbits in another.

The astronomers first realized that something was different about this system when they studied the oscillations of the star’s light. They can use these oscillations to detect the angle of the stars rotation relative to the Earth.

“It’s fairly complex vibrations — like a bell. When you ring a bell it vibrates in all sorts of ways. Stars do the same thing,” Kawaler said. “If you listen to a bell from one direction it sounds different than from another direction.”

They discovered that the star’s axis of rotation was not angled directly at Earth or directly perpendicular to it. This didn’t make any sense, because they could see planets orbiting between the star and planet Earth, Kawaler said.

When a planet orbits a star, it blocks some of the light from that star. We can usually observe this — and thus detect planets — only when the star’s equator is facing Earth, because most planets orbit around the equator. The astronomers detected the two smaller planets through that method.

“That was a mystery. Here’s a star that has planets, orbiting in what we thought was the equatorial plane which had to be pointing at us, but the oscillations tell us that the star’s pointing [another] way,” Kawaler said. “Only in very few systems do you see that misalignment. In almost all cases where that happens there is a big fat planet that’s really close to the star, and in this case they’re little tiny planets.”

While they were writing a paper on the solar system, Huber found other papers that offered an explanation for the tilt of the planet’s orbit. Computer models have shown that if a system has a massive planet far out, it can sustain tilted orbits and remain well behaved.

Other members of the team had access to large telescopes in Hawaii. They found the massive outer planet by observing how the mass of that planet pulled at the host star.

The research on this particular solar system has come to a halt because the Kepler telescope can no longer focus on that area of the sky. However, the astronomers can still observe the massive outer planet, which was detected from the ground.

Now, the team is taking a statistical look at other planetary systems to better understand the planet formation process.

“We’re now looking at these things statistically. We’re doing a fairly detailed first look and then moving onto something else, trying to find families,” Kawaler said. “We’re looking at twenty new systems, to see if we find anything interesting.”