Gross: Classics should be taught to an appropriate age

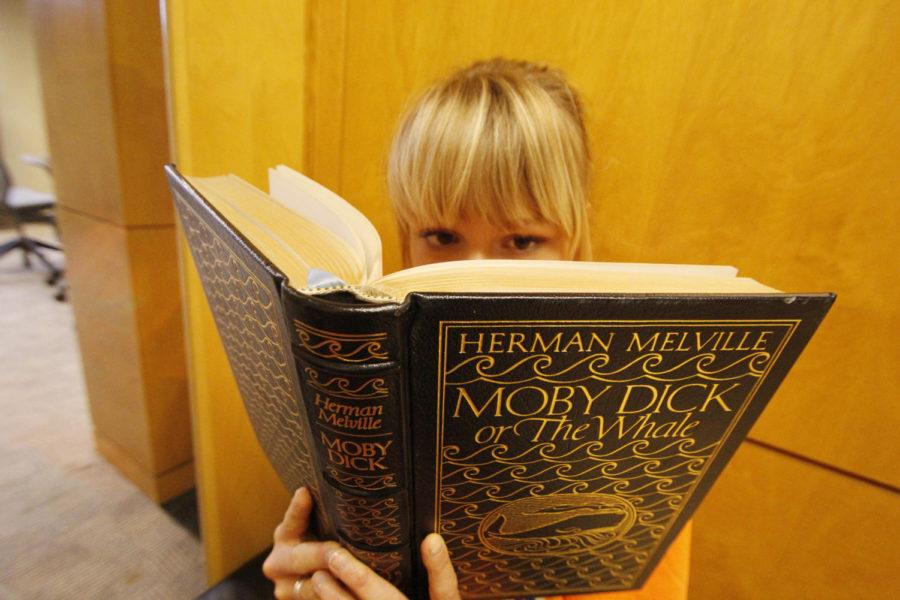

Jonathan Krueger/Iowa State Daily

Classic novels have lost relevance for high school students due to the fact that they can’t relate to what occurs in the books of different time eras.

September 11, 2013

In our modern form of education, classic literature is inescapable. Whether you dream of being a teacher, a banker or a veterinarian, it is hard to get through high school without encountering Salinger, Dickens or Whitman in an English class.

Readers of Oscar Wilde will praise his witty prose and the commentary he provides on high society in the late 1800s. Shakespeare-lovers expound on the fluidity of his verse and the romance of his language. And nowhere is the 1920s fear of socialism more brilliantly illustrated than in George Orwell’s “1984.”

Beauty of language, cunningness of rhetoric style and strength of historical commentary are what make these and a myriad of other books “classic.” And certainly these works deserve a place in the vast world of academia.

However, I am unsure if that place is in middle and high school classrooms.

When first approached with Harper Lee’s “To Kill a Mockingbird” at the young age of 12, I didn’t know what I was getting in to. I feel it’s safe to say my classmates, few of which were nearly as voracious in their reading as I was, were even more helpless.

Young readers might understand the words on a page enough to interpret a book sentence by sentence. The main storyline is not lost on our youth. Nearly anyone can see clearly enough that the plot of “Lord of the Flies” is, simply put, a group of stranded kids whose attempts at organization fall into chaotic horror.

However, the larger social and psychological connotations might not be apparent to individuals between the ages of 12 and 18. Even with the careful guidance of skilled teachers, students are often not so much lead as they are dragged to the “deeper meanings” of literature. The majority of middle school or high school students simply aren’t the right audience for “classic” literature.

This is an argument that has been posed before, but the more common logic behind it is that antiquated classics just cannot be related to by young adults, as part of a more modern generation. However, even now in the 21st century, there are issues, inequalities, social injustices and events with which we can relate to books that seem obsolete.

We might not face the level of racism portrayed in “To Kill a Mockingbird” in America, but certainly there are prejudices on a global, if not national, scale to which Lee’s work can be compared.

Yes, high school students are unable to relate to certain classic texts. But it is not because we live in an age that is too far removed from yesteryear to even imagine it. We as a society have not come so far that the dystopian fears of Orwell’s works or Fitzgerald’s caution against excess are no longer applicable.

As phrased by author and journalist Italo Calvino: “A classic is a book that has never finished what it has to say.”

Defined as such, a classic never loses its relevance. Readers in present and future generations can glean applicable and pertinent knowledge from the pages of Jane Austen’s “Pride and Prejudice.”

So, what makes high school students an inappropriate audience for classic literature, if not the aged themes of the books? Put simply, it’s the un-aged status of the readers.

High school students are too young to really appreciate classics. That is not to say that they are not smart enough; many young adults’ intellects peak at young ages. It is simply the majority of high school students — sheltered by loving parents and living at home for the entirety of their life — are not worldly enough to understand the messages hidden between the lines in classic literature.

A classic has “never finished what it has to say,” and what it has to say is usually something profound about the state of society, government or the entire world. High school students, as the fledgling readers and academics that they are, cannot hope to see the whole vast truths contained in the pages of our time-tested literature.

There are books, both old and new, that are more digestible and more relevant to a younger readership, not through simplicity of language or style but simplicity of themes.

The reason why our classics are so honored is because they contain messages both great and terrible. As such, they deserve a place in academia, and should be heavily studied by academics of all fields.

But that study is made inane when it is started too early. Rather than destroying our youth’s taste for the classics by force-feeding them, we need to have the patience to teach them when the time is truly right.