Drought affects ethanol mandate

Graphic: Katherine Klingseis, [email protected]

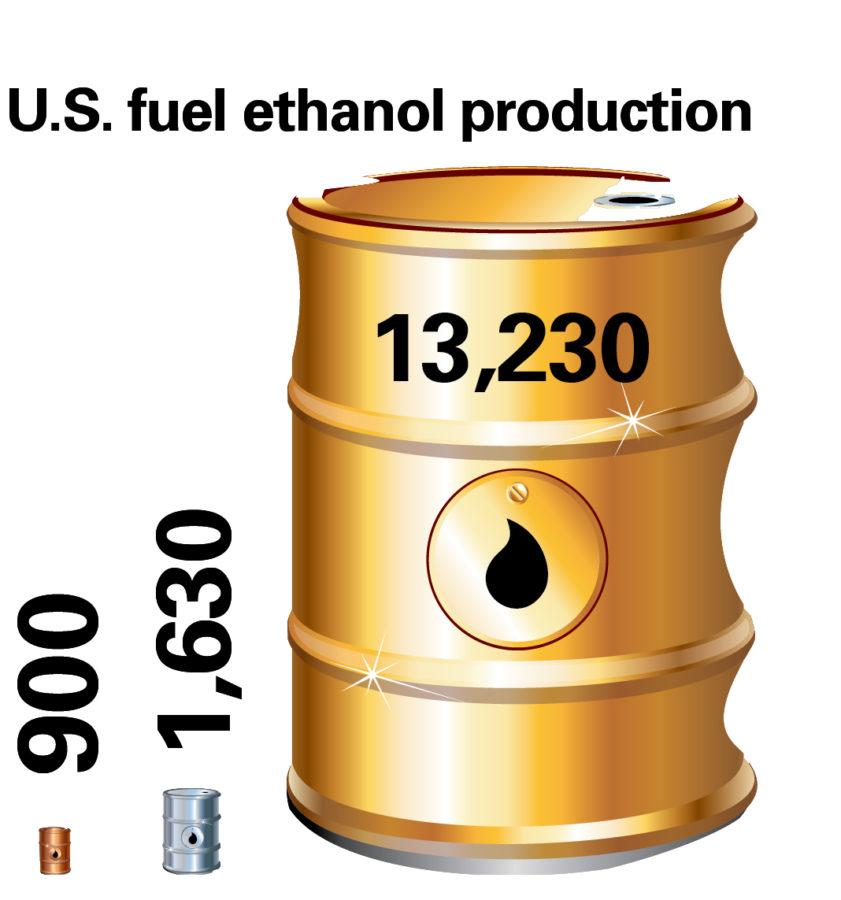

The U.S. fuel ethanol production increased from 900 gallons in 1990 to 13,230 gallons in 2012, according to the Renewable Fuels Association.

September 13, 2012

During the worst agricultural drought since 1988, people were worried not about filling up their tanks but, rather, putting food on the table.

An important question arises of why corn is still being used for ethanol production rather than food.

“Corn ethanol production in the U.S. has grown exponentially,” said Tristan Brown, graduate student in biorenewable resources and technology. “The biorenewable energy industry is producing more corn ethanol today than ever imagined.”

All the biofuels being produced are corn ethanol. When drought hits, demand increases and corn prices rise.

The federal government passed the Renewable Fuel Standard requiring that by 2022, 50 percent of all ethanol produced comes from a noncorn source.

Brown said the fuel standard provides a financial incentive for the different types of biofuel production.

This mandate essentially seeks to gradually replace corn ethanol with biofuels produced from other biomass sources and reduce the industry’s dependence on corn as the main crop.

Brown said biomass is basically three things: carbon, hydrogen and oxygen.

“What you can do is take the sugars that you would ferment into alcohol into ethanol, or treat them, get rid of the oxygen and get left with hydrogen and carbon,” Brown said.

The extracted elements can then be used to create drop-in biofuels, hydrocarbons produced from biomass. These biofuels can be placed immediately as an alternative fuel for cars without being blended with regular fossil fuel gasoline.

Corn stover, the remaining portion of the corn stock that is left after the corn grain has been harvested, is another possible candidate for making renewable fuels.

Brown said corn stover can be heated to extreme temperatures, 300 to 1,000 C, through a process called pyrolysis.

The resulting liquid can then be treated to remove the oxygen, leaving behind hydrocarbons that can be used to produce drop-in biofuels.

Dermot Hayes, professor of agricultural economics, explained that through pyrolysis, stover produces bio-oil and biochar.

Bio-oil can then be turned into butanol, which is the drop-in biofuel from agriculture.

The char is added benefit.

“Char can be used to help farmers, because it improves soil moisture capacity,” Hayes said.

Corn is part of everyday life for people living in the Midwest. Beyond the cities, corn fields cover the landscape. One can cruise the countryside for miles on end through oceans of green in the summer and golden brown in the fall.

For many, corn is a source of food, fuel and income; a lifestyle. Iowans know this fact to be especially true. However, Brown said he noticed Americans living on the coasts share a different perspective.

“When I was out east a few years ago, I noticed something that was really weird at first,” he said. “I drove out to Pennsylvania. The signs were advertising the fact that they didn’t sell ethanol.”

It was the exact opposite. They were boasting with signs saying “We do not blend ethanol” or “No ethanol sold here.”

“If you’re from Iowa, you’ve seen the gas stations here all advertise the fact that they sell ethanol,” Brown said.

Brown said that on the East and West coasts, people have an impression that ethanol starves people and causes Brazilian rainforest destruction.

Based on research conducted on Iowa State’s campus in Heady Hall in 2008, the theory “Indirect Land Use” hypothesized that raising the price of corn here caused the people in Brazil to start growing corn; destroying rainforests for farmland.

“They said that enormous quantities of rain forests were being destroyed because of corn ethanol production,” Brown said. “Just last year, the same researchers went back, reran their numbers and found that their initial estimates were completely off base. They had overestimated by about five to 10 times.”

The damage had already been done.

This research was published in Science, the largest science journal in the world.

Brown said that the media quickly noticed. For the next three years, headlines ran describing how corn ethanol production destroyed rain forests.

“An attempt was made to publish an update in the same journal, but the journal wouldn’t publish it because they didn’t want the negative attention,” Brown said.

The future of renewable fuels lies within a variety of crops, not just corn alone.

“I get this notion that the drought has given ethanol a really bad name because everyone thinks that ethanol has something to do with the drought driving prices up so high,” Brown said. “These signs don’t say ‘We don’t sell corn ethanol here,’” Brown said. “They just say ‘We don’t sell ethanol.’ They don’t specify cellulosic ethanol.”