Belding: Judicial review protects Americans from excesses of politics

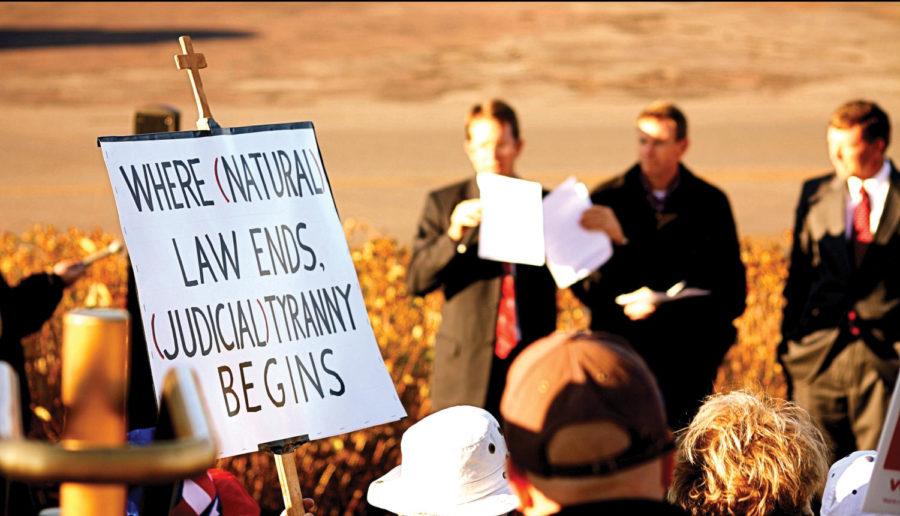

Photo courtesy of Flickr/Phil Roeder

Opinion: Judicial Review

August 28, 2012

In my previous column, I argued the renewed efforts of social conservatives such as Bob Vander Plaats, together with the directive of Republican Party of Iowa Chairman A.J. Spiker, show a willful ignorance as to the validity of judicial review.

Today I suggest, additionally, that such a practice is indispensable. Judicial review safeguards the freedoms and liberties of all Americans; each of us has an equal likelihood of being assisted by the practice. Tyranny of the majority is a very real problem, and our constitutional system was designed to keep it at bay. Judicial review by an active judiciary is an integral part of that system.

For such an exposition we must look largely to the writings of Alexander Hamilton, principal author of the Federalist Papers, a project on which he collaborated with John Jay and James Madison, the man credited with writing the Constitution in 1787.

Provisions such as the Bill of Rights would be meaningless without a judiciary capable of reconciling them with laws passed by the legislature. Hamilton wrote in Federalist 78: “Specified exceptions to the legislative authority … can be preserved in practice no other way than through the medium of courts of justice, whose duty it must be to declare all acts contrary to the manifest tenor of the Constitution void. Without this, all the reservations of particular rights or privileges would amount to nothing.”

The practice of judicial review exercised an important balancing function; “the courts were designed … to keep [the legislature] within the limits assigned to their authority.” Judicial review would keep excesses of power to a minimum: “No legislative act … contrary to the Constitution, is valid. To deny this would be to affirm that … men acting by virtue of powers may do not only what their powers do not authorize, but what they forbid,” Hamilton wrote.

Compared to the executive and legislative branches of government, which hold the proverbial power of the sword and purse and prescribe “the rules by which the duties and rights of every citizen are to be regulated,” the courts are a passive agent of government. Hamilton explained: “The judiciary, on the contrary, has no influence over either the sword or the purse; no direction either of the strength or of the wealth of the society, and can take no active resolution whatever. It may truly be said to have neither force nor will but merely judgment; and must ultimately depend upon the aid of the executive arm even for the efficacy of its judgments.”

So to the extent that the Iowa Supreme Court judges “legislated from the bench” in the Varnum v. Brien decision to allow same-sex marriage in Iowa, they did so because they struck down a limitation on marriage, not by rewriting the law.

Without actual policymaking powers, the courts’ role is to keep within constitutional bounds the policy that is made by executives and legislators. That role is important. Hamilton’s insight was that “in a monarchy it is an excellent barrier to the despotism of a prince; in a republic it is a no less excellent barrier to the encroachments and oppressions of the representative body. And it is the best expedient which can be devised in any government to secure a steady, upright and impartial administration of the laws.”

Prioritizing the Constitution over laws enacted either directly by the people through referendums or through their representatives using the legislative process, will safeguard the actual will of the people. The power of judicial review, Hamilton wrote, “only supposes that the power of the people is superior to both and that where the will of the legislature, declared in its statutes, stand in opposition to that of the people, declared in the Constitution, the judges ought to be governed by the latter rather than the former.”

Really, the issue comes down to allowing interested parties to sit on their own juries. Hamilton said as much in explaining the judiciary, in Federalist 80: “No man ought certainly to be a judge in his own cause, or in any cause in respect to which he has the least interest or bias.”

Hamilton was not alone in decrying biased judging; his partner on the Federalist Papers project, James Madison, had made a similar argument months earlier. He did so in a now-famous essay, Federalist 10, in which he examined the causes and remedies for factions in politics. He wrote: “No man is allowed to be a judge in his own cause because his interest would certainly bias his judgment, and, not improbably, corrupt his integrity. With equal, nay with greater reason, a body of men are unfit to be both judges and parties at the same time.”

Hamilton expected, from a combination of judicial independence and the judiciary’s power of review, an “inflexible and uniform adherence to the rights of the Constitution, and of individuals.” They would do so because courts reconcile the results of politics (law) with the Constitution. Leaving that responsibility to the political branches of government, which Vander Plaats and Spiker seem to be suggesting we do, would leave judgment in the hands of an inherently biased group.

There are legitimate reasons for rejecting judges. Fulfilling one corner of the triangle that is a balanced government is not one of them.