Timberlake: Seek danger and adventure in life

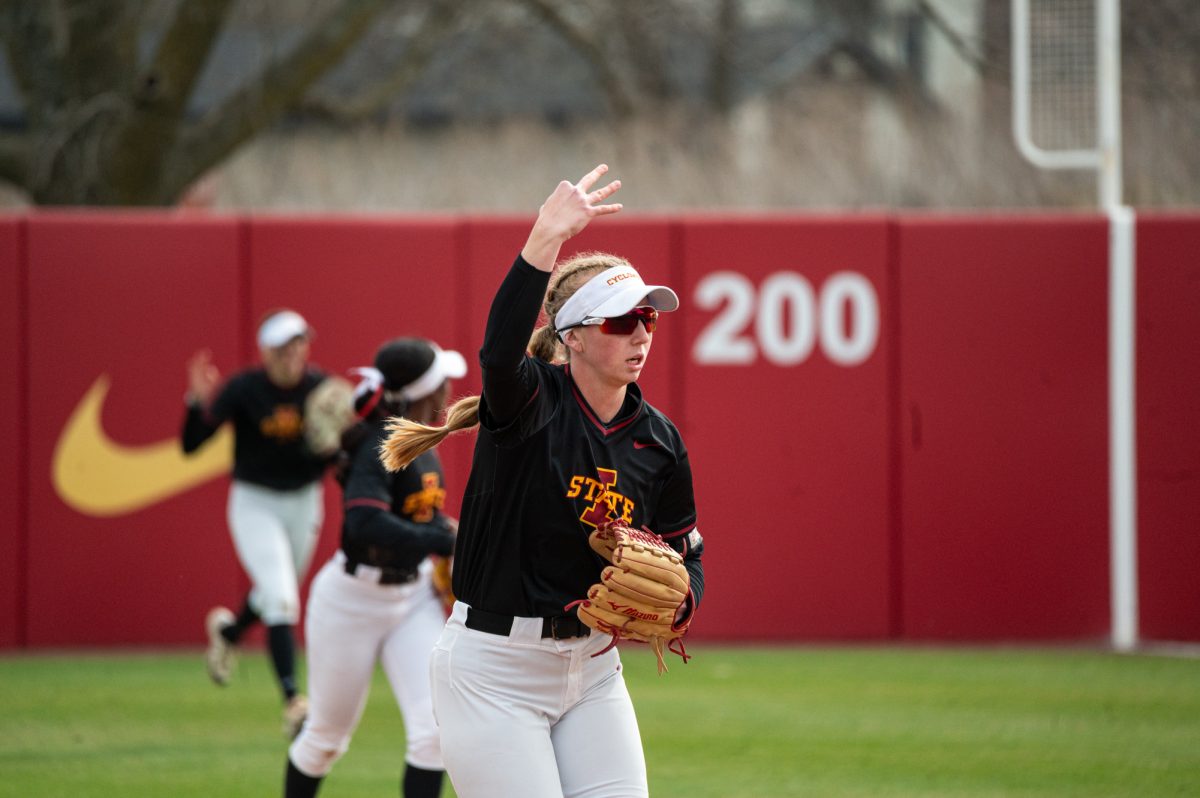

Photo courtesy of Ian Timberlake

Opinion: Mt. Rainier

August 23, 2012

I was born to die, and so were you. Death is the inexorable disease inseminated upon conception. Fear of death is more compelling than compassion, love, hate, envy and hope.

Value: Where do you think it comes from? Is it from family? Friends? How about religion? Maybe all three. While these may be very important to a lot of people, I could feasibly generate a valuable life even after expelling all three (or in my case just two).

Universally, life value comes from time. Time is the currency of life — thus, it is because we die that makes life unimaginably worth living.

The adventurers of the world have become more aware of their time spent on Earth. Be it the Alaskan kayaker, the Amazon jungle trekker, the Everest summiteer or the planetary circumnavigator — they all know about imminent death.

Three years ago I committed to attempting the “7-summits” — the tallest mountain on each continent: Aconcagua, Carstensz, Denali, Elbrus, Everest, Kilimanjaro and Vinson Massif. This was a goal of mine in my desire to chase the dangerous.

This summer I successfully summited Mt. Rainier in the state of Washington. Standing in at 14,410 feet, it is the most prominent mountain in the contiguous states and a rite of passage for mountaineers in the world. In late May, I attempted the mountain and was snowed in for five days and never was able to summit. Rescues were made and a ranger even lost his life during those (at the time) winter conditions. Early August I returned, blessed with near perfect weather and summited in two days time.

I have relatively high control over what happens to me on a mountain such as Rainier, aside from avalanches and falls (which has a level of risk analysis). I, however, have little control over natural disasters, violence, vehicular accidents and disease, among other things. It’s rather disconcerting that the act of fearing death simultaneously brings bore to the commons. Tell me this: Would you just as soon prefer a death by death-bed heaving up your own lungs and drowning in body fluid, as death by blowing off a mountain? I believe a serious judgment of character can be made by your answer. Only a boring person would prefer the former; and I claim that statement.

On May 29, 1953, Edmund Hillary and Sherpa Tenzing Norgay became the first team to successfully make a confirmed summit of Mt. Everest. Nearly 30 years earlier and many deaths accumulated, mountaineer George Mallory was asked by a reporter: “Why climb Everest?” Mallory replied: “Because it’s there.”

Mallory also said: “What we get from this adventure is just sheer joy. And joy is, after all, the end of life. We do not live to eat and make money. We eat and make money to be able to live. That is what life means and what life is for.” Mallory soon perished somewhere near the summit of the 29,029 foot mountain.

Mt. Rainier is just a training wheel in my quest for the “seven summits,” including Everest. Why you too should seek the vulnerable is because it’s only when you lay eyes on fatal departure that you truly feel alive. Experiences and knowledge reveal themselves where they wouldn’t otherwise. Views are made that humans aren’t supposed to make, and as Henry David Thoreau puts it in “Walden”: “I want[ed] to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life, to live so sturdily and Spartan-like as to put to rout all that was not life.”

Every person has stakes in the game of life. Until you understand that your life value only exists because you will eventually die, then you might as well not have a purpose. Given the option to live forever, I would politely decline. It would suck the value out of the actual living part of existing by removing what might be considered difficult to do within the span of a lifetime.

With unlimited time, there’s the possibility for unlimited achievement and therefore all respect would be expunged. The old adage remains true: “With great risk comes great reward.”

Death is more connected to life than anything else, so live it up, and make yourself worth something — use the time such that when you take your last breath, you’ll be able to look back and say: “Yes, that was worth it.”