Belding: Damage can give character, not just harm

Photo: Andrus Nesbitt/Iowa State Daily

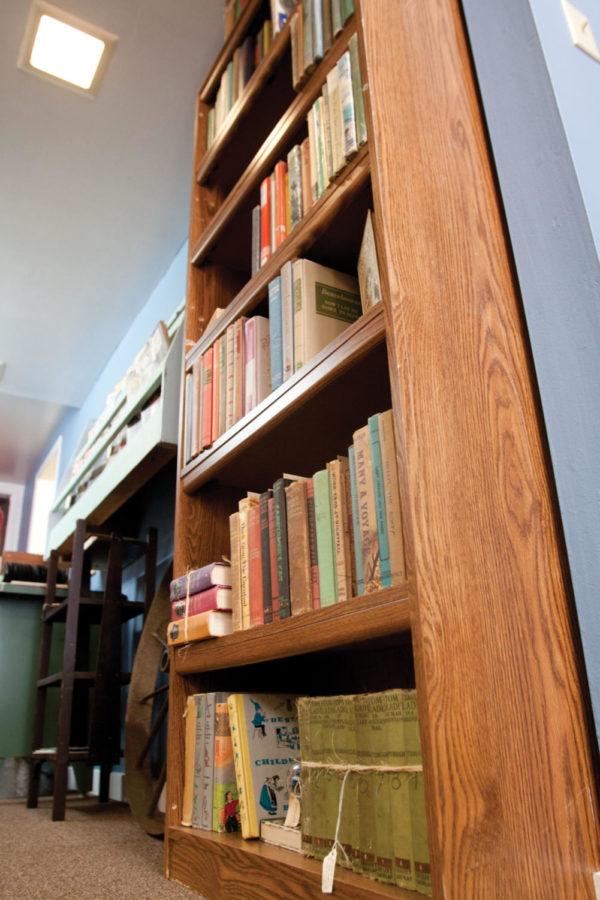

Anything But New opened Thursday, Sept. 1. It sells antique books in good condition.

July 30, 2012

Contrary to the implications of such magazines as Cosmo, Glamour and Vogue, women do not need to possess the idyllic physical features of fashion models to attain high levels of beauty. Personality, perception, a charming smile with honest eyes — in other words, what they do with their assets — are more than enough to make a woman the most enchanting of beings.

Used books and the stores that sell them are much the same way. There are years on them, but that doesn’t mean they’re all used up.

Copies of books that are reasonably worn out have a great deal of character their pristine counterparts in new bookstores lack. The pages are dog-eared, folder, stained; the corners are dull; the jackets might be torn; the spines have creases in them and the binding might be frayed.

In spite of (maybe even because of) their flaws, used books are to many people more alluring than new ones. Granted, new things are very nice. They are neat, nobody else has owned them, and their appearance is immaculate. They look exactly the way their designers and publishers envisioned.

Bought new, books are the Platonic ideal of their edition. Often, that makes them more desirable than a run-of-the-mill used copy that has seen better days and whose owner was careless and failed to treat the physical book as a vehicle for the ideas embodied by its words.

Indeed, there are two parts to a book: There are the words, which the author or publisher owns under copyright law, and there is the paper bound between two pieces of cardboard or a slightly heavier paper the rest of us can claim ownership to. The character of the words component to a book’s identity can be enhanced and even defined by the appearance and condition of the book itself.

Old and new alike, books make popular gifts. People love giving them; people love receiving them; people love endorsing them with their own dedications and benedictions. It is such personalization that has always caught my attention. I can hardly bring myself to write in books, even when making gifts of them. Now I’ve been through college it is easier to annotate margins and underline passages extensively — only in pencil, of course — but I have noticed it is easier to mark up a book that has already been owned by someone else.

Those markings, however, in addition to the hand that have held them and the stories of the places they have been, are just as much a book’s story as are the words that describe its characters. An author can try to convey one meaning, and each of his or her readers can have a completely different interpretation.

Jack Kerouac’s “On the Road,” for instance, is not significant to me because of the story his words tell within those pages. “On the Road” — my copy of “On the Road” — is meaningful to me because of the words written on its title page by the girl who gave it to me: “Mickey,” she wrote, “This has been to Europe, has been read in a monastery and in an airport and on a plane, and I hope it affects you like it did me in the midst of all those new and exciting places.”

Meaning is not always derived from the objective things everyone can agree on, the traits everyone can recognize as present or lacking. It does not depend on characteristics that are superficial and capable of identification by everyone. Often, validation or significance exists in a subjective story only the person — or, in this case, that book — has experienced.

The real indication of a book’s quality — how well its words were formed, conveyed and interpreted — lies in what people have done with and to it. That includes the notes they’ve written or scrawled in its margins and title page, and it means that some of the most used of books will always tell a new story.