Retrospective: Tom Hill, Munich and the ’72 Olympic Games

Photo courtesy of the Office of the Vice President of Student Affairs

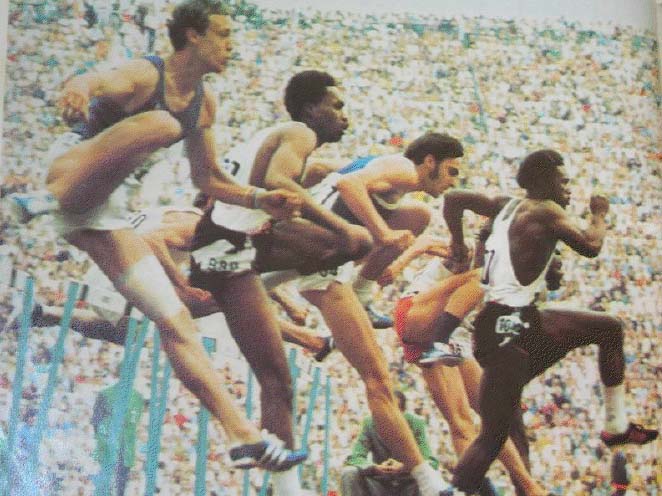

Tom Hill competes at the 1972 Olympics in the 110-meter hurdles.

July 26, 2012

It was like something out of a book, where you could see him go back and mentally relive each step of the race. Each hurdle. Each fan cheering for the red, white and blue.

Tom Hill, vice president of Student Affairs, relived a memory that day. A day where Hill was selected to represent the United States in the ‘72 Summer Olympics in Munich.

A smile took him back to the final race where he said he could remember every emotion in his body.

“The nerves began to take over,” Hill said. “But it didn’t happen until the final race. And you talk about drama: It’s a huge production.”

As he made the crowd-cheering noises with his voice, he smiled and laughed as if he were right back on the track .

“And as they introduced me, I don’t know how this happened, but there was a woman in the stands from Jonesboro, Ark,” he said. “That’s where I went to college.”

Hill said he remembers her calling out his name as he was being introduced by the announcers and couldn’t believe there were people traveling around the world to see him run.

It broke the concentration Hill said he needed to have. He started thinking about the fans and crowd.

And then a shot.

“We got started, and I was so nervous,” Hill said. “I was so nervous, that everybody got out of the blocks before me. If you can see somebody’s back, they’re clearly ahead of you.”

That’s when Hill said he was worried. He thought to himself he had come all the way to Germany to get last.

But in a 110-meter hurdle race, the race doesn’t end in 10-meters — luckily for Hill.

“So by the last hurdle, you don’t dare look over, [or] you’ll break your stride,” Hill said. “I managed to keep my head straight, and run like the dickens.

“When I got to the finish-line, … I turned my head as I leaned to my left.”

Here is where teammate Willie Davenport and Hill locked eyes as they crossed the finish-line. Rob Milburn and Guy Drut had already taken the gold and silver medals, respectively.

After getting across the line, Hill said he and Davenport went back and forth saying the other claimed the bronze medal.

“Then they started with the results and put Rob Milburn, first. Guy Drut, second. And then they stopped,” Hill said. “And there was this long pause which felt like 10 hours.”

“Then they flashed Hill, third. And I jumped about 10 feet in the air.”

The excitement flooded over Hill like he was experiencing it all over again.

But there’s a darker, more external side to this story. One that haunts some when the Summer Olympics roll around every four years.

Just outside of the arena where Hill was competing, foreign policy was undergoing change, and the world was witnessing a crime many hadn’t seen before.

Charles Dobbs, ISU professor of history, said a lot has changed since the Munich Massacre during the ‘72 Olympics.

“Security costs have gone over the top,” Dobbs said. “The private security firm [at] the Olympics failed to hire enough security personnel, and the British government provided thousands of British troops to augment security.”

Dobbs said the hype of security takes away from the event and from the athletes that spend so long training for the Olympics.

Also being in the height of the Cold War, Dobbs said the Munich Massacre was only a slight influence in change in foreign policy.

“The Cold War made foreign policy somewhat simple,” Dobbs said. “There were good guys and bad guys and few in between. One only had to decide who were the good guys and who were the bad guys.”

The Olympics have always been a time where countries showcase their best athletes, come together with other countries around the world and put aside governmental differences for 16 days every two years. Much has changed, but the core of the Games remains the same.