Editorial: Students can afford interest rate hike

Photo: Megan Wolff/Iowa State Daily

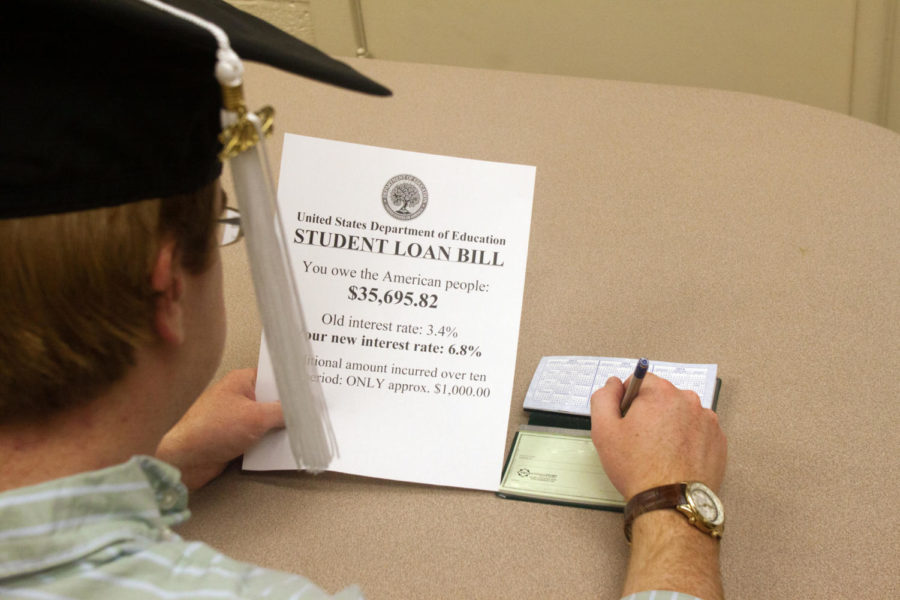

The interest rates on student loans are set to double in the near future, but the Editorial Board believes students will be able to handle the increase, as it only amounts to $1,000 spread over the course of 10 years.

June 27, 2012

Unfortunately, education is an interest group that, like every other interest group, protests wildly when its share of the public dole gets cut. Students are a part of that.

Whenever their interests as students are threatened with budget cuts, crowds of them can be relied upon to turn out and protest the changes. That truism applies across the world. Recently in the United Kingdom, students demonstrated against capping tuition at £9,000 rather than the £3,290 limit then in effect. Here in Iowa, Regents Day 2011 at the State Capitol came under fire as a partisan event that protested cuts to education Republicans wanted to make that year.

The cut now looming above students (or so we are told) is the possibility of allowing the interest rate on Federal Stafford student loans to double July 1 from 3.4 percent to 6.8 percent. Both Republicans and Democrats in Congress agree that the interest rate should be kept low; the real question — and the political grandstanding that has surrounded this issue since the new year — is how to fund the lower interest rate.

Right now, fixing the interest rate on Stafford loans costs the federal government about $6 billion. By contrast, estimates say doubling the interest rate would cost students, individually, about $1,000 over the 10-year period in which they repay their loans.

Whoop-de-do.

The United States overspent itself by $459 billion in 2007-08; $1,413 billion in 2008-09; $1,293 billion in 2009-10; $1,300 billion in 2010-11; and this year, the national deficit is expected to add $1,327 billion to the national debt. $6 billion in that is truly a drop in the bucket, but it is either $6 billion that can be allocated to other programs or left unadded to the debt, with which we saddle future generations of Americans.

Going to college is, for many young people, a way of stringing out their youth as they drag their degree out through five or six years, or as they go to graduate or professional school in the hopes that, by the time they graduate from that program, the economy and their job prospects will have improved. At some point, though, we have to take responsibility for bearing the cost of our own education, and $1,000 is not much when spread over a decade.

At some point, we all have to leave Neverland and grow up.

The attention that the interest rate hike has received over the past several months has become a much wider debate about how government spending should be funded. The question before us, so it would seem, is whether we should fund some programs by cutting others and so prioritize the subjects of public money, or whether we ought to fund everything that should be funded, and do so through tax increases.

That framing is overly simplified.

With this, as with many other issues, the words of President John F. Kennedy ring true: “Ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country.” As holders of four-year degrees, graduating students are among the most competitive prospective employees. They can take care of themselves. They can afford paying an extra $1,000 over 10 years.

Similarly, members of Congress should, both as their deadline of July 1 draws nigh and in the future as they have opportunities to affect education policy, make decisions that are right for the whole United States, not just a voter demographic.

We cannot have our cake and eat it too.