Swine study follows path of salmonella from animal to human

March 28, 2012

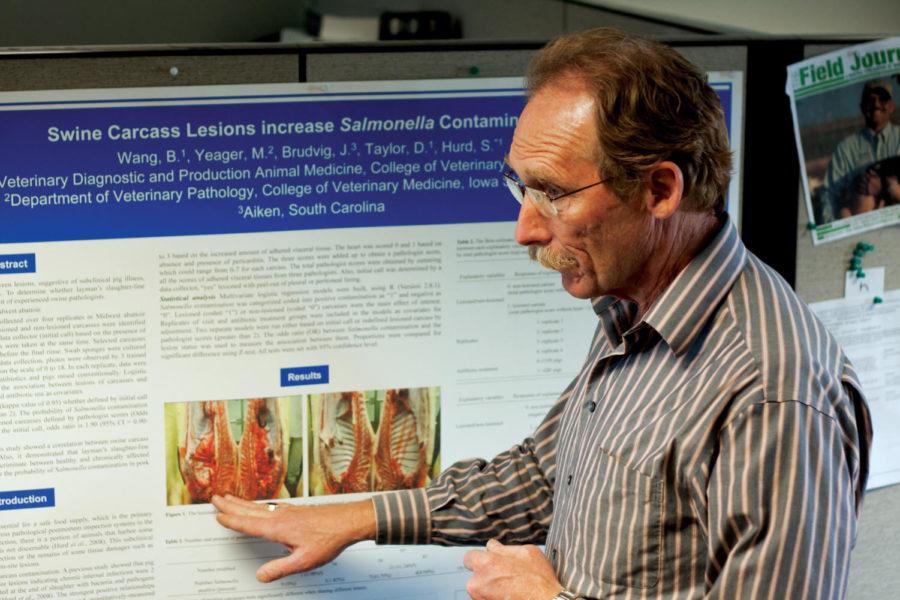

Faculty from Iowa State’s College of Veterinary Medicine and Michigan State University did a study on the link between lesions in pig carcasses and contamination of the same carcasses with salmonella.

“We were trying to see if there was any link between animal health and human health,” said Dr. H. Scott Hurd, associate professor and director of graduate education at the College of Veterinary Medicine.

Hurd has been working with salmonella for the past 20 years, originally just working to keep it off the farm.

“Then I got into the debate about whether or not there should be antibiotic use in livestock. Lots of people think antibiotics in livestock affect human health, but if we don’t use antibiotics, the pigs will, and cause more people, to get sick,” he said.

Lots of people, Hurd explained, do not really care about the health of the animal, but do care about the public health.

“Our theory is that as animal health concerns get smaller, there will be more pigs that won’t visibly look ill but will have these lesions, which will lead to more inspection,” Hurd said. “This will lead to more contamination and will make more people sick.”

The study used 358 pig carcasses. More than 150 of the pigs were raised without antibiotics and 202 pigs were raised conventionally and with antibiotics.

The pigs were otherwise raised the same, with the same veterinary care, housing environment and feed.

The results of the study found that carcasses with lesions were 90 percent more likely to have salmonella contamination.

Out of the 156 pigs being raised without antibiotics, 27 of them were contaminated with salmonella, while out of the 202 pigs raised with antibiotics, only nine were contaminated with salmonella.

This, Hurd explained, is because a pig that visibly looks well, but has adhesions inside the carcass, are going to be handled more.

“Part of our theory was that when a person is cutting open pig carcasses that are visibly healthy, they might find an adhesion, which they jerk out and move on to the next one. This contaminates their hands, though, and they don’t stop to wash them, so they end up contaminating other pigs as well,” he said.

These pigs are called peelouts because the pleural lining inside is “peeled out” so that the pigs look normal.

Hurd said that this research is fairly new. Only one other study in birds has been done, and they used this as a model.

The study did show that the health of the animals — in this case, pigs — does indeed affect the health of the public.

“Lots of people think antibiotic use in livestock will affect human health. If we stop using antibiotics in pigs, though, there will be more pigs that are visibly healthy but may have lesions or adhesions, which will cause more handling and more contamination,” Hurd said.

Another reason people do not like the use of antibiotics in livestock was explained by James Tiedje, MSU University distinguished professor of microbiology and molecular genetics and of crop and soil sciences.

“The growth of antibiotic resistance in pathogens is a huge challenge for society around the world. Studies to understand what contributes to the spread and what interventions can help control the problem are vital,” Tiedje said.

Hurd, who did not know what causes the lesions and adhesions in the carcasses exactly, wished to pursue further research in this area.

“We just received funding to do a study on what causes the lesions in these pigs. We know it’s some past health problem, but we’re not exactly sure what it is,” Hurd said.

He also said he wants to look at the human health aspect of it.

“I want to be able to figure out how much more food borne illness it will cause,” he said.