Iowa State lab joins search for HIV vaccine

February 20, 2012

Iowa State’s College of Veterinary Medicine has joined the pursuit of finding a vaccine or cure for AIDS, a deadly disease that has been an issue for more than 30 years.

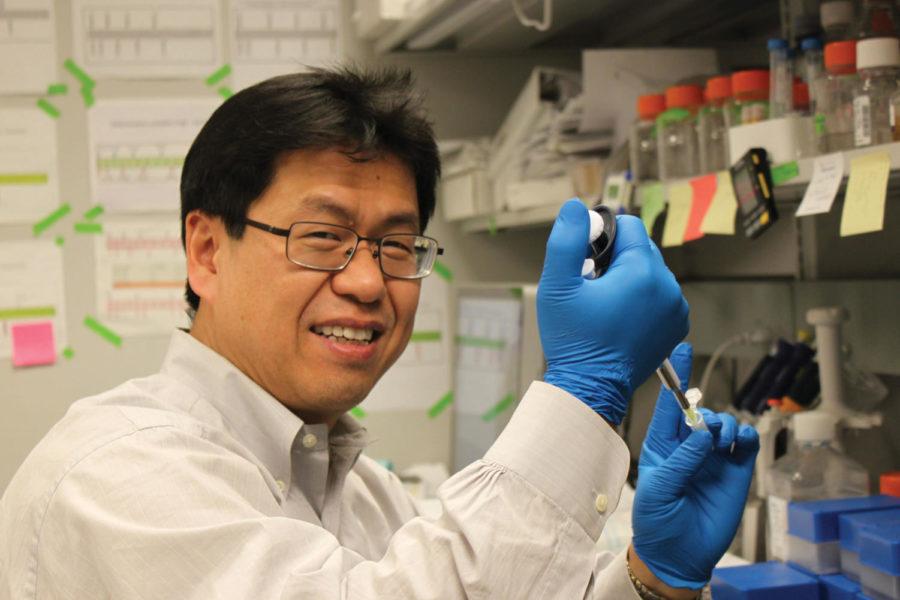

About two years ago, Michael Cho came to Iowa State from Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio, and brought with him his lab. Cho has been working on a vaccine for HIV-1, the virus that causes AIDS, for more than 10 years.

“HIV-1 attacks CD4+ helper T cells and kills them,” Cho said.

The CD4+ helper T cells, he explained, are the cells in the immune system that look for discrepancies, such as bacteria or a virus, and signal to the rest of the immune system that they’re there.

“The proteins we have been focusing on in the virus are gp120 and gp41 glycoproteins. The gp120 protein binds to the CD4+ helper T cells because CD4 is a specific receptor for it,” Cho said. “After it binds, the gp41 protein fuses the two together so the virus can enter the cell and integrate its nucleic acid information with the cells.”

After the human cell is infected, the virus can either stay dormant or create more of the virus, which will then be sent out to infect more cells. This is why Cho’s lab is trying to focus the gp120 and gp41 proteins that allow the virus to enter helper T cells.

“We are working on a subunit vaccine that is protein-based,” said Saikat Banerjee, graduate student in biomedical sciences who works in Cho’s lab.

There are many people working on this project with Cho’s lab from all around the country, including people from Albert Einstein University in New York and Case Western in Ohio, as well as the people who work in his lab here at Iowa State.

“We make these proteins by cloning them,” said Habtom Habte, who also works in the lab. “We then immunize rabbits with them to see how their immune system responds.”

“The problem with HIV is there are so many antigenic variants, which are generated as a result of high mutation rate,” Cho said.

Another problem is that the virus infects and incorporates its genome into the cell.

“We must inhibit the virus from getting into the cell. Once the virus is in the cell, it is very hard to neutralize,” Habte explained.

Despite these problems, the results the lab is getting seem hopeful.

“There is one very strong candidate that we’ve been seeing make antibodies, so we’ve been working a lot with that one,” Banerjee said.

Cho and those working in the lab continue to look toward the future.

“Our future goal is to improve this vaccine so that it can be more effective,” Cho said.