Perdios: A historical, cultural rift in Campustown

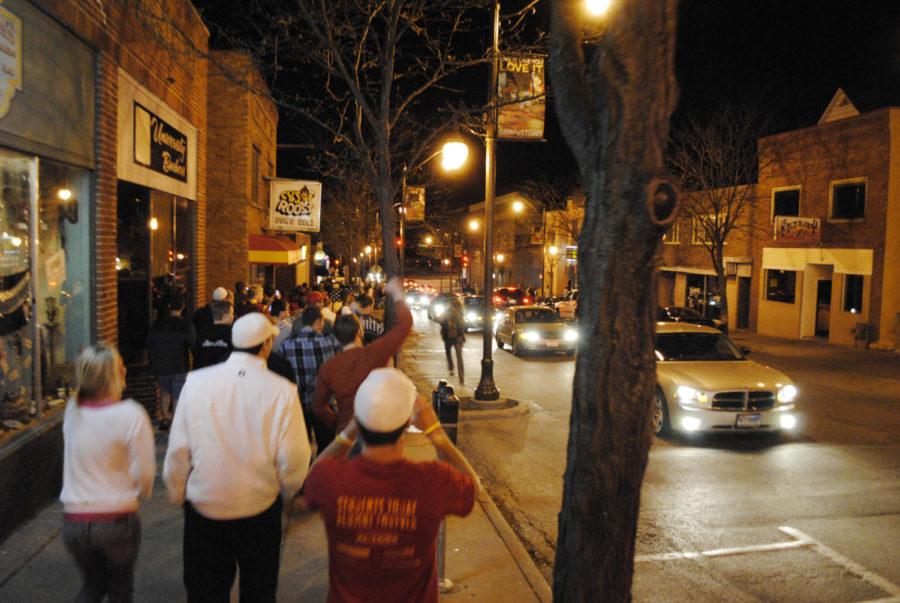

Photo: Jake Lovett/Iowa State Daily

Community members celebrate the announcement of the death of Osama bin Laden on Welch Avenue on Sunday night.

February 3, 2012

The discussion over Campustown’s fate continues. I have experienced Campustown as an undergraduate and now as a graduate student and an Ames resident. Over the years, I’ve watched Campustown be a source of controversy in the Ames community. I believe it will remain this way regardless of whatever “revitalization” or “facelift” Campustown receives to bring in demographics from outside the student body.

What began as unincorporated land south of campus in 1858 now exemplifies the cultural rift between long time Ames residents and Iowa State students. This rift will hinder compromise between all parties involved in Campustown’s development. Once you understand the history of Campustown, it’s not hard to see why.

If you think Campustown is “tired looking,” “run down” or “blighted” today, just imagine what it was like in 1900. Campustown was basically a colony of Ames. Residents called the place “Dogtown” because of its lack of clean water, sewer systems and electricity, and because of the occasional outbreak of typhoid. Students lived in wood-framed houses called “prairie dogs,” which could burn quickly. Ames had annexed West Ames back in 1893 to receive state funding and tax benefits. But in 1916, residents tried to secede because Ames took so long to modernize the area. The attempt failed. In 1922 during the first Veishea, students renamed Dogtown to “Campustown.” Perhaps this signifies that the cultural rift can be mended somewhat.

The next phase of Campustown’s history is even more important to the current discussion, since it resides within the collective memory of longtime Ames residents. Somebody who graduated from Iowa State in the late 1950s and remained in Ames would have watched Campustown transform into something almost unfamiliar. Even those alumni from the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s would see changes that they might not like.

In the decades following World War II, Ames faced a large influx of students. When William Parks became ISU president in 1965, enrollment stood at 14,014 students. When he retired in 1986, enrollment had soared to 26,529. During this time, the number of bars and student residences increased there. By the ’90s, high-rise apartment buildings had started to grow from the bulldozed remains of the prairie dogs.

The population of Ames also shifted farther away from campus during this time. Commercial districts developed elsewhere to accommodate this shift, such as North Grand Mall and South Duff. The university also lifted the ban on freshmen and sophomores from having cars. Students became more mobile and could shop elsewhere. Thus, the number and different kinds of retail stores in Campustown declined.

Most importantly, by the ’80s, Campustown and Veishea had become connected with the tradition of mass alcohol consumption and rioting. Certain longtime residents may recall how “Ash-bash” in 1985 got out of control. Police closed down greek community celebrations, and people took to the streets. Veishea floats burned. In 1988, bonfires erupted along Welch Avenue as 5,100 people rioted for two consecutive nights. In 1992, 8,000 students and attendees converged on Campustown. Riot police greeted them. In 1999, a crowd estimated anywhere between 300-1,500 students marched out of Campustown, converged on the Knoll, and demanded an end to dry Veishea in not-so-polite terms. Veishea 2004 saw 2,000 students confront police and ended with the iconic image of a burning dumpster. Although in subsequent years (except for a disturbance in 2009), Veishea has remained relatively quiet. Certain policies set by the university and the city of Ames seem to have worked.

Some proponents of Campustown’s revitalization have argued that the current state of Campustown hurts enrollment, or somehow detracts from the local economy. But has anybody put forth concrete evidence of this in the form of enrollment numbers and lost dollars? No, we deal simply with aesthetics, altered by the nostalgia and history of days long ago and smeared with the anxiety of having another riot.

For me, Campustown has some nostalgia. But you know what? There comes a time when you have to realize that those undergraduate days are over, when you need to grow up, move on and let another generation enjoy Campustown. I go there occasionally to eat lunch (the Fighting Burrito will always be the “Flying Burrito” to me). But the nightlife, the job opportunities, the retail stores and the living arrangements are not really geared toward Ames residents 25 and older.

The cultural rift is there and will not close anytime soon. Even if you don’t believe this, some serious questions need to be asked before more money is spent on Campustown’s revitalization. For longtime Ames residents the question is: Would you want to live, shop, work or play in Campustown, even after changes are made? For Iowa State students: Do you really want longtime Ames residents to live, shop, work or play in Campustown?