Snell: December means more than a holiday break

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

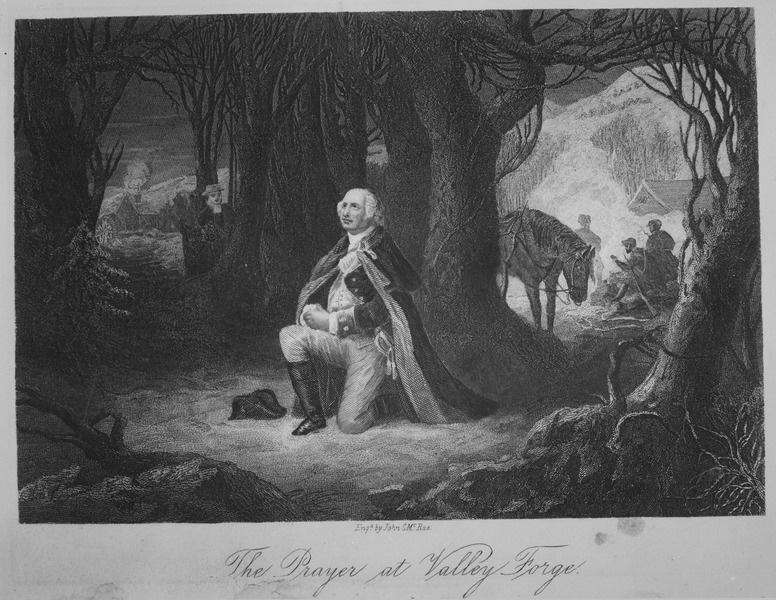

The Prayer at Valley Forge

December 14, 2011

For some of you, this Friday will be

your last day as a college student. I congratulate you and wish you

well. But I do so with a touch of sadness, for as a returning

student I know better than most just how special this time is.

You may be desperate to be done now,

but with age comes wisdom, and wisdom will eventually reveal just

how wonderful the last few years have been for you. I wish for you

that this day comes sooner than it did for me.

For all of us though, whether only

for a few weeks or forever, we face the holiday break. In the best

spirit of America, the meanings and traditions of the holidays are

as individual and unique for us as we are ourselves.

A lot has happened in the month of

December through the years. I am a history major who comes from a

family with a military tradition, and have myself participated in

our current and ongoing war. These and other things combine to

color my outlook on the month of December and generate within me my

own personal meaning for the holidays.

We associate the year 1776 with

independence, patriotism and freedom from tyrannical rule. The

truth of 1776 is much different, however, as the American

experiment was very much in danger of being extinguished before it

got started. Gen. George Washington was handed defeat after defeat

by the British and he very nearly resigned.

In a letter to his cousin Lund in

December 1776, Washington said, “I wish to Heaven it was in my

power to give you a more favourable Acct of our situation than it

is-our numbers, quite inadequate to the task of opposing [the

British Army] … We were obliged to retire before the Enemy, who

were perfectly well informed of our Situation till we came to this

place, where I have no Idea of being able to make a stand …”

We were desperate and the fate of the

newborn nation was hanging in the balance. But shortly after in an

act of brilliance and desperation, Washington crossed the Deleware

River, on Christmas Eve, and soundly defeated the Hessians in the

Battle of Trenton.

One year later, in December 1777,

Washington had cause to wish he was back in New Jersey. The

Continental Army found itself at a place called Valley Forge in

Pennsylvania. Starving and afflicted with dysentery and other

diseases, we endured the greatest hardships yet.

Many of our men had no clothes for

winter, and several were without shoes. Your revolutionary

ancestors stood barefoot on their hats in the snow and drilled with

their muskets.

On the brink of obliteration,

Washington was despondent: “… three or four days bad weather

would prove our destruction. What then is to become of the Army

this Winter? [A]nd if we are as often without Provisions now, as

with them, what is to become of us in the Spring …?”

Washington continued: “although

[Congress] seems to have little feeling for the naked and

distressed Soldier, I feel superabundantly for them, and from my

soul pity those miseries, which it is neither in my power to

relieve or prevent … [I]t adds not a little to my other

difficulties and distress, to find that much more is expected of

me, than is possible to be performed …”

Yet we rallied and won the Battle of

Monmouth a few months later, and the tone of the Revolution

changed. The Continental Army came out of Valley Forge something

transcending their true state and Washington could barely do

wrong.

To put it bluntly, you have your

freedom today because starving, nearly naked men who couldn’t keep

their lunch down wouldn’t give up.

December 1941 brought another test of

fortitude when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor and surrounding

targets, causing 3,741 military and civilian casualties. We were

caught unprepared and were fairly beaten, but as always, we joined

together and eventually accomplished the monumental.

A few years later, in a scene

reminiscent of Valley Forge, the Germans had the 101st Airborne

surrounded in the Battle of the Bulge in December of 1944. Belgium

had record low temperatures and snowfall that year, as if God

himself wanted us to lose. Our men marched in with little ammo, no

winter clothing and not a hope in hell. We were socked in and

screwed over, but we came out on top like we always seem to.

So as you go home this break, pause

during the holidays and think about those paratroopers who sat in

foxholes, literally freezing and starving, while enduring constant,

incessant German artillery and armor attacks. Think about the young

men in Pennsylvania so long ago who shivered barefoot, standing in

the snow bank on their hats, drilling with their muskets while

trying to learn to be an army.

Give some thought and silent thanks

to those Americans out there who have lived and currently are

living the very ideals that make the endurance of this country

possible. Sacrifice isn’t just a catchphrase, and patriotism isn’t

just waving a flag. They really and truly mean something.

Merry Christmas, everyone.