Iowa State receives criticism for involvement in potential land grabbing

Iowa State has landed in some hot water regarding its involvement with an international land development project in Tanzania.

December 6, 2011

Several advocacy groups and media organizations including Dan Rather Reports and the Oakland Institute have released reports condemning an international land development project involving Iowa State University. The Oakland Institute, a human advocacy organization, released a report critical of Iowa State’s role in the project.

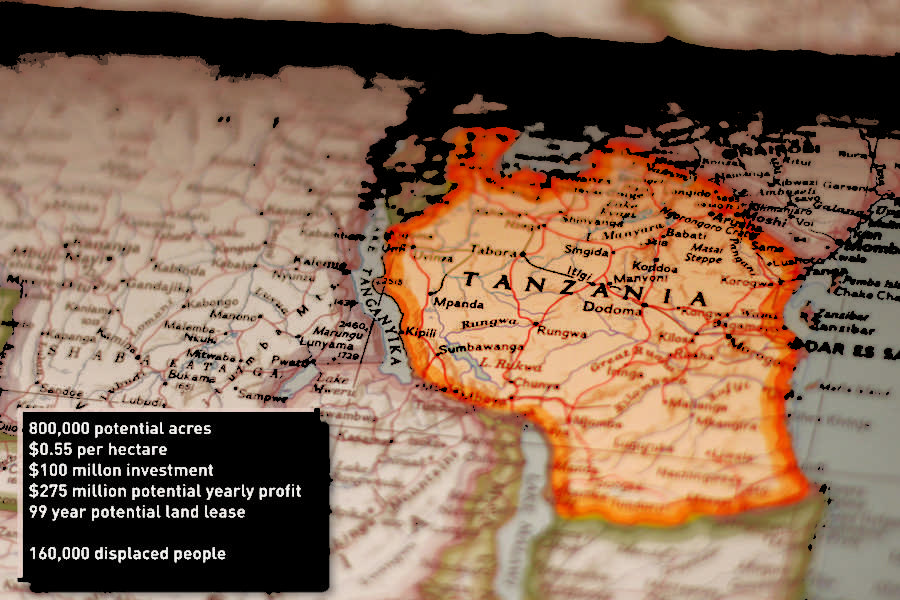

Several Iowa-based companies are working on a controversial land investment deal in the Sub-Sahara African country of Tanzania. AgriSol Energy LLC and Summit Group are attempting to work out a deal with the Tanzanian government that would allow them to lease land in the western part of the country for agricultural development.

Iowa State conducted research in early 2011 to offer advice to help the potential for success in the program. However, the project has continually been referred to as a “land grab,” or a scheme that aims to take land out from under Tanzanian people and leave it to large companies for the taking.

The investment companies claim that they aim to develop the fertile land in the rural areas of the western region of the country. There has been strong criticism from NGOs and media outlets due to the accusation that refugees or peasant farmers are currently occupying the land AgriSol hopes to acquire.

AgriSol Energy Tanzania Limited, a joint venture between AgriSol Energy LLC and Serengeti Advisers Limited, claims that the land investment is for the benefit of the local economy and aims to make Tanzania an agricultural powerhouse.

“Our objective is to create a large-scale agriculture zone dedicated to producing staple crops and livestock that will help stabilize local food supplies, create jobs and economic opportunity for local populations, spur investment in local infrastructure improvements and develop new, transparent markets for agricultural products,” said the AgriSol the website.

It also claims that profits gained from the farms will provide for co-op organizations and community investment.

However, Anuradha Mittal, executive director of the Oakland Institute, vehemently believes that the investors’ intentions are not within the best interests of Tanzanians.

“If you look at the business plan, even if they just planted with corn, at the prices of corn this year, they would be making a net profit of over $300 million a year,” she said. “And that they have all kind of strategic investor status that they are demanding, that means they don’t have to pay import duties, they don’t have to pay property taxes, they can repatriate their profits. So basically you leave nothing in the country.”

Mittal is not alone in her skepticism of the project. Several experts in the field of agricultural development are also not confident in its success.

“For one thing, there’s no question that this is a land grab,” said Dennis Keeney of the Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy and former head of the Leopold Center. “They’re getting huge tracts of land that will not be beneficial to the Tanzanian people.”

He was wary of the effect farming will have on the land as well, especially given the fact that row crops like corn and soybeans are extremely hard on soil.

“Odds are they’re going to have a hard time supporting an irrigated crop like corn or soybeans,” he said. “The secondary effects are always different than what you think they might be.

ISU Professor Emeritus Neil Harl, who is an expert in agriculture law and has worked extensively in agricultural development projects, was also willing to weigh in on the issue. One of his primary criticisms is that there is a lack of transparency within the business plan, and it is difficult to tell what the role of the companies will be.

“If [AgriSol] would please give a little more insight into the objective of the project, we would be more at ease, particularly in light of the involvement of an educational institution,” Harl said.

Harl said one of the most important questions as to whether it is designed for long term. First, it is not clear what design is and second, whether it aims to maximize returns for interests or to help Tanzanians.

He said that the crops are typically for export, and that capital is rarely funneled back. Another criticism of his is that there is very little infrastructure in the country, especially with regards to irrigation, roads and railroads — all of which would have to be built by tax money, levying an even heavier burden on the Tanzanian people.

“This is a bit worrisome to these people. How is this project going to benefit them, if it does?” he said. “It isn’t creating a model of typical displaced person can use.”

AgriSol countered the argument, claiming that they would work directly with the farmers according to their website: “Yes, small farmers will be consulted during the next phase of our project’s development. We have just completed our feasibility analysis and preliminary planning, which included a series of listening sessions and a workshop led by us, to solicit local input from political, university and technical leaders at the national, regional and district levels. Twelve key needs were identified by our fellow Tanzanians at that workshop and will be incorporated into our program.”

Accordingly, Mittal is critical of Iowa State’s role in the project.

“This is an investment where investors are going in with a state university very actively involved in it with this investor, and they’ll be to displacing people who have been living there for 40 years,” she said. “There are a few things that stand out. One is the business plan. They’re paying almost nothing, it’s like 50 cents or whatever for the land.”

In its report on the project, the Oakland Institute claims that as many as 160,000 people are going to be relocated on by of the project.

“People are not happy about being moved. They are being told they will have $200 when they move, and that’s when they’ll become a citizen,” Mittal said. “Their citizenship is based on them agreeing to moving away and dismantling their own homes. So there’s no relocation plan other than something that sounds very harsh.”

Keeney, too, was worried about the fate of the potentially displaced people.

“They’re just going to have to go wherever they’re told. It’s not going to be a good outcome,” Keeney said. “It just seems to be the way people treat those they have power over.”

David Acker, associate dean of global agricultural programs at Iowa State, sees things much differently. He was the prime contributor in Iowa State’s role on the project and begins by stating that the term “feasibility study” is inaccurate, because Iowa State played a different role in the project.

“I think ‘feasibility study’ is not the correct word. I would describe it as ‘pre-planning activities.'”

His previous work in Tanzania led him to want to work alongside the Tanzanian people and therefore to spend time in the country doing research. Acker conducted listening sessions with the Tanzanians and developed a list of 12 areas with the Tanzanians that they thought an agribusiness should have in order to be socially responsible.

The list included programs like community trust funds and AIDS education, which he presented to AgriSol. When it came to actual land studies, however, they had hired consultants outside of Iowa State, Acker said.

“That interested me because it’s a new model,” he said. “My own heart of hearts, what I wanted to do was to figure out a way to bring some investment to Tanzania that would help Tanzanians. OK, it’s going to make some money for investors, otherwise hey, that’s why they call them investors. They don’t want to go and give money away. They’re looking for a way to make money, but they want to file money back in.”

However, Acker is critical of Oakland report because he claims that the areas containing refugees were are not being considered by AgriSol.

“If these plots were ever under consideration, they are not now,” he said. “That’s an awful thing to even consider. If you did find a set of business people who were willing to have anything to do with kicking refugees off the land, who would want to have anything to do with them? Not me personally, not Iowa State.”

The acquisition of the land is also controversial due to Tanzanian laws on land ownership. Currently, Tanzanian law prohibits ownership of land within its borders by anyone who is not a Tanzanian citizen. AgriSol plans to avoid the issue by leasing the land from the government instead of purchasing it.

The final piece of the puzzle is the conflict of interest presented by Bruce Rastetter’s role in the projects and his position as president pro tempore of the Iowa Board of Regents.

“At first I was very concerned because they were stepping in a role they couldn’t win,” Keeney said. He claimed that Iowa State’s decision to step back from the project was a result of the potential fallout of the conflict of interest being exposed to the public.

“They were worried about the curtain coming up on this one and it not looking good,” he said. “Whether or not ISU would have done it, whether he was involved or not is another questions; we may never know the answer.”

However, he was not completely against the project. He also claimed that it could potentially help the Tanzanians. Ultimately, though, he feels that even with the decreased role of Iowa State, the project is still a bad idea.

Rastetter would not speak with the Daily regarding the project, but in a disclosure statement issued by Rastetter on this past May, he admitted that there was a conflict of interest.

“I am a shareholder in Agrisol Holdings, which is working with the College of Agriculture [and Life Sciences] at Iowa Sate University on a Tanzania Ag Project. Previous to becoming a regent, Agrisol provided a scholarship commitment and travel expense reimbursement for travel to TZ. I additionally have three gifts to Iowa State University and the University of Iowa.”

Given the conflict of interest, Iowa State chose to step away from direct involvement in the project, only offering to provide basic advisory information in the future.

“Iowa State had to look at its role and say, ‘As much as we’d like to be involved with this, it would be a conflict of interest, or at least perceived as a conflict of interest if we were working on an investment that one of the regents was involved with,'” Acker said.

However, Iowa State will still be able to provide information on past projects to help advise investors, just as it would with other NGOs and other companies.

“We can’t be involved anymore and that’s a key point. What can we do to be helpful that doesn’t involve a direct involvement?” he said. “We would basically share any of the information we have on Uganda and our approach there, hand over the blueprints; it’s public information.”

However, he is still confident in the project.

“Even if we think it’s a good project, there’s no way we could be involved directly in it,” Acker said. “I have my personal regrets because I feel like we could have done something good, but I think we did the right thing by stepping back.”

Acker also wanted to counter the argument that there were currently no plans, on behalf of Iowa State or AgriSol to be involved in other areas. Acker said AgriSol was given list of 30 parcels of land in Tanzania, places with refugees was on list, but they discarded them like other places because they had found the the Tanzanian government had not given then adequate information after doing their own investigation.

“That’s probably the sorest point because that became the focus of Dan Rather. It’s quite a black eye for the AgriSol people,” he said. “They’re investors, and they want to make money; there’s no question about that. But to be considered to be kicking poor people off the land — you can dislike an investor, but I think they felt that that was kind of a cheap shot.”

Acker said that he and the university would be very happy to work with any party as long as they have a commitment to sustainable rural livelihoods, but certainly would not be anyone who would kick people off of land.

“All I can say is from Iowa State’s point of view is that we have never considered working in those areas, and would never consider it,” he said. “Our commitment was to sustainable rural livelihoods of vulnerable farmers, vulnerable farm families. I didn’t see our role being involved in the profit aspect of it.”