Hanton: Guantanamo is epitome of post-9/11 fear

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

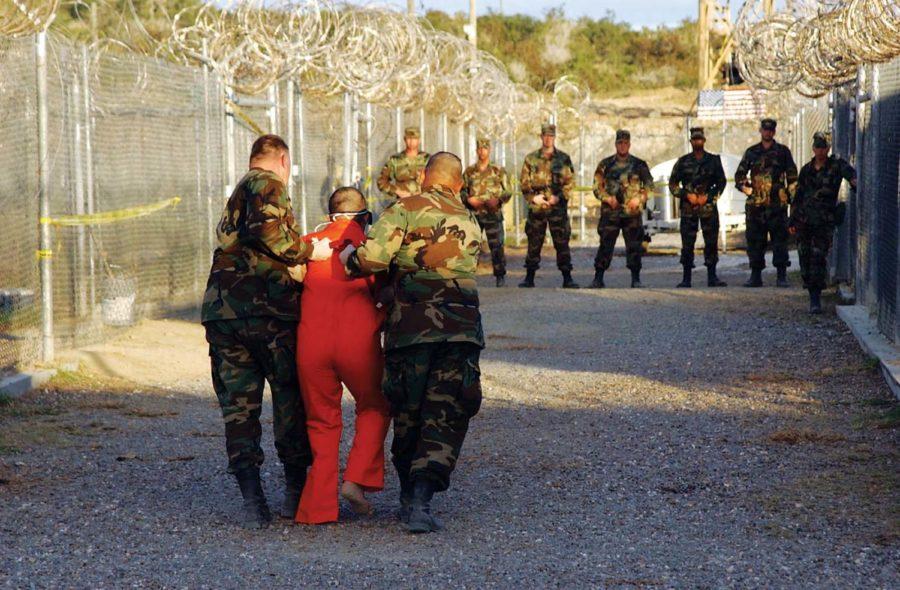

Two US Army Military Police escort a detainee, dressed in an orange jumpsuit, to a cell at Camp X-Ray, Guantanamo Bay Navy Base, Cuba. Camp X-Ray is the holding facility for detainees held at the US Navy Base during Operation Enduring Freedom. Photo by Mate 1st Class Shane T. McCoy

September 11, 2011

Following the events of Sept. 11, 2001, fear became the driver for the United States military’s actions. The nation and the military wondered, “Who are these foreign men who would kill themselves in an attempt to murder thousands of Americans?” “Are there more of them?” “How can we stop them?”

In an attempt to gather as much information as possible as quickly as possible, the Pentagon and the White House decided that any valuable individuals they captured in Afghanistan and other areas abroad would be labeled “illegal combatants” rather than “prisoners of war” — allowing the military to argue that the Geneva Convention protections for prisoners of war do not apply.

They quickly set up and began using a camp on the Guantanamo Bay Naval Base in southern Cuba to hold and interrogate prisoners captured abroad. The base was designed to specifically be outside of the jurisdiction of the United States court system, where the military could use an executive order from George W. Bush that prevented mainland courts from hearing Habeas Corpus writs (legal demands to be taken before a court) from prisoners and the base’s remote location to hold prisoners indefinitely.

If you take the time to read some of the 20,000-word part III of the Geneva Convention relative to the “Treatment of Prisoners of War,” you will quickly realize that a number of these “minimum requirements” for the treatment of prisoners, including restrictions on close confinement and transportation from a war zone for starters, have not been applied to prisoners at Guantanamo. And these are just the minimum requirements.

Have we, as a nation, stooped so low in our fear that we are not using humane requirements above those of the convention, but instead figuring out the best legal ways around this cornerstone of international law?

Former President Bush and Vice President Dick Cheney had no problem supporting the detention of illegal combatants at Guantanamo Bay without trial as a way of preventing terrorism, and it seems President Barack Obama is following suit today. After initial campaign calls for the immediate closing of Guantanamo, Obama made strides toward removing unnecessary inmates from the prison, but approximately 200 prisoners remain.

Obama’s attempts to move the remaining inmates to federal prisons on the mainland were foiled by Congress, which eventually passed legislation expressly barring him from using any funds to move the prisoners from the base in Cuba. That legislation was tied to a defense authorization bill, so like the debt-ceiling debate, Obama was forced (blackmailed, some might say) to sign the bill including the Guantanamo provisions or else the military would not be paid.

In my mind, while there are many choices the government could make to deal with Guantanamo, there is only one correct choice. That choice is to evaluate all detainees and set court (or military tribunal) dates for any inmates that have sufficient evidence against them. If there is not enough evidence, which is the case for many of the prisoners, then there is no choice but to release them. If we actually believe in the rule of law and the power of the courts — there is no other choice.

Of course, we can try to keep the “bad ones” on a leash and use all the resources at our disposal to keep them under surveillance to then later re-capture and prosecute them for anything we can prove. But until that time, we simply cannot hold them indefinitely without trial or due process and sleep soundly at night.

Just consider it for one minute. What would you feel like if, guilty or not, the U.S. government one day snatched you from your home and stuck you on an island in an 8-by-7-foot cell with as little as 2 hours of exercise time outside per day? Then they held you there with no hope, no hope of release and no hope of escape — perhaps because they think you’re a terrorist but don’t have enough evidence to prosecute you for your crimes — so you live in limbo.

This is not just a fictional idea. I found interesting accounts about Majid Khan, a legal U.S. resident who has been held at Guantanamo Bay since he left the U.S. to visit his wife in Pakistan back in 2003 due to his family ties to purported terrorists. He has been held in detention without trial for eight years now. Eight years! For college students like us, that seems like a lifetime — and perhaps it is.

Khan, now 31, has been held in prison by the CIA and U.S. military since he was 23. In the next eight years of my 23-year-old life, I’d like to get a good job, get an apartment or condo, spend quality time with friends, perhaps get married, maybe have kids — and this man, who is not so different from me, has had only the prospect of a small cell and little human contact for years.

Who are we? What did we do with the pre-terrorism United States of America that believed in the rule of law and the justice of the courts? Are we so afraid of these 200 men that we must create a level of hell here on Earth and leave them there with no way out until the end of the endless war on terror?

Some may have done bad things, made bad decisions based on skewed religious beliefs, but they’re not animals to be kept in cages at the zoo — too dangerous or changed by captivity to be released back into the wild. They’re humans like us, they’re men like us, and they should be treated as such.

So do me a favor and call or email your representatives and remind them of the facts of the matter. This is not what we do to our fellow man. We should be apologizing profusely to the 775 men who were held at the prison rather than writing new laws to imprison the remaining few forever. I hope Obama can follow through on his promise to close Guantanamo, as it has hurt our country’s image too much already.