Ames Lab uranium cause of cancer in workers; compensation claims approved

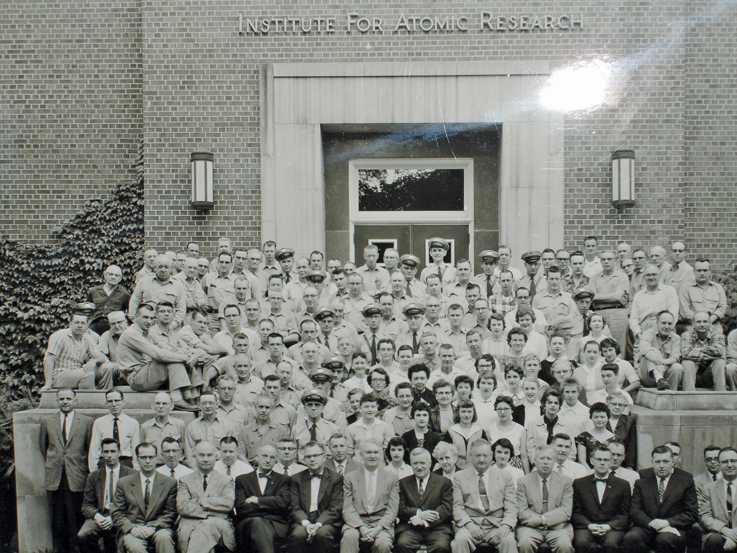

Courtesy photo: Laurence Fuortes

Ames and ISU researchers were among those exposed to radiation in the 1950s and 1960s during weapon development. Victims of this exposure are to receive financial compensation.

November 10, 2010

No one knew that the secret down the hallway was killing them.

The mysterious men with the coats would walk by the office with the big windows and the walls of filing cabinets every day but wouldn’t say anything to the three secretaries sitting at their desks.

Only a few feet away from the clicking noises made by the secretaries using their phones, the scientists who researched for the Manhattan Project from 1942 to 1946 were still doing top-secret research with radioactive materials including uranium.

The scientists, some of who were ISU faculty and graduate students — including chemistry professor and first director of the lab Frank Spedding — were still conducting this research at the Institute for Atomic Research, now the Department of Energy, at the Ames Laboratory, 10 years after they produced more than two million pounds of pure uranium for the atomic war effort.

A plaque commemorates the scientists’ achievements in the spot where a converted women’s gymnasium and sister location to the main laboratory called “Little Ankeny” once sat.

Now, all workers who worked at the Ames Laboratory from 1955 to 1960 who filed a claim that they have had 1 of 22 types of cancers after being employed at the lab will automatically be compensated for their misfortune.

Senator Tom Harkin pushed in October for the speedy compensation of the lab workers.

“[This] is welcome news for the workers and families who handled incredibly dangerous materials in the earliest days of the cold war and developed cancer as a result of their work at the Ames Lab,” Harkin said in a news release. “The federal government continues to expand the cohort impacted by this exposure, proving that we have, and will continue to owe, these workers a great debt for their contribution to our national security.”

Two-thirds of the affected families included in a Special Exposure Cohort filed claims that were exposed between 1949 to 1974 while working at the Ames Lab, according to the news release.

Although it is uncertain of how many former lab workers have been or will be diagnosed with cancer, a woman who worked in the lab said she believes there are hundreds of workers who have been affected and many who still have yet to even hear about their right to file a claim.

One of the three secretaries who would see the men walk by to begin work with the harmful chemicals every day in the three-story building is one of the two-thirds of families who have already filed claims with the Department of Labor.

She began working at the lab in 1957 when she was 18 years old.

Her parents were proud of her new job as a travel clerk where she checked in scientists that came from different states and maintained personnel files for lab employees.

One of those employees, Jean Kestel, was hired to observe screens and compare images to tell if one was better than the other or if one was more skewed than the next from 1957 to 1959. Working two jobs while her husband worked three jobs and attended Iowa State, the couple was very poor and had two young children. Living on the then-payment of the G.I. Bill’s $144 a month, the era was an extremely difficult time for Kestel.

“I really don’t remember much about that job — only that I got a paycheck,” Kestel said.

Kestel was contacted and asked if she would be interested in going to Ames and being tested, because the Ames Laboratory was involved at some time with uranium and radiation, and there was some compensation for those that maybe have had health problems.

Kestel hasn’t filed a claim yet, though — she just got the information in the mail and hasn’t read it.

“This just came out of the blue to get this information that I may have a claim,” Kestel said. “I decided to have testing done in Ames, and then decided against it because I thought it was so remote that I would ever have anything that might be related to that.

“But the people involved encouraged me to do that so I did travel to Ames and had this series of tests. And so far, I haven’t received any results from that,” she said.

Kestel had chest X-rays, blood work, a breathing test and urinalysis done in late October.

“I’ve had breast cancer, and I had four miscarriages after I left the lab,” she said. “But how do I know that that had anything to do with it?”

Although there can be unlikely chances of tracing one’s cancer, the secretary’s disfigurement from her mastectomy in 1987 or the chemotherapy that followed it didn’t seem alarming at the time, either.

The woman became convinced that she got breast cancer after being exposed to radiation while working at the Ames Laboratory when she came across an old newsletter from the lab.

The 1960 newsletter reported on activities and unnamed research going on in the buildings and showed pictures of handling of the primitive, unprotected and unsafe equipment that always created leaks and explosions.

“My sister told me, ‘You know you got it from Ames Lab,’ I was in total shock and disbelief.”

She waited two weeks to get surgery and begin chemotherapy. A year after her diagnosis, she found out that her former boss at the lab died of cancer after stumbling across his picture in the obituaries.

The woman called her boss’s widow and was told that her boss’s doctors determined that his cancer was caused by radiation.

In 1985, 21 years after leaving the lab to give birth and only a few years before learning of her own disease, the secretary’s son was diagnosed with thyroid cancer. Pregnant before she left the lab in 1961, the woman wasn’t aware that she had exposed her unborn son to radiation while working at the lab.

With a scar on his neck and another stretching from ear-to-ear, the woman found out there was no claim for her son because he wasn’t employed by the company during that time period.

“That was really sad to happen because of me,” she said.

While working at a local clinic, the formerly lab-employed woman ran into coworkers of the lab.

Each had 1 of the 22 types of cancers and discussed with the woman how there must be a link between the things that went on behind closed doors at the laboratory and their health.

Convinced that there was some sort of correlation, the woman pursued a compensational claim in January 2007, but was turned down because her radiation count was too low.

Radiation must equal up to 50 percent in order to qualify for compensation, according to the National Institute for Occupation Safety and Health.

The woman went through a rigorous claims process with NIOSH including a 17-page testimony, large amounts of documentation and filling out numerous forms.

Later it was determined exposure during these years did occur, and she should receive a one-time lump compensational sum because of her employment that resulted in her illness from the Ames Lab.

NIOSH gave the claim to the advisory board and determined it was a valid exposure and was later approved by Health and Human Services.

After being approved, the claim went to Congress and was approved Friday.

After reading an article in another publication about the lab, the woman read that all former workers should contact Laurence Fuortes of the University of Iowa. Fuortes is the designated person to contact between former workers at the Ames Lab and the Department of Labor.

His main role is to identity people who are candidates for the program, said Alex King, Director of the Ames Laboratory.

“The lab’s position right now is that everybody who was exposed to any harmful chemicals while they worked at the lab is deserving of compensation,” King said. “The work they did to help the defense of the nation and like anybody else who has worked for the U.S. people, they deserve to be taken care of. We hold back nothing from any of those people in terms of helping them establish their case.”

The secretary urged former workers were employed at the Ames Lab from 1955 to 1960 to file the claim if they’ve had cancer no matter if they think it’s related or not. Researching on the Internet and other media for the past four years seems endless according to her and she says that when one waits, things can get very tiring.

“I’m just glad it’s finally over,” she said. “As far as the claims process goes, I can put it behind me and move on. I enjoyed working there and my work, and I’m just sorry that I was exposed and had to go through what I did.”

The secretary didn’t find out what was going on in her building until she got her surgery and began doing extensive research on the internet.

“We knew we couldn’t know of what went on beyond,” she said. “I mean, they were working in the same building I was in, but we couldn’t have known what they were actually doing … they were just down the hall.”