Social media users trade privacy for personalized content

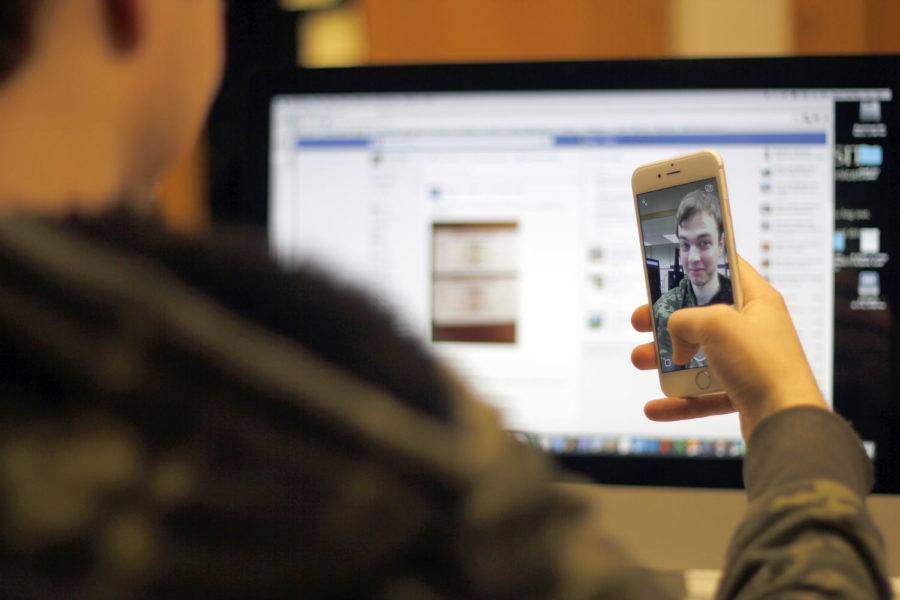

When social media puts pressure on people to look and act certain ways, it can alter perceptions of how people view themselves.

April 29, 2019

Personalization has often been a defining feature of the Internet and, by extension, social media. However, consumers aren’t always aware of what they are giving up to receive these personalized experiences and what is being pushed on them as a result.

Personalized content is often hailed as a defining feature for many services, such as Netflix, YouTube, Spotify, and even advertisements on some of these services.

Spotify releases personalized playlists and “Daily Mix” ‘radio’ stations for its users based on what its algorithm thinks you would enjoy. The Daily Mix stations are usually broken down into six stations that each have their own theme. For example, someone who listens to a lot of 1990s alternative may get a mix of stations based around The Cranberries, Nirvana and other related artists.

YouTube analyzes a user’s watch history and tries to recommend similar videos, channels, and topics that users may be interested in based on their watching habits.

Netflix, Hulu and other streaming services also use the YouTube model, although not to the same extent.

Social media also pushes recommended content onto its users. Facebook feeds may contain the phrase “posts similar to ones you have viewed recently” that pop up like advertisements on news feeds.

Algorithms dominate social media and entertainment platforms and and uses the data it receives from its users and non-users tied to them to provide users with a “personalized experience.”

What are consumers giving up for these personalized experiences? Their own private data, or at least it seems that way.

Facebook has seen the most public criticism for its mishandling of private data and the extent to which it collects and receives that data from users and non-users with ties to them.

They are not alone, however. While players in the industry are often secretive about their practices and what they collect, there is some information available through the work of journalists and from the information obtained from public cases.

Largely due to the Cambridge Analytica scandal in 2018, the extent of the data which Facebook collects has been shown. This includes the sharing of information between Facebook and 150 other companies, such as Amazon and Apple, which Facebook has claimed to have ceased doing since, according to an article from the New York Times.

People can also download their own data that Facebook and Google have about them, and one New York Times journalist, Brian X. Chen, did just this in April 2018 and went through his findings.

The most obvious and “creepy” use of consumer’s private data comes from advertisements. A person may have observed or remarked on an ad that seemed as if it were a little too “targeted.”

For example, receiving an email about glasses, and talking to your friend about their new glasses, and then receiving 50 or more glasses ads on Facebook within a week.

Consumers have taken notice to this personalized ad experience and sometimes it can bother them if done poorly, according to WIRED.

On the same day as Chen’s article in the New York Times, Keith Collins and Kevin Buchanan, also journalists for the Times, explored the history of Facebook’s use of ads and how they came to target consumers.

According to their article, starting in 2014, Facebook started using users’ browser histories in their personalized ad program. The article also states that Facebook can even try and guess its users ethnicities.

Michael Bugeja, a journalism professor, called Facebook the biggest violator of online privacy.

“In 2012, Facebook surpassed 1 billion users,” Bugeja said. “Now it commands 22 percent of the world’s population. That’s a lot of data on users, and as we have seen in the Cambridge Analytica scandal, it can influence elections.”

The data being collected and those collecting it can be shocking. Consumers have questioned the value of the personalized content relative to their sacrifices in privacy, but Bugeja said companies believe it’s worth it.

“Consumer narratives are currency, and they have value,” said Bugeja.

“If, for instance, you say on Twitter, it was cold in Iowa in April and I had to borrow an electric blanket, you will see advertisements for electric blankets. That’s how quickly data is mined when we use these supposedly free social apps,” Bugeja said.

There are ways to limit the amount of data mined from these platforms, however, they are opt-out options, and many users may not know about them unless they go searching for them.

“There’s little you can do since applications moved from desktop to the cloud,” Bugeja said. “Should we get over it? Perhaps. I look at it this way. Be careful what you say and to whom you say it because anything on social media can go viral at any time.”

Bugeja also said that it is important that students, especially those in middle school, learn media and technology literacy.

“Students learn about the dangers of social media by trial and error from Middle School on, allowing all manner of people bully [sic] or abuse their privacy,” Bugeja said.