FREDERICK: Why we must get it right

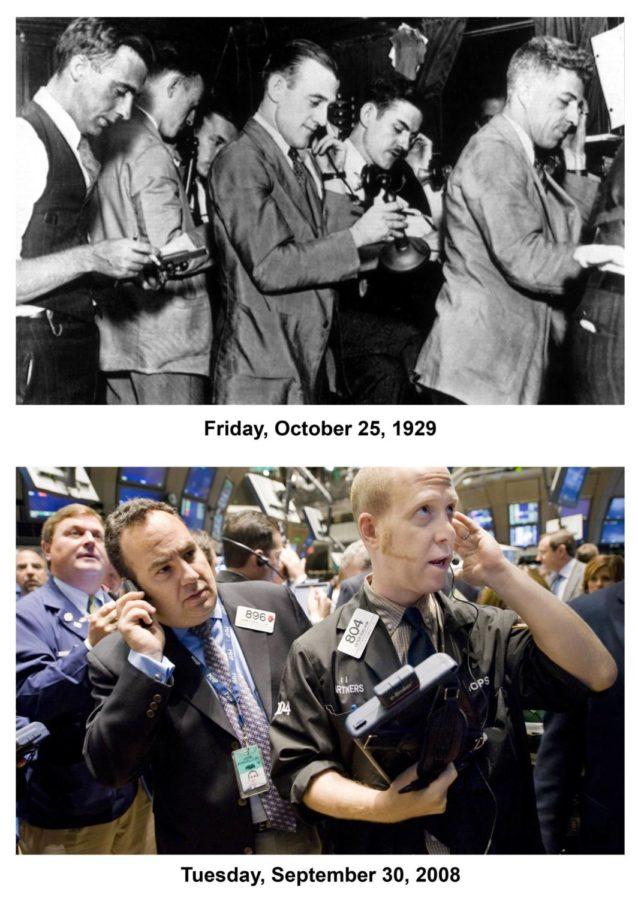

In this photo combo, stock brokers are seen at the New York Stock Exchange on October 25, 1929, one day after “Black Thursday,” the first in a series of crashes which led to the Wall Street Crash of 1929, top; and traders John Porcelli Jr., center, and Peter Edelson, right, work on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange, Tuesday Sept. 30, 2008, one day after the the Dow Jones industrial average lost 777 points, its biggest single-day fall ever. (AP Photos/bottom photo by Richard Drew)

September 29, 2008

The dates of stock market crashes seldom stick in the memory. Indeed, Oct. 29, 1929 just doesn’t quite roll off of the mind like Dec. 7, 1941. Neither does Oct. 19, 1987. Monday will likely be another of those dates, overshadowed by another day in September seven years before, or — who knows — by another date in the future.

Monday’s record point drop on Wall Street was, indeed, dramatic — a massive bailout bill rapidly failing in the House; markets dropping like rain from the sky; Treasury bills quickly becoming the security, not of choice but, rather, of necessity.

While much of the blame — if there needs to be blame attached — for the failure of Bailout Bill 1.0 has to lie at Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s feet after her partisan diatribe from the House floor, there’s more to the story than that. Ninety-five Democrats went across party lines and joined rank-and-file Republicans to vote against this bill for a reason: It is vitally important to get this right, or at least as right as possible.

Granted, “getting this right” is something that no one’s quite sure how to do at this point. The question has to be asked, however, what good $700 billion was ultimately going to do. Printing $700 billion feeds inflation, especially with regard to oil prices. Indeed, crude oil fell $10 on the news of the bailout bill’s failure. Where would we be in a few months if the bailout package didn’t work, and inflation had only spiraled further out of control?

In short, the American economy has a disease. We’ve seen the symptoms: falling housing prices, foreclosing mortgages, increasing borrowing rates and a strikingly sudden gelling of money movement within the economy, among others. What we don’t know, for sure or for certain, is just how extensive the sickness is, or where it’s headed next.

Imagine being sick, going to the pharmacy, and taking random prescription medications, without any regard for their effects or drug interactions. That’s what the bill that the House rejected Monday would have most likely been: a prescription done in a hurry without consideration of alternatives, with a real possibility of causing further harm.

Now, with the patient sedated by anticipation of a rescue package of some kind, the surgeons — Henry Paulson, Ben Bernanke, President Bush, Nancy Pelosi and others — have begun arguing whilst armed with scalpels. Watching Treasury Secretary Paulson work the halls of the Capitol this last week, one can almost envision a doctor working vainly to save a patient slowly bleeding on the table.

One of the major issues that led to Monday’s dramatic reversal was just how much control the lead surgeon, Paulson, should be allowed to exert on the operation. One of the characteristics that has sort of set America apart throughout the vast majority of its existence was its separation of its political capitol — Washington — and its financial “capitol” — New York. This system seems to have worked quite well for the last, well, 200 years or so. While Wall Street has the occasional breakdown or impasse, Washington is almost known for their ability to get nothing done, and to bungle the things they do accomplish.

Handing over the reins of the financial system to the treasury secretary was almost certainly a deal breaker Monday, as well it should have been. From Newsweek’s cover, granting Paulson the sobriquet “King Henry,” to one representative’s remarks likening the power grab to the Bolshevik Revolution, these provisions of the failed bailout bill seemed to be almost universally unpopular.

That wasn’t all that there was to dislike in Monday’s bill, however.

$700 billion.

By any measure, that’s still a lot of money, even in an age that sees $10 billion-a-month wars. The only other figure out there of any use, for comparative purposes, is the federal budget. The bailout package amounted to more money than the federal government spent on social security, both Medicare and Medicaid, or defense in 2007. It’s more than two-and-a-half times the interest that was paid on the national debt that year, as well. In fact, it would have constituted more than a quarter of last year’s federal budget in total.

What’s more — and what irritated House Republicans and Democrats alike — there exist alternatives to this plan that were never considered. Many prominent economists have expressed a number of alternative plans — most of which are at least marginally cheaper — including Simon Johnson, former chief economist at the International Monetary Fund, former Treasury Secretary Paul O’Neill and former FDIC chairman William Isaac.

So no, Monday’s bailout rejection isn’t the end of the world, although the massive slide on Wall Street and the shrinking of the three-month Treasury yield to near zero made it seem that way for a while. In fact, it might be argued, the defeat of the bailout bill was possibly a good thing. While it may not have necessarily been a bad bill, it definitely wasn’t a good one, either. Time for round two. Cross your fingers.

— Ryan Frederick is a senior in management from Orient.