Presidential candidates revive electoral college debate

March 28, 2019

Since campaigning for the 2020 presidential race has begun, an old debate has been revived: should the United States continue using the electoral college system?

Democratic presidential candidate Elizabeth Warren spoke out against the United States’ voting system, known as the electoral college, March 18 at a town hall event. One day later, her fellow primary challenger Robert Francis “Beto” O’Rourke said there was “a lot of wisdom” in what Warren had to say.

Their comments came as part of an argument that David Andersen, an assistant professor of political science, says happens every election season.

Ever since it was put into the Constitution, people have debated whether or not the electoral college should exist. Now that Democratic presidential candidates have brought the issue up on the campaign trail, the argument has broken out again.

Some members of the Iowa State political science department say doing away with the system could negatively affect Iowa’s significance on the national scale while changing the way people campaign.

Mack Shelley, the department chair, said the electoral college could be a difficult system to abolish, describing it as “baked into the Constitution.”

The system operates by having electors from each state vote to appoint a new president. Electors are chosen by state parties and almost always vote according to the state’s outcome. Although, there have been 167 electors throughout American history who have defected, including a record-setting 10 in the 2016 presidential election when the electoral college elected President Donald Trump, despite Hillary Clinton winning the popular vote.

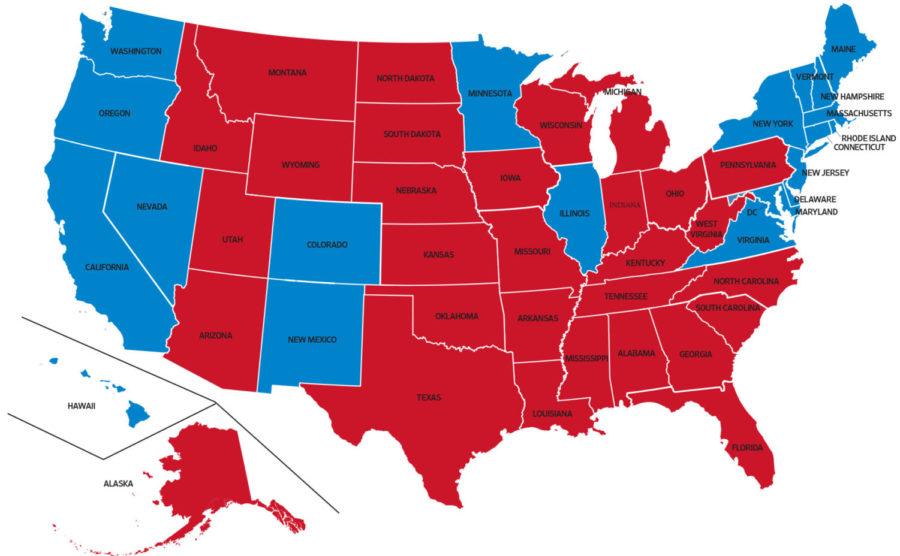

The amount of electors for each state is based on how many representatives each individual state has in Congress. This means every state is guaranteed at least three electoral college votes, with more populated states getting more electors. In 48 of the 50 states, the candidate who wins a plurality of votes is counted as winning the entire state.

Shelley argued that this system is anti-democratic because to win an election, candidates don’t have to receive the most votes, they just have to win the right states up to 270 electoral votes.

As of now, at least 11 states have joined what is called the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact, supporting an alternative to the current system. Shelley said he thinks this measure could face legal issues and probably would not be ready by the 2020 election.

When asked about the effects of keeping and getting rid of the Electoral College, Andersen indicated there could be conflicting interests at stake. He said his position is that the electoral college helps less populated states remain significant in presidential elections.

“If we don’t keep it, nobody will ever come to rural America ever again,” Andersen said.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, Iowa was estimated to have a population of 3.15 million people as of July 1, 2018. In contrast, Los Angeles, California had a population of four million people in 2017. Andersen said under a popular vote system, candidates would be incentivized to head to large cities instead of rural states to garner votes.

Nevertheless, Andersen agreed the Electoral College was not his ideal system but also said a direct popular vote would not work, saying that a new system of districts might serve the purpose better.

“There’s lots of different alternatives we could look at if we really wanted to care about democracy and fairness,” Andersen said.

Andersen and Shelley both said the conversation is being driven by Democrats that are unhappy about losing several elections where they won the popular vote and that doing away with the Electoral College could shift the country in favor of the Democratic party.