Planting seeds

April 27, 2004

ANKENY — Five generations have lived, laughed and cried in the house that Doris Griffieon called home.

Doris’ great-great-great-grandfather owned the land near Ankeny where the house and farm have been built. The gray-haired, soft-spoken woman sits at the wooden kitchen table in the remodeled farmhouse watching her granddaughter and daughter-in-law speak about the farm she has known and loved since she was born.

Autumn Griffieon, junior in agricultural studies, sits next to her grandmother at the table. To Autumn’s right is her mother, LaVon Griffieon, who is the fourth generation to raise a family in the house on the family’s Polk County land.

As the three women discuss their farm, they reflect on the trials and tribulations of being women in rural Iowa.

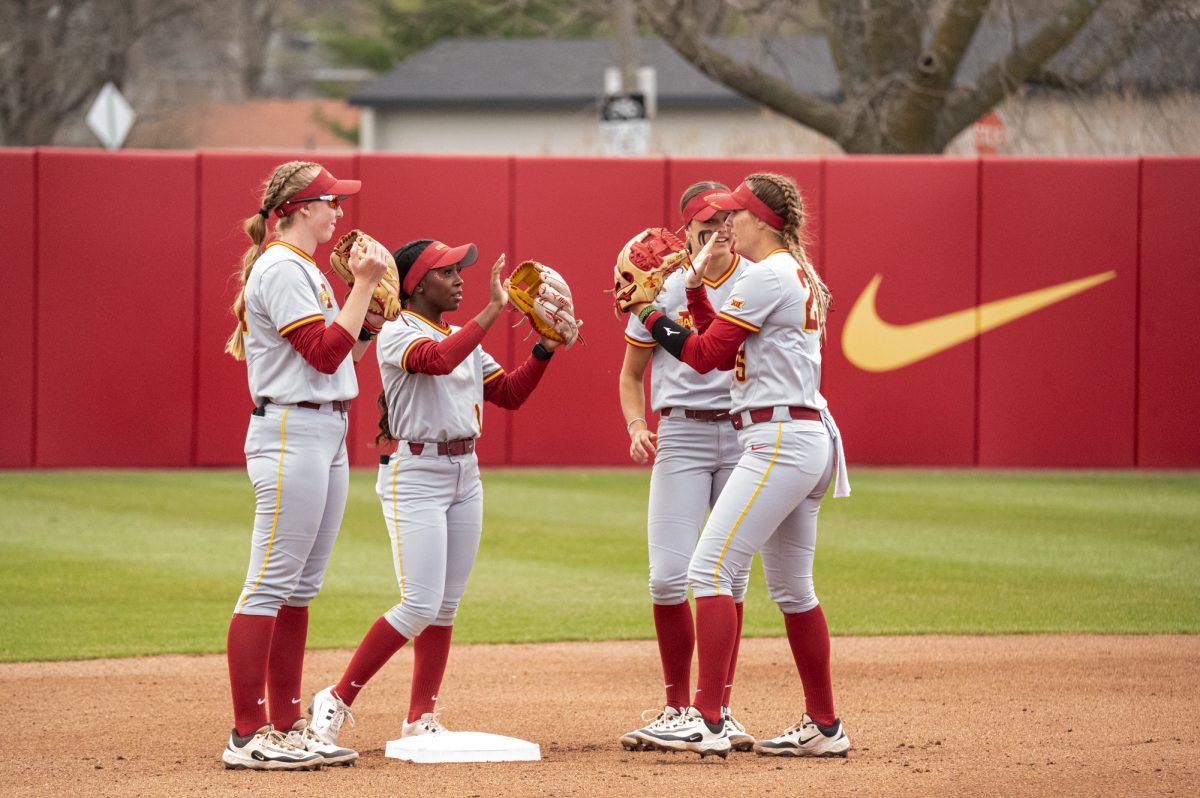

The Griffieon women, like other women in Iowa and at Iowa State, have seen the roles of women in agriculture change, from the difficult choice between returning to the family farm or being a woman in the agriculture industry. Now more than ever, women are trying to define their futures in agriculture.

Autumn, like the other 1,386 women in the College of Agriculture, has many opportunities in agriculture after graduation. As opposed to when her grandmother was farming, she now has almost all the same career options as a man.

But Doris’ granddaughter wants to continue on her family’s farm, a task fewer Iowa women under the age of 25 are undertaking. The 2000 census indicated about 1.3 percent of farmers are women, and most of those are over age 75.

The decision to continue working on the family’s corn, soybean, beef and poultry farm was not a recent one for Autumn. At a young age, Autumn told LaVon she was going to build her own house in the family’s lawn to be close to her family.

But knowing she wanted to return to the farm couldn’t have helped her foresee a major obstacle on her path to the land.

On the farm

In December, Autumn and her family learned the city of Ankeny had created and passed a land development and annexation plan that would consume most of the Griffieon’s farm in the next five to 10 years. The rest of the land will be taken over by 2024.

“It [has] become a threat to my whole future. Why the heck should they eat my farm? What gives them the right?” Autumn said.

Her grandmother said she did not see the plan coming either.

“I just never dreamed of such a thing. You live here all your life, and you think it’s where your kids are going to stay,” Doris said.

“I guess you just don’t think ahead to think they’re ever going to leave.”

The land the family owns is worth $28,000 an acre, Autumn said. One student told her the 820 acres could make her a millionaire — $22.96 million, to be exact.

But the family refuses to sell the land. And Autumn won’t sell either.

“Yeah, I could be a millionaire and live anywhere in the world, but that’s not the kind of life or the quality of life that I want,” she said. “It would uproot me.”

When Autumn graduates and returns to the farm as a primary operator, her situation will be unusual compared to her classmates.

“Of the students who graduate from the College of Agriculture, about 15 percent go back to either the family farm or some type of farming production,” said Mike Gaul, director of career placement for Agriculture Career Services. “That percentage is mostly male.”

Usually, if a woman is helping operate a farm, she works full-time off of the farm and then comes home and helps on the farm after work, Gaul said.

Those women who do not return to the farm find jobs in the industry, Gaul said.

“Honestly, the demand for women in agribusiness right now is enormously high,” Gaul said.

Those opportunities steer many women away from the farm, where they would probably make less money, Gaul said.

And off the farm

Unlike Autumn, Morgan Muhlenbruch, graduate student in agricultural education and studies, is away from the farm and pursuing her master’s degree. She wants to work in the industry as a teacher of agriculture. However, she said she hopes to return to a farm one day. Despite deciding not to farm, she and Autumn have one thing in common — both are women passionate about agriculture.

“I love agriculture, and that’s why I want to go into teaching it,” Muhlenbruch said.

She said her family is a big reason to remain involved in farming. She is the oldest of three daughters born and raised on a livestock and grain farm near Dows. Farming is in her blood.

Someday her family, like many others in Iowa, will have to ask if the farm that has been their lives will stay in the family when Muhlenbruch’s father is finished farming.

“My dad doesn’t have anybody to pass the farm on to. I’m definitely the most likely to go back into production agriculture,” Muhlenbruch said.

“I’ll have a few cows no matter what.”

Her determination to stay involved in agriculture spills over into the job market.

“Typically in ag, guys don’t see women as competent, being able to do it. They say, ‘Oh, you’re a girl, what can you know about farming or about agriculture?'” she said.

“I think my experiences will get me that job. Book smarts are part, but practical experiences are part too.”

Those book smarts have been encouraged by professors though, she said.

“Professors here at Iowa State don’t see the gender lines as much as they maybe used to,” Muhlenbruch said.

High demand

Michael Kenealy, professor of animal science, said he has taken a survey of his students every semester since he began at Iowa State. He said the number of women enrolled in his classes has increased dramatically in the last 15 years.

In 1989, 39 percent of his students were female. Last fall, 68 percent of his students were women, he said.

Kenealy said women may have felt denied opportunities in the agriculture industry 25 years ago when he started at Iowa State. Since then, he said he has seen women taking advantage of more and more opportunities.

“It’s a real competitive spirit brought on by thinking they might be behind. The average female student seems to be more competitive and motivated for success [than the typical male student],” he said.

The ratio of women to men is higher for College of Agriculture students than faculty and staff, Kenealy said.

He said he has been impressed with the leadership at Iowa State, Kenealy said.

“For a while, all of my bosses were female,” Kenealy said. “My interim department head was a woman, the dean [of the College of Agriculture] is a woman, the Iowa Secretary of Agriculture is a woman and the U.S. Secretary of Agriculture is a woman.”

Kenealy said these women act as positive role models for females in the College of Agriculture to pursue higher education.

Catherine Woteki, dean of the College of Agriculture, said she has seen a steady progress for women in agriculture. She said women have done fairly well in terms of equality compared to the progress made by other groups.

“I think part of it,” she said, “is the removing of the perceived barriers to employment.”