Ziemann: You, me and the GRE

July 29, 2020

Editor’s Note: This is the second of two columns concerning graduate school conducted by Megan Ziemann.

I want to go to graduate school. I’m not sure when or how or where, but I want to. Last week I talked about my journey with grad school and how my past as a gifted kid affected my desire to go.

This week, let’s talk about actually going. Rather, let’s talk about why it’s so hard to go.

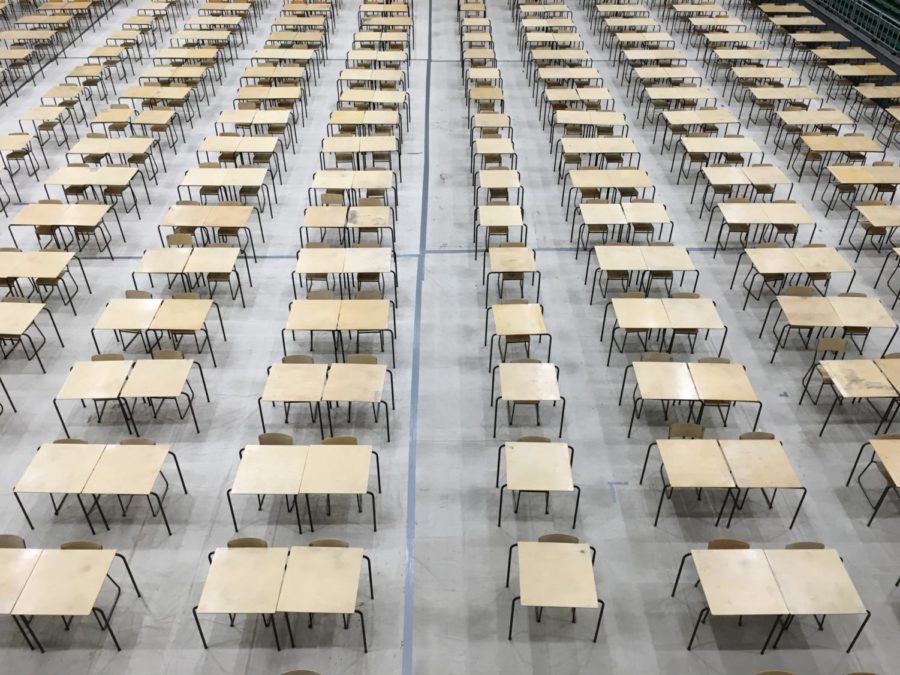

If you’re planning on attending grad school in the near future, chances are you’re going to be taking the Graduate Record Examination (GRE). Created in 1949, the GRE was designed to measure skills like verbal and quantitative reasoning and analytical writing. The three-and-a-half to four-hour-long test is meant to be a benchmark assessment so graduate schools can better understand the potential incoming cohort of students.

You can take the exam any time of the year at a GRE-specific testing center. The exam costs $205, and GRE preparation experts also recommend purchasing review books or even entire review courses that focus on each of the sections of the exam. But, hey, at least the practice test is free!

The GRE is one of many graduate school assessments a student can elect to take. For example, I’m a business student, so if I wanted to get my Masters in Business Administration (MBA), I could take the GRE or the Graduate Management Admission Test (GMAT).

Depending on the application, your GRE, GMAT or other test score can make or break your graduate school prospects.

Which would be great if the GRE accurately measured students’ intelligence and readiness for graduate school.

Instead, it fails to predict student success, and if it does, it only applies to that student’s first year of grad school. The test is centered around analytical thinking, which does account for some student success, but it does not measure concrete skills actually needed for the jobs students will have after graduate school.

If anything, the test is an indicator of the students’ socioeconomic background, race and gender. Black students, Indigenous students and students of color are massively underrepresented in graduate cohorts, and the GRE is partly to blame. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, only 8 percent of Black students and 5 percent of Hispanic or Latinx students have some form of an advanced degree. Taking the GRE takes money, time, labor and confidence — all things significantly easier for white people, men and other privileged groups to have.

It feels like I write this in every column, but racism, sexism and classism are systemic, and until the system is changed, people from marginalized communities will continue to be marginalized in multiple ways. The GRE and other grad school entrance exams are no exception.

A couple of weeks ago, one of my friends from high school voiced her difficulties on Twitter about taking the test due to COVID-19 related closures. “Amazing that I registered for the GRE test back in February and I have not received one email from them since then,” she wrote. “I’ve tried to phone my test center multiple times to see if they’re open and I go straight to voicemail every time.”

My friend is entering her senior year at her university, just like I am. If she wants to go to graduate school right after undergrad, she’s running out of time to take the GRE. So far, she has received no help, no guidance and no contact with her testing center.

If this is how GRE testing centers handle COVID-19, I am not surprised so many marginalized students don’t take the test at all. The test is expensive, long, aimed at privileged students and your results aren’t guaranteed to get you into any school.

Even if you’re extremely qualified for a grad program and it’s your dream to have that second diploma, that dream is just not attainable for a lot of marginalized students. If you’re having to take out more loans, potentially move away from your family and not support them as much as you did in undergrad, why consider shelling out another $205 to take an exam?

Test fees are racist, sexist and most of all classist and should not be a normal part of getting an advanced degree.

Another friend of mine told me about their struggles with deciding whether to attend a grad program.

“I’m queer, I’m genderqueer, I’m an immigrant and I’m a person of color,” they said. “Higher education wasn’t made to serve the identities I hold.”

They are considering law school, a field already known to be classist and sexist.

“I wanted to go into criminal prosecution,” they told me, “because I saw that the criminal justice system does not serve or advocate for survivors and victims. It gets increasingly harder every day to justify going into a field that is not, and was never, designed to help people like me.”

As a cisgender, straight white person who comes from an average financial background, I don’t have to worry about most of the things my BIPOC, LGBTQIA+ and low-income friends do. Sure, paying $205 to take a test is going to hurt, but it won’t prevent me from paying my rent or eating. Most of the time, my voice will be heard by my classmates and professors. Higher education is made to serve me.

Test fees are just another barrier for low-income, first-generation and otherwise marginalized students. Test fees keep poor people poor.

The GRE does offer a fee reduction program that allows students who have demonstrated financial need to pay half the price of the original fee. However, there are a limited number of these fee reduction vouchers, and the burden is on the student to prove their financial hardship.

To me, that’s not enough. The test should be free.

Creating a change like this is hard, but privileged voices carry the words marginalized ones have been screaming for decades. If this is an issue you’re passionate about, take time to write to or call your legislators. Contact the organization that administers the GRE and voice your opinions. There is still so much we can do.

It’s time for us to step up and break down systemic barriers to graduate school.

Because everyone who wants a degree should have the chance to get one.