Hellman: An ex-gymnast’s perspective on “Athlete A”

June 29, 2020

For 15 years, the sport of gymnastics dominated my life. I spent the same — if not more — time with my teammates and coaches than with my siblings and parents. I excelled as a child and found my way onto the Junior Olympic team (JO) at a young age. Naturally, I was very comfortable in the gym, practically having grown up there. I didn’t enjoy every practice, but that was very rarely due to the treatment from my coaches. More often than not, it was simply because gymnastics truly challenged me beyond my mental and physical limits. I had my boundaries and priorities, which were shared and upheld by my supportive coaches and teammates.

For elite gymnasts, there is no such thing as boundaries or limitations. They work through anything and everything, no matter the physical, mental or emotional pain. My understanding of this was confirmed by “Athlete A’s” explanation of the tragic inhumanity that is depicted as heroism by Marta and Bela Karolyi.

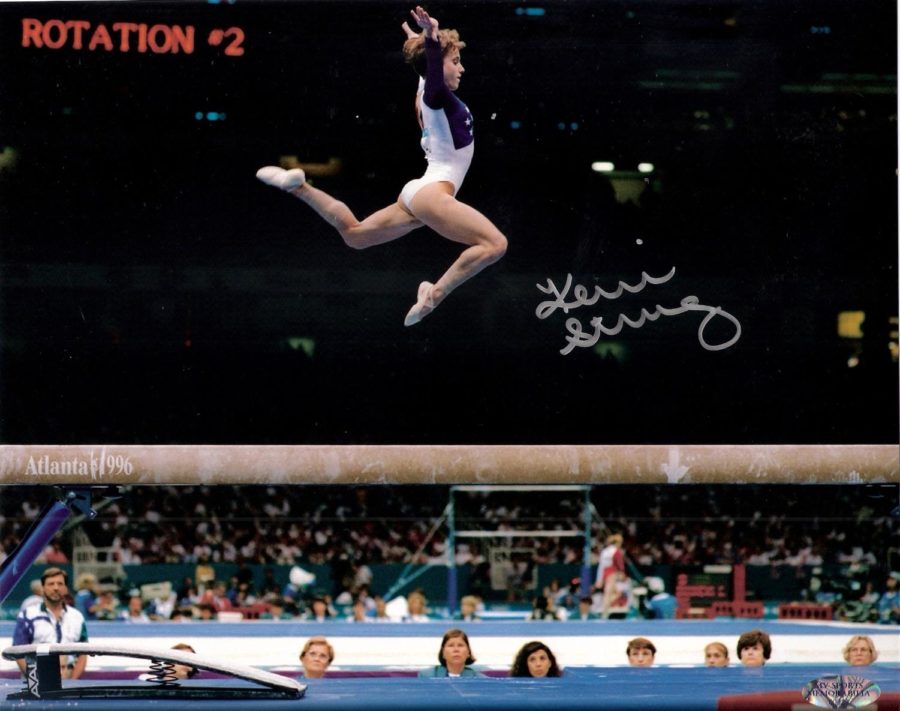

As a gymnast, I aspired to be as strong as Kerri Strug, who secured the gold for the U.S. Women’s Gymnastics Team in the 1996 Olympics after vaulting on a severely injured ankle. Bela Karolyi was viewed as her savior, carrying her off the mats like a hero. It was every gymnast’s understanding that Strug was strong enough to put her teammates and her own aspirations for success before her physical pain. “Athlete A” made it clear it was never her decision in the first place.

The elite coaches at my gym were supportive, but expected to put gymnastics before the gymnast. That’s not to say they didn’t care about the girls, but I think they felt pressured to create perfect athletes by everyone — competing gyms, judges, parents, USA Gymnastics (USAG), even us.

USAG created the image and reality of elite gymnasts using detrimental and inhumane tactics, specifically at The Ranch (the Karolyi’s USAG training center in the middle of nowhere Texas), where elites would train every month. “Athlete A” goes into depth on the Karolyi’s methods of gymnastics training, which was largely abusive and inhumane.

“Athlete A” brought to light the horrifying truth that Larry Nassar, while incredibly damaging to these gymnasts, was only one part of the conflict within USAG. He used USAG’s inhumane coaching and managing system to sexually assault over 500 girls. Knowing profit and success were valued over the gymnasts themselves, he was able to operate these disgusting acts under the protection of USAG.

After watching this documentary, it was clearer than ever why my friends who trained at The Ranch every month never seemed to be excited to go to Texas. I excused it as fatigue from constant training, but now I see The Ranch’s gym was no home to them, as my gym was to me. I do not know what they personally experienced there, but I do know it was a place of brutality and manipulation. Unfortunately, this won America gold medal after gold medal, which encouraged several coaches to implement similar coaching styles in their own gyms.

My coaches will forever be my role models, and I remain extremely grateful for the empathy and understanding they treated our JO team with. However, my coaches did not go to the Karolyi Ranch every month, whereas the elite coaches did.

Occasionally I saw or experienced hurtful techniques from the elite coaches. In one instance, my team and I were humiliated when our coach (who at the time coached JO, but soon switched to elite) pointed at the strongest and leanest girl in the gym and insisted we needed to look like her and train as hard as her to be successful. We were around the age of 11, while she was around 16. Before then, I don’t remember having negative thoughts about my body. After that, the ambition to lose weight never left my mind.

Obviously, gymnastics is a tough sport. Coaches must prioritize gymnasts without putting their dreams of success on hold. When injuries arise, is it challenging to decide how much pain is too much, especially for an elite gymnast with Olympic-size ambitions. As a coach myself, I struggle every practice between “babying” the gymnasts or working them too hard. USAG staff, however, disguised their abusive actions as tough love and hardened gymnasts by continuously crossing the line from overworking to abusing.

“Athlete A” should be congratulated for exposing the inhumanity within USAG staff, while never taking the focus off the survivors. I believe this documentary allows gyms and coaches to take a deeper look at the truth behind gymnastics’ idols, such as Nadia Comaneci, Kerri Strug and, more recently, Maggie Nichols. USAG exploited and capitalized on their strength, resiliency and love for gymnastics to win gold medals and sponsorships, while disregarding their health and safety.

It is my hope that coaches and gymnasts everywhere watch “Athlete A” and reflect upon the history of abuse in gymnastics and the possible applications within their own gym. This is necessary to ensure gymnastics reestablishes its roots of shaping gymnasts into young women worthy of more than gold medals.