How COVID-19 compares to the last major pandemic

March 22, 2020

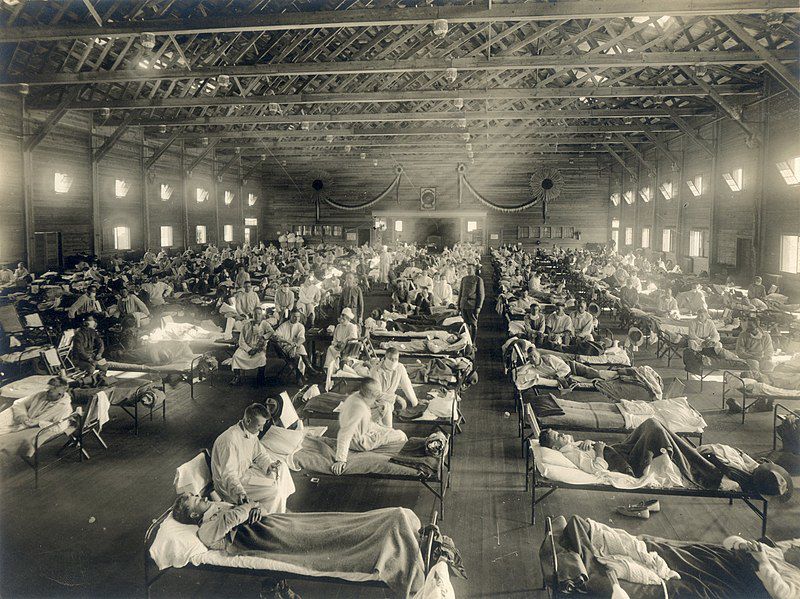

In 1918, a deadly strain of the H1N1 influenza virus swept across the world, killing millions of people.

This pandemic became known as the Spanish flu, in part due to Spain’s neutrality in World War I and a lack of wartime censors that in the belligerent powers prevented reporting on how much the disease had spread throughout their countries, according to History.com, and it is considered the most deadly pandemic in recent history.

In the 102 years since then, there have been four major pandemics as defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) — the 1957 H2N2 virus, the 1968 H3N2 virus, and the 2009 H1N1 virus. Now a new disease is spreading across the world, named COVID-19.

COVID-19 is a respiratory illness caused by a novel coronavirus. While the mortality rate of COVID-19 is not yet known for sure, the CDC has estimated that the mortality rate could be up to 12 percent in disease hotspots and around 1 percent in more mildly affected areas. The Spanish flu had a mortality rate of approximately 2.5 percent and was estimated to have killed at least 50 million people globally, according to the CDC.

The current pandemic has elicited a response from state and federal governments, and from the public. Grocery stores across the country have been emptied with lines lining up around the block. States are issuing “stay-at-home” orders and both the northern and southern borders have been closed to nonessential travel. People are being encouraged to practice “social distancing” and avoid gathering in groups of any size.

Gov. Kim Reynolds has recommended schools close for four weeks and Iowa State has moved to finish classes after spring break with entirely online instruction.

Amy Bix, professor of history at Iowa State, said a mass reaction to a pandemic on such a large scale hasn’t been seen since 1918.

“The biggest difference so far seems to be in the patterns of which groups are most vulnerable,” Bix said.

COVID-19 can be dangerous for anyone, but the people considered most at risk are those above the age of 65 and others that have underlying conditions, compromised immune systems or a combination of the two.

“The 1918 flu hit people from eighteen to forty-five years old especially hard,” Bix said. “It may be that older people had previously been exposed to an earlier version that provided them extra immunity. So it was unusual to see the 1918 flu killing younger people who were otherwise generally healthy.”

Another difference is the existence of social media and the ability to spread information quickly and on a large platform.

“This is the first major contagious disease episode of our modern social-media world,” Bix said. “At its best, social media can help provide widespread access to reliable, vital information and social support for those who are quarantined, self-isolated, or alarmed. At its worst, social media risks spreading inaccurate ideas, divisiveness, and conspiracy thinking.”

The economy is also a concern during a pandemic, just as it was in 1918. Businesses had to close because of the pandemic and suffered because of it.

Bix said this economic downturn could be short or could last an indefinite amount of time.

“There may be a relatively short but very painful economic crisis followed by at least a partial rebound once the disease spread is blocked and a vaccine has been developed,” Bix said. “Or the immediate crisis piled on top of pre-existing economic weaknesses […] may lead to more long-lasting economic turmoil.”

The Dow Jones Industrial Average, an American stock index that measures the performance of 30 companies on the stock exchange, has lost more than 35 percent of its value from its pre-crisis Feb. 12 high as of March 20. Many firms, including Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley, have projected the effects of the disease will cause a recession.

Scientists and medical professionals learned from the Spanish flu, and that flu helped give more of an understanding of what to do when it comes to responding to disease pandemics. The world also has a more developed medical system with a higher capacity to respond to diseases.

“In 1918, hospitals didn’t have today’s treatment options and specialized expertise to help the most endangered patients with high-tech intensive care […] they didn’t have anything like modern antiviral treatments or our antibiotics to control the secondary infections such as pneumonia that actually accounted for a good number of the 1918 deaths,” Bix said. “The medical world didn’t have anything like the knowledge that we have today about viruses and their spread, the foundation of prior medical research. The world was able to identify the disease and even sequence its genome very quickly, setting the stage for moving ahead toward vaccine development.”

The issue now is trying to contain the spread and mitigate the worst consequences of the disease while the world works to create, test and distribute a vaccine for COVID-19, Bix said.

“[S]o the immediate challenge is in getting sufficient resources to the right places, ventilators, good testing kits, protective equipment and so forth,” Bix said. “So far, the US response here has left much room for improvement.”

Many states have cited low supply numbers. Throughout the pandemic, the number of tests for the disease that health officials in Iowa have at the State Hygienic Lab has numbered in the hundreds, while other states stockpiles number in the tens of thousands. There are 68 confirmed cases of COVID-19 in the state of Iowa as of March 21, according to the Iowa Department of Public Health.