- Limelight

- Limelight / Culture

- Limelight / Culture / Pop Culture

- Limelight / Visual Media

- Limelight / Visual Media / Film

The history and rise of South Korean cinema

Youngchang Kim

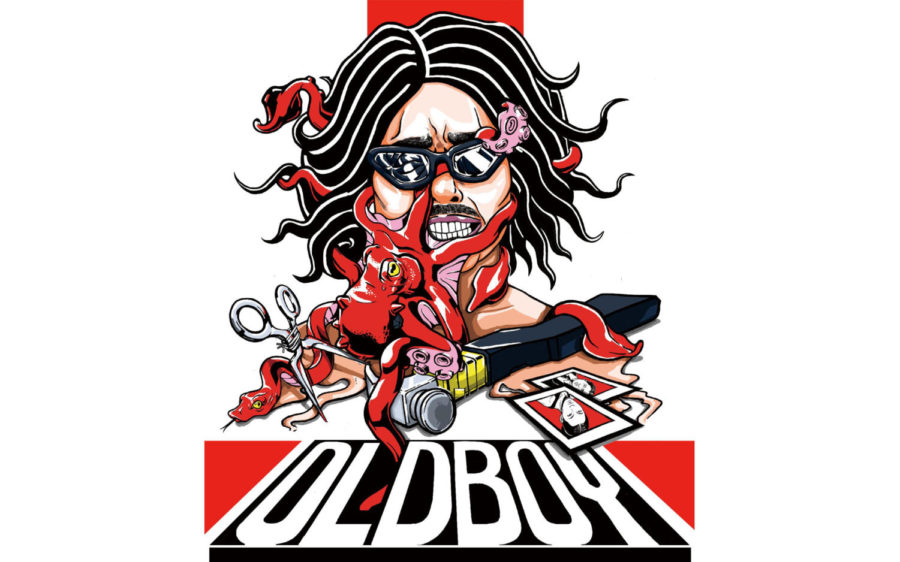

The 2003 film “Oldboy,” directed by Park Chan-wook, is among many films credited for increasing popularity for South Korean films in western markets.

February 26, 2020

Everyone, even President Donald Trump, seems to be talking about South Korean cinema after Palme d’Or-recipient Bong Joon-ho took home four Oscars for his film “Parasite,” including the best picture Oscar — the first non-English language film to do so in the history of the Academy Awards.

That isn’t to say that Korean movies are new, even to Americans. South Korean cinema has arguably been prominent in the West and in the United States for at least two decades.

Barbara Demick, journalist and former Beijing bureau chief of the Los Angeles Times, said in a 2005 article from The Los Angeles Times that “Hollywood considers South Korea to be one of its more lucrative foreign markets,” and “South Koreans typically have a major presence at the American Film Market.”

While “Parasite” brought global attention to the South Korean film industry, movies like 2003 Grand Pix-recipient “Oldboy,” directed by Park Chan-wook, and “Burning,” directed by Lee Chang-dong, which won 101 accolades, have also gained substantial attention in the West.

Korean films are often best known for their themes of revenge, politics and class issues. South Korea also has a long history of political and economic instability and governmental corruption, as it went from extreme military rule to democratization and industrialization in the 20th century, which has been particularly harmful to the working class.

Korean cinema began with Do-san Kim’s “Righteous Revenge” on Oct. 27, 1919. This day is now recognized and celebrated as Korean Film Day. However, the Korean film industry didn’t really take off until the late 1940s after their liberation from Japan in 1945 with movies that depicted and celebrated Korean independence, according to Lee Gyu-lee’s article from The Korea Times.

Shortly after, the then-growing film industry was affected by the Korean War, in which active combat lasted from 1950 to 1953. A total of 14 films were produced during those three years, which have since been lost as the country split into two separate nations.

After the Korean War came to a cease-fire, the South Korean government support and foreign aid helped revive the film industry, which led to South Korea’s “Golden Age of Cinema.” From the mid-1950s to the 1970s, these films consisted mostly of melodramas that often explored class issues.

Kim Ki-young’s “The Housemaid” follows the story of a woman who is hired by an upper-class family to be their servant. It’s a prominent example of the Golden Age of Cinema and is considered by many film critics to be one of the greatest films made in South Korea. The film also reflects political issues relevant to its time.

“The Housemaid” was produced in a time period of “development driven by dictatorship,” in which “[laborers] became an expendable human resource in the industrialization process,” according to Ahn Minhwa’s article from Asianfilms.org.

Filmmakers during this time were subject to censorship and faced getting blacklisted or imprisonment if their work wasn’t loyal to the government, such as film producer and director Shin Sang-ok, who was blacklisted by the South Korean government and then kidnapped by the North Korean government in 1978.

The Golden Age came to an end in the 1970s under Yusin System, also known as the Fourth Republic of Korea, in which South Koreans were under the authoritarian rule of President Park Chung-hee. Censorship laws and governmental control of South Korean media posed a problem for filmmakers and audiences alike. After Chung-hee was assassinated, heavy censorship laws continued under the authoritarian rule of President Chun Doo-hwan.

As South Korea began to industrialize rapidly, governmental control of the media and film industry began to relax in the 1980s. The film industry slowly recovered and began to see international recognition. However, the industry suffered again during the International Monetary Fund (IMF) crisis in 1997 when its global stock markets had a sudden drop. Despite the quickly growing economy, South Korea suffers due to military crises related to North Korea, according to an article from Hankyoreh.

Following the IMF crisis and the persistence of young filmmakers, we are now currently in the “New Korean Cinema” wave. Larger-budget productions and international coproductions now dominate the South Korean film industry and continue to perform strongly, according to Darcy Paquet’s book “New Korean Cinema: Breaking the Waves.”

One of the first huge South Korean blockbusters was Kang Je-gyu’s film “Shiri” (1999), which follows the story of a North Korean spy in Seoul, South Korea. Other notable examples include “My Sassy Girl” (Kwak Jae-yong, 2001), “Taegukgi” (Je-gyu, 2004), “The Host” (Joon-ho, 2006), “Train to Busan” (Yeon Sang-ho, 2016) and, of course, “Parasite.”

Hollywood continues to dominate the global film market, but with the success of “Parasite” in the United States, more films from South Korea and foreign films as a whole may find similar success.