Biden’s $2.3 trillion infrastructure plan will likely provide significant boost to US economy

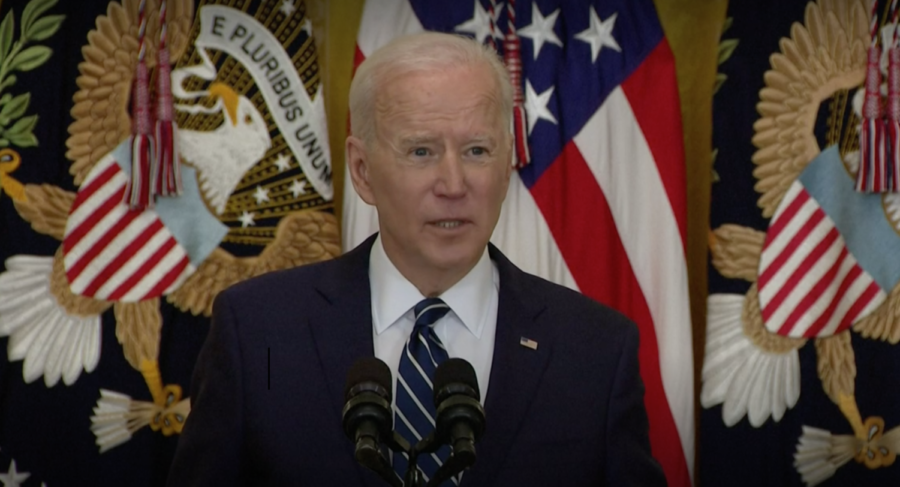

President Joe Biden holds his first press conference after the $1.9 trillion COVID-19 relief package passed.

April 4, 2021

President Joe Biden unveiled his sweeping $2.3 trillion infrastructure plan in a speech in western Pennsylvania on Wednesday afternoon.

The proposal, called the “American Jobs Plan,” would fund improvements in what is traditionally considered infrastructure, such as roads, bridges and water systems, as well as overhauls in green energy, broadband and basic research, among other things. It would also create millions of jobs as these projects are implemented.

“We’re going to create the strongest, most resilient, innovative economy in the world,” Biden said in the speech. “It’s a once-in-a-generation investment in America, unlike anything we’ve seen or done since we built the interstate highway system and the space race decades ago.”

Despite the high price tag, engineers and other technical experts have pleaded for years for the government to invest in repairing and improving the United States’ deteriorating infrastructure. In a report card released in March 2021, the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) gave the country’s infrastructure a C-minus. Iowa’s infrastructure received a C.

Some aspects of the infrastructure are in worse condition than others. The U.S. received a D in the aviation category and a D in the roads category. Iowa earned a D-plus for its bridges.

“No one wants to get a D-plus from a course,” Halil Ceylan, professor of civil engineering at Iowa State University, said. “We do need a lot of investment in our infrastructure.”

The United States’ investment in infrastructure has been dwindling in recent years. A 2019 report by the World Economic Forum listed the United States as 13 out of 141 analyzed countries in the quality of its infrastructure. It scored even lower in terms of road quality, rail density, electricity supply quality and drinking water quality.

Infrastructure directly affects a region or a country’s economic competitiveness as well, Ceylan said. Iowa’s economy relies on being able to move agricultural products to market efficiently, which, Ceylan said, is dependent on roads and bridges.

Ceylan illustrated the underinvestment in infrastructure by pointing to the fact that Iowa’s road engineers often have to make road repair decisions as a function of available financial resources rather than as a function of safety.

“Let’s say they need to put 2 to 4 inches of asphalt [for a safe road repair],” Ceylan said. “But they can only afford that 1 inch because they don’t have enough resources.”

The $2.3 trillion price tag does not just go to financing the repair of roads and bridges however. Some of the key investment items include:

-

$400 billion for home- and community-based care for the elderly and disabled

-

$300 billion invested in domestic manufacturing and business

-

$213 billion to build affordable housing

-

$180 billion for research and development, including $50 billion for climate-specific research

-

$174 billion for electric vehicle infrastructure, including building 500,000 charging stations nationwide

-

$114 billion to modernizing 20,000 miles of roads and 10,000 bridges

-

$101 billion to modernize water infrastructure, including removing lead pipes

-

$100 billion to expand affordable, high-speed broadband nationwide

-

$100 billion to upgrade and “green” the electric grid

-

$100 billion for constructing schools

-

$100 billion in workforce development for underserved communities

-

$85 billion to upgrade existing public transportation

-

$80 billion to update rail infrastructure

-

$50 billion to improve infrastructure resilience

-

$25 billion for airports

-

$10 billion for a Civilian Climate Corps

Approximately 60 percent of costs from the $2.3 trillion will be financed by an increase in the corporate tax rate, with the remainder financed by government borrowing, although the White House estimates the corporate tax increases alone will recover the spending over 15 years.

Corporate tax rates would be increased from 21 percent to 28 percent under the proposal. This new rate is still a historical low, having been reduced from 35 percent by tax cuts during the Trump administration.

The Global Minimum Tax, which taxes profit generated by multinational U.S. corporations who have moved their legal headquarters overseas to countries with lower tax rates, would also be increased from the current rate of 15 percent to 21 percent.

The impacts of the investment would be broad and significant.

“It will benefit the next generations to come, with better investments in broadband, the energy sector, transportation sector,” Ceylan said. “A big portion of this is going to go into the transportation sector, six hundred-some billion.”

While the plan calls for improving 20,000 miles of roads, there are more than 4 million total miles of roadways in the United States. Bringing all of those roads up to an “A-plus” condition by ASCE standards is not doable.

“There’s not enough money in the world,” Ceylan said. “But it’s a good start. We have a lot of deficient bridges and roads that need maintenance and rehabilitation, so that’s why this investment comes with excellent timing.”

While critics have pointed out that infrastructure has traditionally meant roads, bridges, air and seaports, Ceylan praised the inclusion of the electric grid, broadband and other investments in the plan.

Universal broadband, he said, would connect underserved and underrepresented areas, boosting the economy and creating more resilience in events like a pandemic. Ceylan also pointed to Texas, where dramatically cold temperatures overwhelmed energy and utility grids that weren’t prepared to deal with unpredictable events.

“These systems are connected to each other,” Ceylan said. “Our transportation system is going through a paradigm shift. We will be electrifying the road infrastructure systems, we will be electrifying airports and rail systems.”

Better physical infrastructure, along with the other investments proposed by Biden, would provide a significant boost to the economy on multiple fronts.

“You’ll have a directed economic impact from people building more stuff — construction jobs, jobs for material and handling, mining gravel, that kind of stuff,” Peter Orazem, professor of economics at Iowa State, said. “Plus, presumably, you’re going to get a benefit from the improved transit, the cost of transporting goods and passengers should go down.”

Orazem said there is a general consensus among economists that infrastructure investment of the sort proposed by Biden’s plan is overdue, along with evidence that there is support for it among the general public.

The American Jobs Plan also includes subsidies for the purchase of electric vehicles, along with the construction of nearly half a million charging stations throughout the country. Those proposed increased subsidies, along with the returns to scale generated by the federal government’s planned switch to electric vehicles, could potentially lower the cost of electric vehicles, Orazem said, but they will likely remain relatively expensive.

“The electric vehicle ramping up is probably going to be more important for California and the East Coast than it will be for the more rural, less densely populated Midwest,” Orazem said.

Ceylan, however, pointed to the commitments made by some automakers to produce mostly or exclusively electric vehicles by the mid-2030s as an indication that, combined with incentives in the infrastructure plan, could reshape transportation in the United States.

“Twenty years from now, someone coming to Iowa State, if they want to have a car, they may only have one option,” Ceylan said. “And that’s to buy electric.”

Investments in research and development, especially in basic research of the sort that often occurs in universities, would also likely have a positive impact on the economy, although those would likely be long term rather than short-term returns.

“The pace of labor productivity has decreased since 2000 compared to the previous century, and that’s partly blamed on the slowdown in the rate of growth in spending or R&D,” Orazem said. “There are also concerns that China is eclipsing the United States in terms of research and development.”

Orazem said the effects of the infrastructure proposal would likely be limited in Iowa, relative to the effects seen in the more densely populated coastal regions. In terms of manufacturing, Iowa is not a heavy producer of cars or things related to electric vehicles and so would not benefit from increases in use.

Increased investment in wind energy production, as well as greater funding for research at the regents universities, would likely have an impact in the state.

“Some of the infrastructure spendings is ramping up electricity transmission wires,” Orazem said. “There’s a limited demand for electricity in Iowa by itself, and so if we’re going to ramp up wind power dramatically, we have to be able to export that electricity to more populated areas of the Midwest.”

Improved transportation infrastructure would benefit Iowa’s agricultural economy as well, Ceylan said.

“We need a healthy infrastructure so that we can actually get all these products, say the grain and animal products, to the world markets. We can only do that with a well-functioning and healthy transportation infrastructure,” Ceylan said. “If Brazil can take soybeans to the market faster and more affordably than Iowa, Iowa’s economy is going to struggle.”

The interplay between electric vehicles and Iowa’s biofuels industry is raising concerns among Iowa’s congressional representatives about the level of support in the proposal for electric vehicles and the impact that could have on Iowa’s farmers.

Iowa is one of the largest producers of biofuels in the world. According to the Iowa Corn Growers Association, 39 percent of corn grown in Iowa goes to the production of ethanol.

“It’s one of the cleanest forms of energy you have,” U.S. Rep. Randy Feenstra, a Republican representing Iowa’s Fourth Congressional District, said. “If you’re talking about carbon sequestration and helping biofuels and biodiesels, I want to be involved. But when you start saying you want to do it with electric vehicles, I say, what about Iowa? How does this help Iowa?”

Orazem did not echo this concern over the future of ethanol production, citing the increase in hybrid technology in carbon-based vehicles that will lower the future demand for ethanol independent of Biden’s infrastructure plan.

“I think there may be alternative uses of corn and soybeans that are not directly fuel related,” Orazem said.

Chuck Klapatauskas, a junior in mechanical engineering and president of Young Americans for Freedom, expressed concerns over the levels of debt the United States will likely be taking on as part of the plan’s financing.

“The rate at which we print off and spend money, which COVID has accelerated, is bringing us to a point of no return,” Klapatauskas said in an email. “I love the idea of additional infrastructure investments, but that funding cannot be from simply extending the debt ceiling.”

Orazem said that, following the COVID relief packages, the U.S. economy is in uncharted territory for borrowing levels. Although hesitant to make forecasts, he compared borrowing to pay for infrastructure to buying a house, saying it makes sense to borrow for things that are going to have a payoff over multiple years.

“We don’t usually pay cash for a house…because we’re consuming the services of that house over the next 20 or 30 years,” Orazem said. “For capital expenditures, it makes sense for the government to borrow because future people will benefit from those capital expenditures.”

He contrasted this with borrowing for transfer payments — payments from the government to individuals not in exchange for goods or services — such as the recent COVID relief stimulus payments. Borrowing from transfer payments risks causing spikes in inflation, or a sustained rise in price levels over time.

“The scary thing about the stimulus package is that it’s largely going to transfer payments and not production capacity,” Orazem said. “If people start wanting to spend that money all at once, and we haven’t increased the amount of things to buy, basically it’s going to [lead to] too many dollars chasing too few goods.”

Despite the large price tag and longtime horizon, Orazem and Ceylan were both optimistic about the impact that such an investment would have on the U.S. in the long run.

“I actually would like to make a comparison to President Kennedy,” Ceylan said. “When he said that we were going to land a man on the moon by the end of the decade…so many of the advancements, like in microcomputers, that we all use today, happened because of that big visionary goal.”